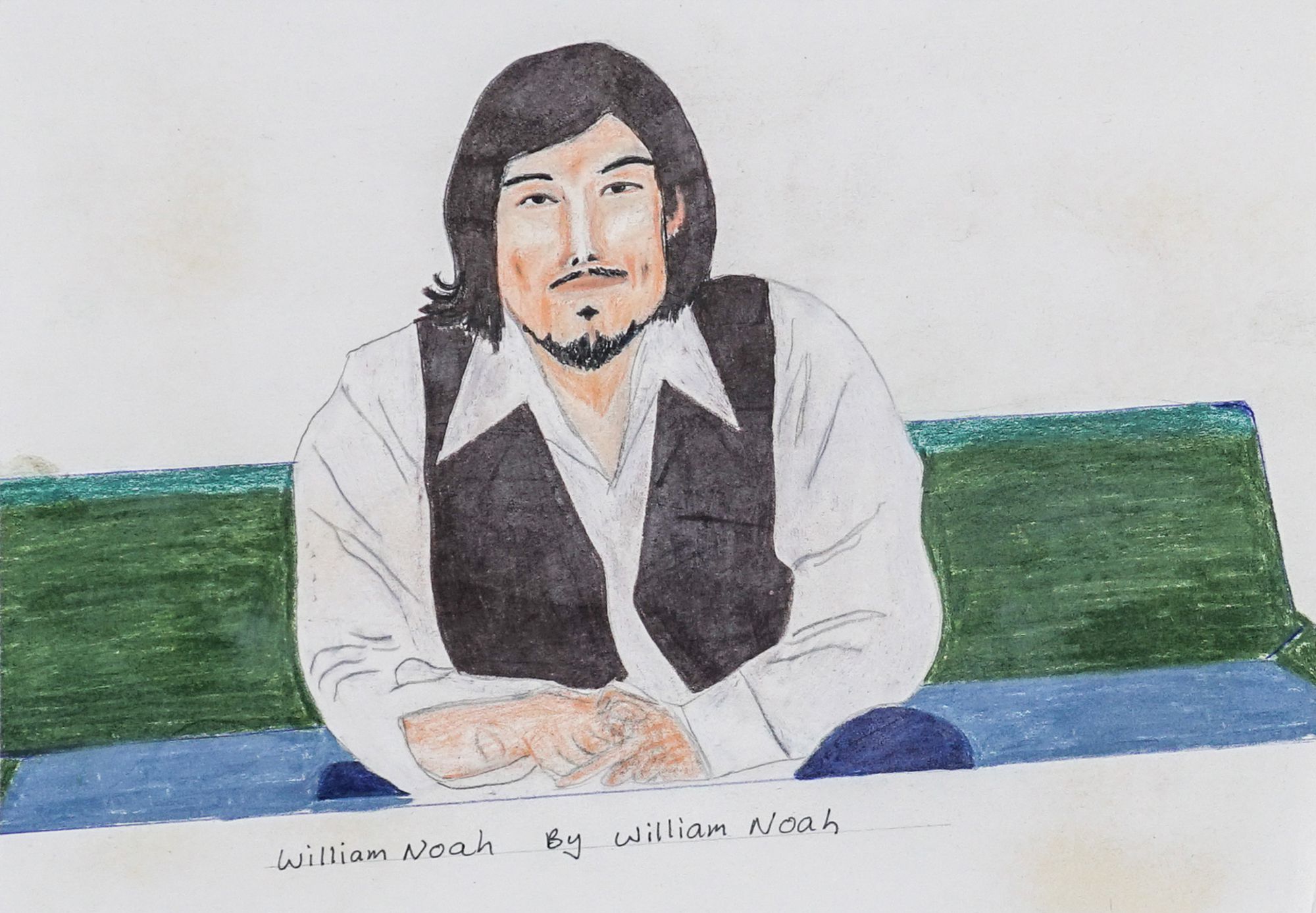

William Noah, WILLIAM NOAH BY WILLIAM NOAH, coloured pencil, graphite, 8 x 11 1/2 in.

Exhibition opened March 6, 2021

Feheley Fine Arts is honoured to present Life by the River: William Noah (1943–2020), an exhibition of paintings and drawings by Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake) artist, William Noah. This exhibition marks the first since Noah’s passing in July 2020. During the gallery’s previous solo for the artist held in 2010, Noah and his wife and daughter, Martha and Abbygail Noah, travelled to Toronto for the opening and established close ties with Pat Feheley. After Noah’s passing ten years later, they sent all of the works from his studio in Qamani’tuaq to the gallery in Toronto. This showcase of over thirty-five drawings and paintings created in the latter three decades of his career, between 1993 and 2018, pays tribute to Noah’s remarkable life as an artist, family man, and community figure.

Noah’s story, like his artistic style, is unique in its own right. Born at his family’s camp in Back River (Haningayok), N.W.T. (now NU), hardship prompted their move to Qamani’tuaq when Noah was a pre-teenager. There, he was among the first Inuit youth to attend federal day school. As he got older, he accumulated an incredibly impressive CV, including everything from construction work to the Nunavut Minister of Finance’s Executive Assistant. He married Martha Noah—marriage was something he felt destined to do since birth [1]—and together they raised a family and made seasonal visits back to Noah’s childhood home in the Back River area. Throughout everything Noah maintained a phenomenal artistic practice for most of his life, beginning in the mid-1960s in the printshop at Qamani’tuaq’s Sanavik Co-op.

The selection of works in Life by the River are a testament to Noah’s artistic talent and the highly representational drawing style he developed throughout his fifty-year-long career. He himself came from a family full of artists: his mother was renowned graphic artist Jessie Oonark (1906–1985) and three of his sisters were also recognized artists working in textiles and the graphic arts: Victoria Mamnguqsualuk (1930–2016), Janet Kigusiuq (1926–2005), and Nancy Pukingrnak (b. 1940).

It is known that for many artists working in the arctic, the familial influence can be quite strong. Many are encouraged to try their hand at drawing, sewing, or carving by a family member who has seen success, thus learning from them and often building on elements of their family member’s style while developing their own. Artist Jack Butler, who worked with Noah in Qamani’tuaq for many years, has noted that Noah retained some aspects of Oonark’s style in his early prints of x-ray-like figures and animals, sharing her “hieratic perspective and formal clarity.” [2] Yet Noah’s work was also infused with influences from western culture, “inflected with imagery from comic books, Sunday school papers, phonograph record jackets,” and informed by western visual conventions like linear perspective and communicating a narrative through storyboard techniques. [3] Noah’s brilliance was evident in his act of straying off the beaten path to forge a style entirely his own through use of the various influences available to him.

William Noah, KITCHECUT TRIPS IN MANY DIFFERENT YEARS 94-10, 2010, coloured pencil, graphite, 22 1/4 x 30 in.

The Life and Work of William Noah

William Noah lived a remarkable life. In 1943 he was born in the Back River area of the Northwest Territories, on the cusp of the end of the Second World War. The semi-migratory hunting lifestyles that most Inuit led at the time had been made complicated by a reliance on Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) trading posts. But when the fur trade dried up in the years leading up to WWII, relations between Inuit and HBC traders became strained. This, along with hardship endured by changes in caribou migration patterns in the Kivalliq region, prompted many Inuit to move into settlement communities. Noah was part of this first generation to transition from a land-based camping lifestyle to settlement life in a permanent community; from subsistence hunting to participating in a cash economy. Noah’s story began at the threshold of this transition.

For Noah’s family, the point of transition was prompted by the death of his father. Noah was ten years old. As the sole son in a family of sisters—over nine at one point [4]—and too young yet to take over his father’s duties, Noah’s family decided to move to the settlement of Qamanit’uaq a few years later. In an interview transcribed for the 1972 Baker Lake Print catalogue, Noah explained the difficulties his family faced during that time:

“For a few years after [my father] died my uncle and my brother tried to look after us but there were too many of us. My father was a real hunter who knew how to take care of a big family. After his death we had hard times with no food and poor clothing.” [5]

Noah lived the first decade of his life in the Back River area where he absorbed the traditional ways while travelling with his elders, learning the skills of hunting, trapping, and fishing. Around forty years later, Noah would revisit the Back River area for the first time since childhood, this time with his own family. The emblematic moment is depicted in Noah’s drawing After Forty Yrs, Went Back Home 1994: Kitchecut (2018). Using a storyboard or montage technique, Noah visually stitches together his memories of visiting the area known as Kitchecut annually since 1994. In the 1995 catalogue Qamanittuaq: Where the River Widens, Noah speaks about the importance of taking the time to be present in nature:

“In the Inuit way of living, you have to associate with the land, mountains, hills, and even the sky. Otherwise, you will get really frustrated and you won’t really know what is wrong with you. That is the way to be peaceful, to create a rest in your mind. The town cannot relax you. The people cannot give you peace. But when you are out there, you come back refreshed.” [6]

The use of the storyboard to convey a narrative or a sequence of events was a technique Noah often used in his work. His process was informed by photographs taken on trips: of his family, the local animals, the rivers and canyons in the Back River area, as well as images of himself. In Noah’s many self-portraits, he would depict himself as seen through the lens of a camera, either as a man in his youth, fishing in his kayak, or even taking a mirror “selfie,” such as in his work Kitchecut Trips in Many Different Years 94–10 (2010). Here, Noah foregrounds the influence of the camera on his drawings and paintings.

William Noah, HERMANN RIVER CANYONS, 2012, watercolour, 22 x 30 in.

Qamani’tuaq was one of several communities in the Canadian Arctic to implement artmaking co-operatives. In this model, Inuit could make a living wage by trying their hand at artmaking and selling their works back to the co-op, which was owned and operated by members of the community. Artists like Noah began to make work through the Sanavik Co-op in the 1960s while he was in his 20s. It was a move that seemed almost natural for Noah, whose family was already seeing great success and encouragement for their artistic skills. Martha Noah, Noah’s wife, also became a printer and would collaborate with her husband on prints for the annual collections. Notably, Noah was one of the very few artists in Qamani’tuaq who continued to make and sell art long after Sanavik’s early years.

Noah may have been known initially for his prints, but his later work focused on drawing and even painting with acrylics, a medium not often used in the North. The Sanavik Co-op began purchasing drawings from Noah in 1969 and from then on, the artist’s drawing oeuvre began to take shape. Noah’s drawing style was representational, which was another element of his practice uncommon to artists in the Kivalliq region. As the years went on his technique became increasingly more naturalistic in both subject matter and style. Jack Butler, who had worked closely with Noah for many years including on collaborative exhibitions in the South, articulated that the biggest difference between Noah and other Qamani’tuaq artists lay not only in his style, but in his approach. Noah saw art as a process, and his ability to maintain and develop an exceptional practice over the course of fifty years, while working various jobs and travelling across the arctic and southern Canada, is further testament to that fact. Noah led a remarkable life and leaves a profound legacy with tremendous potential to encourage a new generation of young artists in Qamani’tuaq. [7]

Notes and Sources:

[1] Baker Lake Print Catalogue 1972 (Baker Lake: Sanavik Co-operative, 1972), unpaged.[2] Jack Butler, “How Canadian Artists Earn Money: North vs. South,” in Art and Cold Cash (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2009), 149.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Marion E. Jackson and Judith Nasby, Contemporary Inuit Drawings (Guelph: Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, 1987), 111.

[5] Baker Lake Print Catalogue 1972 (Baker Lake: Sanavik Co-operative, 1972), unpaged.

[6] Marion Jackon, Judith Nasby, and William Noah, Qamanittuaq: Where the River Widens (Guelph: Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, 1995), 129.

[7] Jack Butler, “How Canadian Artists Earn Money: North vs. South,” in Art and Cold Cash (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2009), 149.

[*] From William Noah’s first-hand account of his life, Baker Lake Print Catalogue 1972.

To view available artworks by William Noah, click here.