Sheojuk Etidlooie, ABSTRACT COMPOSITION, 1999, Oil stick on board, 20 x 20 in.

Exhibition opened February 24, 2024

Contemporary Drawing in Kinngait, 1995–2015

Drawing holds a long history at the Kinngait Studios. For many artists it served as their introduction to artmaking, as graphite pencil and paper were among the first media available to in the late 1950s and early 1960s. While drawings were purchased by the co-op, they were seldom marketed for sale and prints dominated the market for over 40 years. [1] In the 1990s, drawings would finally pique the interest of collectors—ironically, by way of prints.

Kickstarting the Drawing Revolution: Sheojuk Etidlooie

In 1995, newcomer Sheojuk Etidlooie debuted three images in the Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection characterized by repetitious amorphous animal and human figures—a far cry from the more traditional styles that had dominated print collections up until that point. [2] Her images garnered interest in both the North and the South and led to an exhibition of her original drawings at Feheley Fine Arts in 1998. Similar to her prints, Etidlooie’s original drawings were more vibrant with roughly drawn outlines complemented by the patterning of varied applications of colour. With her distinctive style, Etidlooie paved the way for a generation of contemporary drawing artists in Kinngait.

In the 1999 posthumous exhibition Transformed: The Last Works of Sheojuk Etidlooie, drawings made with oil stick, a crayon-like amalgam of oil paint, were included. Oil stick could not be used for fine detail, but the broad strokes of the stick left behind satisfying, fully saturated pigment. Etidlooie embraced this new medium, seen in the gestural approach and strong colours of Abstract Composition (1999). Oil stick would soon become a staple of the Kinngait Studios as it was embraced by many including Arnaqu Ashevak, Shuvinai Ashoona and Jutai Toonoo. Oil stick works by each artist can be found in this exhibition.

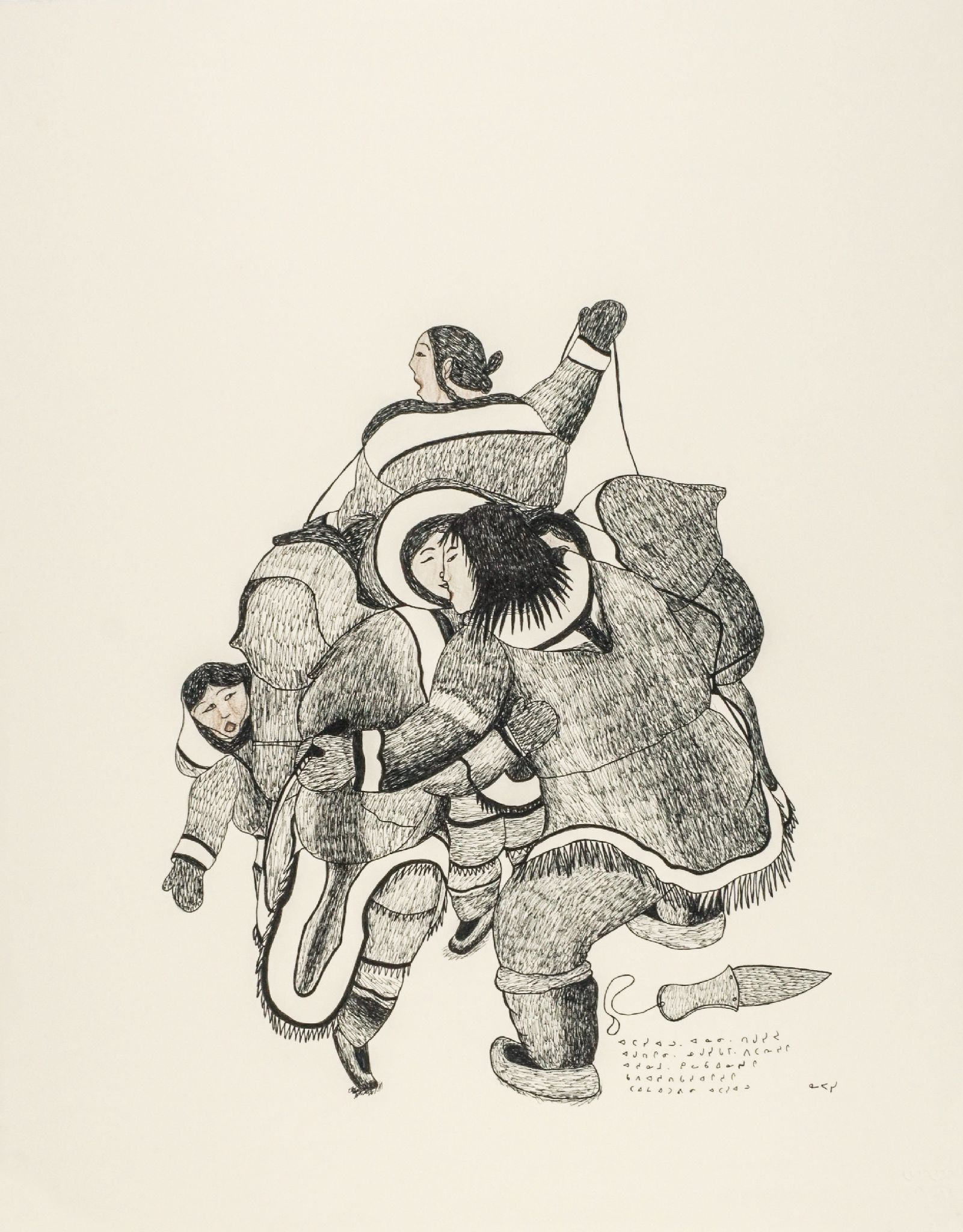

Napachie Pootoogook, COMPOSITION (ENTWINED), 1996, Coloured pencil & ink, 26 1/4 x 20 3/4 in.

Expanding Subject Matter: Napachie and Annie Pootoogook

At the same time as Etidlooie’s rapid rise to fame, Napachie Pootoogook’s happier drawings increasingly began to show the harsh reality of aspects of traditional life, moving away from some of the depictions found in images made by her mother, Pitseolak Ashoona. Pootoogook’s compelling ink drawing Composition (Entwined) (1996) seemingly depicts a romantic scene but is marred by the panic and dismay on the faces of the two background figures. [3] This set the stage for her daughter, Annie Pootoogook whose drawings were first introduced in the early 2000s at Feheley Fine Arts. Pootoogook stated that she could not depict the “old ways” as she did not live them; she could only draw about her own life. The drawings were fresh, based on everyday life in Kinngait—they varied from people watching television at home, to couples being intimate as in Lover’s Embrace (2003-04), to tough depictions of abuse, and much more. Through her realistic style and innate colour sense, Pootoogook created candid snapshots that immediately resonated with viewers. Pootoogook’s star rose quickly as she garnered national and international recognition for her drawings. [4]

Studio Regulars Get Innovative: Qavavau Manumie and Kananginak Pootoogook

Qavavau Manumie, a master of stonecut printing techniques, has also always been a graphic artist. In the early 2000s his imagery became increasingly eclectic, ranging from pop culture subjects like Donald Duck, to chilling drawings of poignant global events like the attack on the Twin Towers, as depicted in Composition (9/11) (2001). He continues today to create works which highlight the adverse effects of pollution and global warming on the Arctic. Kananginak Pootoogook, known for his naturalistic drawings of birds and animals, soon transitioned his subject matter including a portrait of himself drawing a wolf and an intimate portrait of himself and his wife. The drawing Caribou Fighting (2008-09) highlights his ability to capture the exact likeness of animals while the large-scale makes this drawing more intense and monumental. [5]

Innovation in Scale: Arnaqu Ashevak, Shuvinai Ashoona, Ohotaq Mikkigak

In 2002, the exceedingly experimental artist Arnaqu Ashevak created a watercolour drawing titled Misigarq (Rendered Oil) (2002) measuring 44 x 36 inches, twice the size of the typical Kinngait drawing. According to then-studio manager Bill Ritchie, this was the first large-scale drawing to emerge from the Kinngait Studios. Shuvinai Ashoona also expressed an interest in larger paper, having created a monumental overview of Kinngait by attaching many smaller sheets together. Later, Ritchie would order four-foot-wide rolls of paper to the studio which could be cut into any length the artist preferred.

Ohotaq Mikkigak, PINK AND GREEN SUNSET, 2013, Coloured pencil, 24 5/8 x 49 1/2 in.

By this time, a new dedicated drawing studio had opened, allowing artists the space to work on bigger drawings. The impending decade saw an explosion of energy in the studios. Ohotaq Mikkigak and Shuvinai Ashoona, both previously known for their small-scale detailed ink drawings, quickly adapted to large-scale and filled their drawings with colour. The work Pink and Green Sunset (2013) shows Mikkigak’s successful adoption of modulated colour variations, verging on Colour Field painting. [6] Ashoona’s imagination took form in her similarly colour-filled drawings like Many People Going Out of Amauti (2006).

Studio Newcomers: Itee Pootoogook, Tim Pitsiulak, Jutai Toonoo

Three significant new artists joined the drawing studios between 1998 and 2000. Itee Pootoogook was discouraged from drawing in the 1980s as he based his work on photographs rather than the more typical subject matter, which was deemed unappealing to a southern market. Later, he was welcomed into the new drawing studios. His subjects, based on old photographs, became timeless in his serene and evocative “still life” drawings like Outpost Camp (2011). Intrigued by the new vitality of the drawing studio, Tim Pitsiulak also began creating drawings. He split his time between hunting and drawing, celebrating the land with its abundance of wildlife. The drawing Floe Edge (2010) is no doubt a self-portrait. The luminous pencil crayon on black paper shows a hunter returning home, pulling his boat behind him after a day of hunting from the floe edge.

Tim Pitsiulak, FLOE EDGE, 2010, Coloured pencil, 30 x 44 in.

Jutai Toonoo, known for his thoughtful text-based sculptures, brought new life into the studios with his bold, gestural style and haunting self-portraits. Oil stick allowed him to make daring statements such as the isolated image of a mask with distorted features, made more powerful by the saturated oil-based strokes. His same energetic approach enlivens a large watercolour drawing of waves crashing up against the coastline in Stormy Sea (2010).

During this brief twenty-year period, the artists of Kinngait embraced the new media, varied scale, and freedom of imagery. To go into the studios in 2013 was to witness the most extraordinary dynamism and vitality; Itee Pootoogook at his desk, rolling his chair back and forth to contemplate his unfinished drawing; Shuvinai Ashoona sitting at her table, or often laying on it, to work on a large scale drawing; Tim Pitsiulak quietly drawing with his ear phones on; Jutai Toonoo standing at an easel, working at a furious pace and, in the quiet back room, alone, elder Ohotaq Mikkigak peacefully at work.

Beyond Kinngait

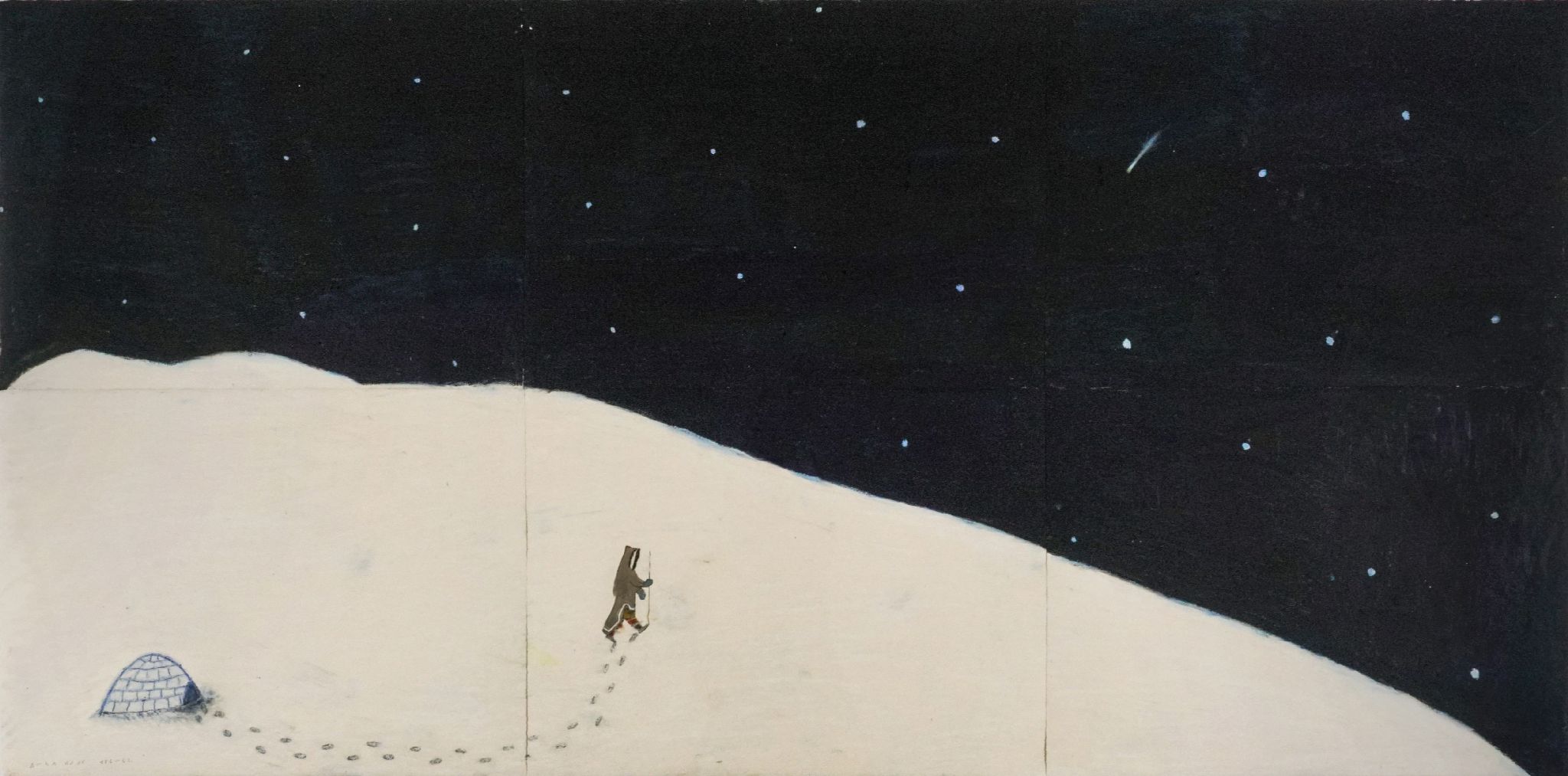

In an incredibly brief period, these artists pushed forward the concept of contemporary drawing both in Kinngait and beyond. Exploration of scale and different media spread to other settlements, most notably in Pangnirtung, NU where Elisapee Ishulutaq was using oil stick as early as 2012. Untitled (Lone Hunter on the Land) (ca. 2014) is a masterful image created in oil stick and in monumental scale; the lone hunter a small but strong focal point amid a vast landscape.

The years following 2015 have seen an even greater flourishing of contemporary drawing in Kinngait. Today, the stunning new drawing studios is teeming with talented graphic artists including Ningiukulu Teevee, Quvianaqtuk Pudlat, Padloo and Nicotye Samayualie, Johnny Pootoogook, Ooloosie Saila and Saimaiyu Akesuk, as well as a host of new younger artists who are all encouraged to join. Today, the next phase of contemporary drawing is well underway.

Elisapee Ishulutaq, UNTITLED (LONE HUNTER ON THE LAND), Oil pastel, 44 x 90 in.

Endnotes

[1] Kinngait Studios is a division of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative.

[2] The complete essays of of the 1998 and 1999 Sheojuk Etidlooie exhibitions at Feheley Fine Arts are available here: Transformed: Sheojuk Etidlooie: Original Drawings, The Last Works of Sheojuk Etidlooie

[3] For more information about Napachie Pootoogook’s late series of drawings see: Leslie Boyd Ryan, Napachie Pootoogook (Winnipeg: The Winnipeg Art Gallery, 2004).

[4] Annie Pootoogook’s first solo exhibition was held at Feheley Fine Arts in 2003. In 2006, her works were exhibited in a solo exhibition at the Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto, ON. That same year Pootoogook won the prestigious Sobey Art Award and was invited to the Glenfiddich Artist in Residence Program in Scotland. In 2007, Pootoogook’s drawings were featured in Documenta 12 in Kassel, Germany.

[5] This drawing is featured on the cover of the exhibition catalogue: Ingo Hessel, Kananginak Pootoogook (Toronto: Museum of Inuit Art, 2010).

[6] See the exhibition: Blue Cloud: Jack Bush & Ohotoq Mikkigak, Justina M. Barnicke Gallery, University of Toronto, 2012. Also featured in the exhibition catalogue: Nancy Campbell, NOISE GHOST (Toronto: Art Museum at the University of Toronto, 2015).