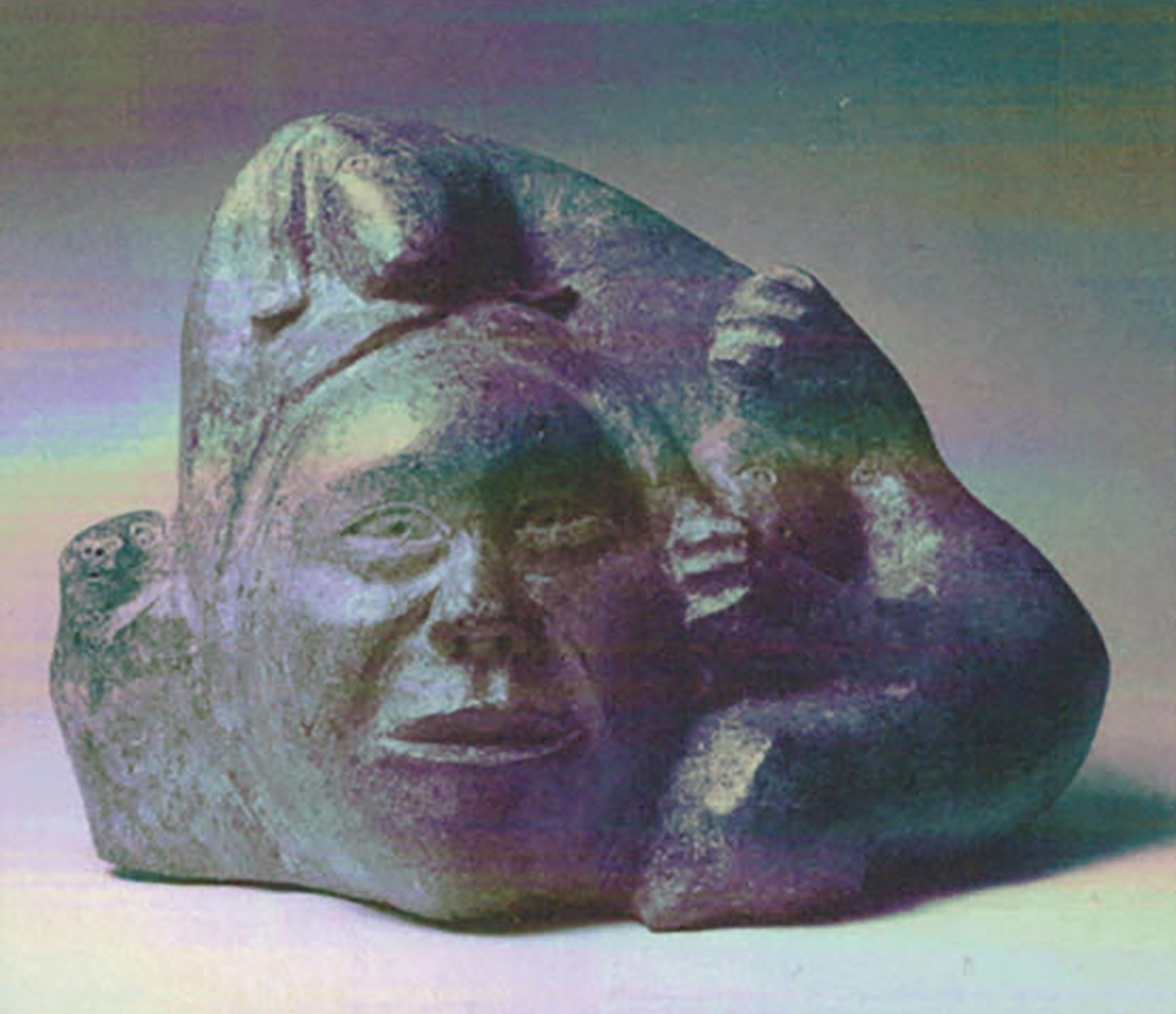

Peter Pitseolak, COMPOSITION, Cape Dorset, ca. 1968, stone 11.5 x 16 x 9 in.

Exhibition opened June 10, 2000

Introduction

Artists worldwide grapple with the materials they use to translate ideas into physical form and the Inuit are no exception. Some begin with the flat surface of a page on which to build up an image from inspired marks, while others work to free their subject from an existing substance such as stone. The materials chosen are ultimately means to an end; they enable artistic self-expression. Nevertheless, the use of certain media demands considerable technical know-how, and all require a random combination of inherent talent and learned process to render visible the imagination.

The materials traditionally available to Inuit artists were limited to those found naturally in the Arctic environment: stone, ivory, antler, bone and baleen. Graphic impulses historically directed to incising on tools or patterning in clothing were channelled by the widespread introduction of paper and drawing materials in the mid-20th century. Other introduced art techniques in the contemporary period have included printmaking, ceramics and metalwork. Such developments have expanded the visual vocabulary of the Inuit in recent generations as contemporary artists take advantage of increasing freedoms of expression.

The following pages review the major categories of materials available to Inuit artists, presenting both the classics and inspired exceptions.

Sculpture

Carving is the most longstanding and popular form of Inuit artistic expression. Works from the 1950s and 1960s tend to be small in scale, developing out of the nomadic traditions of Inuit life, while today’s compositions can be remarkably large. Many Arctic settlements have local access to good carving stone, although quarrying is by no means an easy task. Even within the single medium of stone, artists achieve great realism or expressive effect through surface modulation or varied stone colour.

In place of stone, the Inuit have always used other natural materials such as ivory from walrus or narwhal tusks, caribou antler, muskox horn, and bone from whales or land animals. Undoubtedly the artists take inspiration from the natural shapes of their chosen materials.

Kananginak Pootoogook, CARIBOU, Cape Dorset, 1997, ink, 20 x 26 in.

In the hands of a great artist, raw stone can be made to look as hard and sharp-edged as cast bronze or as soft and fluid as molded clay. Modern tools have enhanced the possibilities for fragile intercarving in which each void must be carefully cut away as the composition takes shape.

Artists often combine several materials to suit their subject. Inlays provide additional effect by colour contrast. Multiple materials may be combined for realism, for parts that would be difficult to sculpt in stone, or simply to complete the artist’s vision.

To view available sculptures, click here.

Drawings

The earliest drawings were made with graphite pencil. Coloured felt marker (‘pentel’) was used in the 1960s but was found to be fugitive if excessively exposed to light. A variety of other media have been used for drawing, including wax crayon, pencil crayon, ink and permanent black marker.

Artists seldom title or date their drawings, although some such as Kananginak Pootoogook have provided extensive descriptive captions. Cape Dorset drawings have often been catalogued in year ranges.

To view available drawings, click here.

Paintings

It is recorded that Peter Pitseolak became the first Inuk to try water-colour painting in the 1940s. Not until the 1970s were painting workshops arranged in Cape Dorset by visiting southern artist K.M. Graham who successfully introduced many Inuit artists to acrylic painting on paper. Over the years, independent explorations of the paint medium have been made by individuals such as Pierre Nauya (1914 — 1977) of Rankin Inlet and William Noah of Baker Lake, while oil stick painting on paper was explored recently by Sheojuk Etidlooie in Cape Dorset.

To view available paintings, click here.

Prints

The entire process of drawing on paper and making prints was imported to the north due to the lack of any indigenous materials. Various Japanese and European print techniques and papers have been employed over the years. The Inuit have established co-operative workshops where technical assistants contribute considerably to the printmaking process. Editions are small, usually limited to fifty prints. Annual collections from the Arctic studios are documented in illustrated catalogues, as are most special releases.

Sheojuk Etidlooie, PUIGI, Cape Dorset, 1999, etching & aquatint, 26.75 x 39.25 in.

Inuit printmaking started in Cape Dorset, beginning with the first annual release in 1959 and continuing to the present day. Four other Arctic print shops have produced annual releases: Puvirnituq and associate Arctic Quebec projects (from 1962 until 1989), Holman (since 1965), Baker Lake (1970 to 1990, and again since 1996) and Pangnirtung (1973 onward, excluding 1989 to 1991). Clyde River experimented with printmaking from 1980 to 1985.

Inuit prints bear several kinds of identifying marks, including Japanese-style name ‘chops’ for the printmaker, image maker and print shop, as well as blind embossed seals of the print shop or the Eskimo Arts Council (1961 — 1989). In addition to the artist’s signature, prints display a descriptive line in pencil which lists the title, artist, media, settlement, date and edition number. This appears in Inuktitut for prints from Arctic Quebec.

To view available prints, click here.

Stonecut

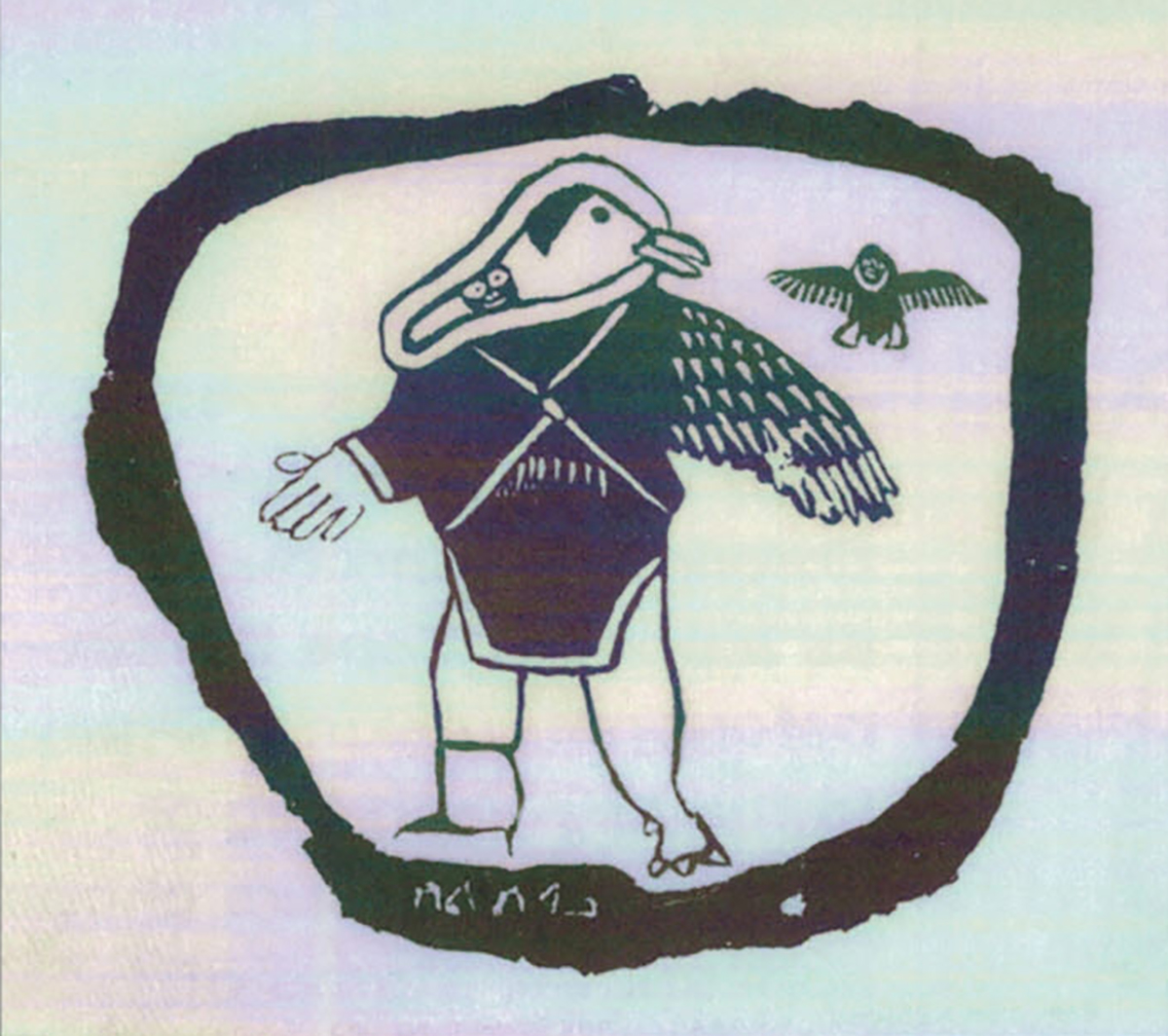

The Inuit print is perhaps most closely associated with the stonecut technique. This adapted Japanese relief printing process produces a full, bold image with crisp outlines. The woodcut printing process, as used occasionally at Baker Lake, is very similar, but starts with a flat board of wood instead of a stone.

Technical assistants are commonly used in the production of Inuit stone cut prints. The reverse outline of an artist’s original drawing is traced onto the flat surface of a large stone using tracing and carbon paper. The areas to be printed are left in relief, and the remainder of the surface is chipped away carefully. Ink is applied to the image surface in a single or blended colour and paper is laid on top and nibbed by hand to produce each print in the edition.

The stencil process produces a soft, subtle effect. The printmaker, who may be the image creator or a technical assistant, makes cut-out ’masks’ of stiff waxed card or plastic to cover areas of the paper that will not be printed. Ink is pounded into the open spaces using a flat stipple brush. Depending upon the complexity of the image and the number of colours, several masks may be required for each print.

To view available stonecut prints, click here

Davidialuk Alasua Amittu, ESKIMO WOMAN TRANSFORMED INTO A SEAGULL, Puvirnituq, 1968, stonecut, 14 x 15.25 in.

Lithography

The artist is free to draw directly onto the flat surface of a lithographic printing stone or metal plate, without the need for a technical assistant. Marks are made using a greasy substance such as a litho crayon or a tnsche wash. The surface is treated chemically to render the image area ink-receptive and the blank areas ink-repellent, then moistened so that the rolled ink will adhere only to the drawn areas. Paper is laid over the image and run through a printing press to transfer the ink. Lithographs can be printed in multiple colours. The process results in prints that often resemble the look of original drawings.

To view available lithographs, click here.

Engraving

To create an engraving an artist draws directly into the surface of a copper plate using a digging tool called a burin. Ink is rubbed into the incised lines but carefully wiped clean from the remaining flat surface. Damp paper is laid over the plate and rolled through a printing press, resulting in a linear image surrounded by an embossed impression of the edges of the plate.

The etching process also begins with a copper plate, however the artist draws with a sharp tool into a wax-like resin laid across the surface. The plate is immersed in acid and the image becomes deeply etched into the copper wherever the surface has been exposed along the drawn lines. Printing occurs as it does for engraving, with damp paper and the printing press.

To view available engravings, click here.

Ceramics

Beginning in 1963, the artists of Rankin Inlet used clay to give form to their imaginative visions. The imported skills of ceramic sculpting and firing were quickly acquired by the Inuit, however difficulties of reception and material supply led to the clo5ing of the program in 1975. A new generation of artists has revived Inuit ceramic art, forming an artists’ collective under the influence and support of the Matchbox Gallery in Rankin Inlet. In addition to bisque (uncoated surfaces) and the traditional ceramic glazes of the earlier era, today’s artists can choose a developed sawdust firing method to dramatically finish their fantastic

Textile Arts

Sewing skills now used in various Inuit textile arts evolved out of the traditional need for carefully constructed skin clothing and camp equipment. In the 1960s, fibre art workshops were held in Cape Dorset. Concurrently, the crafts program in Baker Lake began to encourage Inuit women to create wall hangings. In 1991, a weaving shop was opened in Pangnirtung, where artists’ drawings are translated on floor looms into limited edition tapestries.

Irene Tiktaalaaq Avaalaaqiaq, SPIRIT HEADS AND FIGURES, Baker Lake, 1996, Duffel, felt, embroidery floss, 54.5 x 54 in.

The distinctive images created by the Baker Lake wall hanging artists are among the most remarkable forms of contemporary Inuit art expression. Colourful cut felt forms are hand-stitched onto large spreads of stroud (light to medium weight wool) or duffel (heavier wool with a slightly fluffy pile). With or without appliqué, a variety of embroidery floss stitches may be added to embellish all or part of the surface.

To view available wall-hangings, click here.

Multi-Media

Stemming from traditional skills such as sewing and carving, arts and crafts programs across the Arctic since the 1960s have led to imaginative multi-media creations.

Many traditional dolls do not stand on their own rather were meant to be handled and played with. More recently, dolls have been made in a variety of formats, materials and poses and may be mounted by the artist for stability.

The artists of Nunavik (Arctic Quebec) have been known particularly for baskets made of woven tundra grasses. Such containers, originally used to carry water, are embellished with decorative stone or ivory pulls on their lids. Traditionally contrasting colour was provided by dark sealskin, but the artists today choose dyed grass or waxed thread.

Vignettes of traditional life and miniature replicas of tools and other artifacts form recurring themes in Inuit art. These creations may be meticulously reconstructed from authentic materials. or represented by creative substitutes.

Metalwork

Combining the physicality of sculpture and the linear impulses of graphics, metalwork is rapidly emerging as an exciting new medium of Inuit artistic expression. While a jewellery workshop was held in Cape Dorset as early as the 1960s, the cause has recently been taken up by the Arctic College whose courses provide access to the costly imported materials required for intricate work in silver, gold and copper.

Although the medium looks modern in the extreme, the artists have almost universally used it to render traditional and shamanistic themes. Perhaps the preciousness of the material lends itself particularly to these subjects.

There are countless ways to present a single subject, such as the totem-like arrangement of balanced figures. The results can be whimsical, spiritual, or visceral.