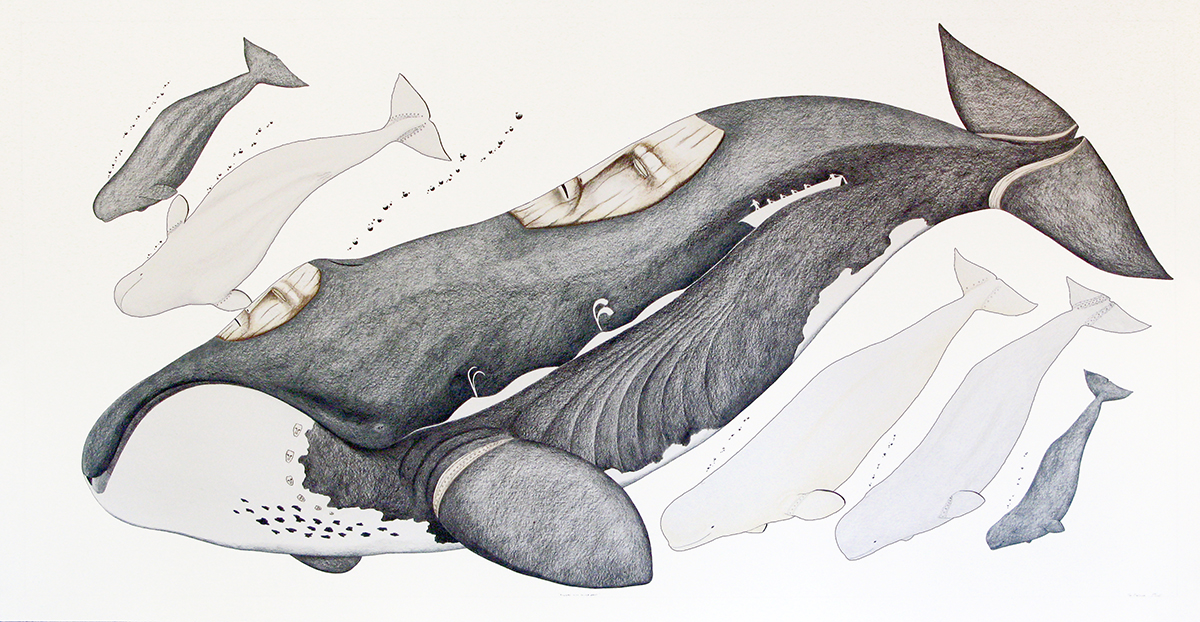

SEARCHING FOR BELUGA, Itee Pootoogook, Cape Dorset, 2010, coloured pencil, 30 x 44.25″

Exhibition opened June 10, 2011

The phenomenon of large scale drawings coming out of the community of Cape Dorset has attracted much interest by collectors and museums in the past few years. The initial offering of large format paper to the arctic community of Cape Dorset has been relatively recent. William (Bill) Ritchie, Studio Manager of the Kinngait Studios in Cape Dorset, began working on large format watercolour paper in his own art practice during the late 1980s while he was involved in the Kinngait Studios. This format not only impacted his own artwork but was also a process he brought back to Cape Dorset in the mid-nineties when he returned to manage the studios. Terry Ryan, former head of Dorset Fine Arts, had encouraged Bill, and the many other artists who had visited the community to mentor artists to share their practices and techniques. With this in mind Ritchie brought a number of heavy rolls of Arches 330 gr. watercolour paper up north. He soaked them in garbage bags overnight then stretched them on specially prepared ¾” backers with cross members on the back to stop the boards from torquing under the stress exerted by the drying heavy paper.

The first artist to use this large format watercolour technique was the late Arnaqu Ashevak. In 2002, he painted seal oil running between his hands with watercolour paint. Later, the illustrious Kenojuak Ashevak used the same paper although she preferred to use pencil crayons to watercolour paint. The watercolour experiment did not take off at the Co-op studios but the large paper remained intriguing to some of the artists. Soon after, Shuvinai Ashoona created her own large scale work comprised of 20 x 26” sheets joined together for the creation of a topographical view of Cape Dorset measuring, at its widest, 55 x 130”. The Co-op hence ordered five huge rolls of drawing paper from Woolfitt’s in Toronto and subsequently large-scale drawing became a discipline unto its own at the studio.

ALL KINDS OF SPIDERS IN DIFFERENT VIEWS, Shuvinai Ashoona, Cape Dorset, 2011, Ink 32.5 x 49″

Significantly, in 2005, then emerging artist Annie Pootoogook started working on a large drawing destined for her exhibition at The Power Plant in Toronto on a scale of four by eight feet. This was the first time she worked in this scale and was encouraged to do so. She started a spectacular drawing of the new freezer at the local Co-op store. According to Bill Ritchie, Annie was used to working alone and found the work difficult with the distractions of drawing in the co-op. As a result, he took the large panel to her apartment and set it up for her there. It was a huge effort on behalf of Annie and the studio but the result was a wonderful drawing, entitled Freezer (2006) that was quickly purchased by the National Gallery of Canada, raising the bar for purchases of contemporary Inuit drawings.

The positive museum reception for this larger format work is due to the drastic change in Cape Dorset’s artwork. These large drawings, so different not only in format, but in content, produce strong statements that appeal to institutional collections. While there are some artists who prefer to work at home, Ritchie asserts that certain artists enjoy working together in the studios for a variety of reasons, and that is why they work on more ambitious drawings in the studio rather than at home, where their space and tools will remain just as they left them for when they return.

According to Ritchie each artist has a different approach to the paper surface. He states that Itee Pootoogook, whose work can be very intricate and subtle, and so can take a very long time to complete, prefers not to work in large scale, but rather in a smaller format. One of the exceptions in this exhibition is the bow of a canoe, entitled Searching for Beluga (2010).

BOWHEAD WITH BELUGA WHALES, Tim Pitsiulak, Cape Dorset, 2011, Ink, coloured pencil, 49 x 97″

Shuvinai Ashoona, known best for her involved ink drawings, often works entire days on a large-scale drawing – a process that allows her to vanish into her work and her mind, according to Ritchie. Her contemplative, often fantastical, drawings seem to expand over the paper as she allows her mind to wander over the surface. An exquisite example is an ink drawing, All Kinds of Spiders in Different Views (2011).

Tim Pitsiulak’s work is highly realistic and illustrative. Ritchie encourages Tim, along with all the artists, to work larger which, at times, can be a challenge but he always enjoys a challenge. He wants to push himself as an artist, both technically and stylistically. Pitsiulak typically draws examples of wildlife or machinery seen in his environment, mixed with spiritual symbols of ancient Inuit past. His depiction of animals is impressive as seen in Bowhead with Beluga Whales (2011), a pencil crayon drawing of a bowhead surrounded by beluga whales drawn with pencil crayon, that measures a stunning four by eight feet. To date, his large scale works have been made with pencil crayons but most recently he has begun to work with oil stick.

Ohotaq Mikkigak, who has been an active member of the Cape Dorset arts community since the early 1960’s is now doing wonderful drawings up to eight feet long. His works speak to the past and things he has seen like the Cape Dorset community and the surrounding landscape. He draws with vigor, says Ritchie, often to the point of cramping his hands from his thorough, layered colouring on such a big scale. His wax-like surfaces of pencil crayon are highly worked and his composition and mastery of the increased scale is noteworthy. The large drawing, entitled Composition (Houses in Cape Dorset) (2011), is spectacular.

COMPOSITION (HOUSES IN CAPE DORSET), Ohotaq Mikkigak, Cape Dorset, 2011, Ink, pencil, coloured pencil 49 x 97″

Jutai Toonoo, whose work is unique among his contemporaries blossoms in large scale. His subject matter comprises mainly of portraiture and landscapes – infusing them with his bold interpretations. His larger-than-life portraits envelop the space of the paper, bursting with energy and colour, exemplified in Worried (2011) and Smiles (2010). His work is dominant and powerful, placing Jutai in a category of his own – much more conceptual and abstracted than what many southern audiences identify as Inuit art.

Notable in this collection of large scale drawings by Cape Dorset artists is the inclusion of many of the senior artists from the community that have previously been known for small-scale drawings or prints. Mayureak Ashoona, Kakulu Sagiatuk, Pitaloosie Saila, and the late Meelia Kelly, all born in the early 1940s, are now incorporated into this exhibition of large format drawings.

The art of the Inuit is constantly changing and adapting, much like the culture itself. Ritchie confirms that drawing has come of age. The studio has lithography, etching, stonecut and drawing. He says that the studio now routinely orders thousands of Derwent pencils, reams of paper in every colour and they have adapted the studio so the artists can comfortably work on large-scale drawings. In the past, drawings were primarily a vehicle to source images for the Annual Print Release. Now, while interest in the prints remains strong, it is these stunning original drawings which have captured a new audience of museums and collectors alike.

Nancy Campbell