This year’s annual Cape Dorset print collection included a number of showstopping prints featuring recognizable arctic subject matter. From the whimsical kamik-wearing owl in Ningiukulu Teevee’s dynamic lithograph Stepping Out, to Pauojoungie Saggiak’s open-mouthed char in First Catch, to Nicotye Samayualie’s luminous nocturne Silaqtiq (Bright Evening), the animals and landscapes of the Canadian arctic dominated the graphics of 2020.

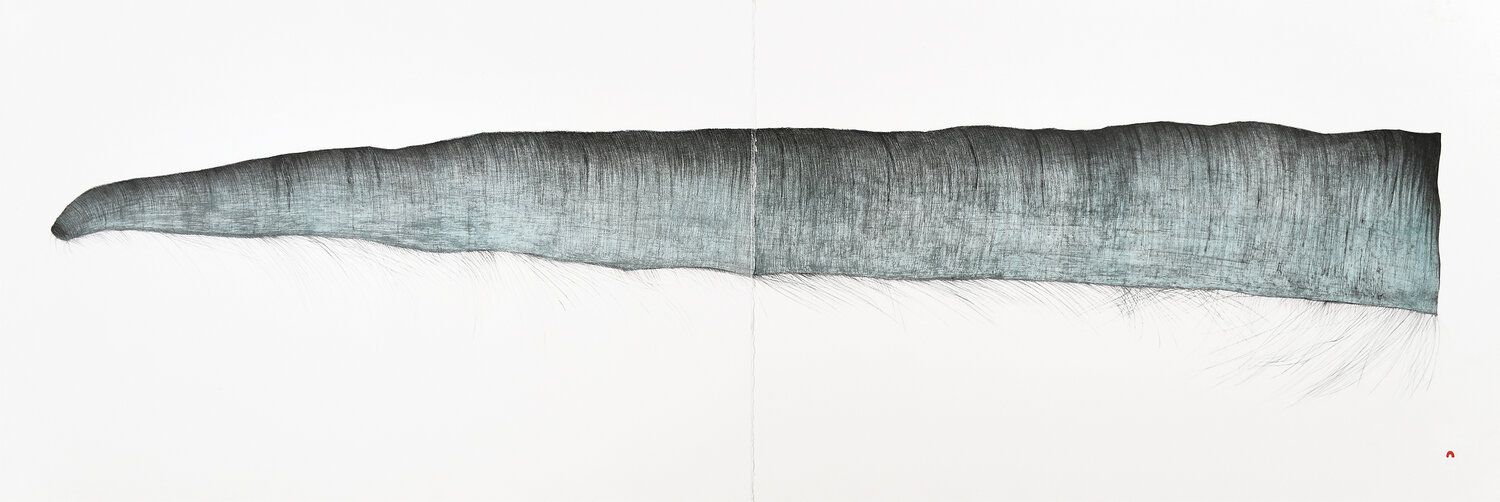

Perhaps less recognizably familiar was the special release print Baleen by Shuvinai Ashoona—a meticulously detailed seven-foot-long diptych of a form which, at first glance, is mysterious. Verging on abstraction, the long greyish-blue form is tentacle-like, reminding us of themes from Ashoona’s depictions of octopi monsters and creatures with elongated limbs. Being quite different from the rest of the print collection, not representing wildlife nor landscape elements, the piece raised some eyebrows while installed in the gallery. What was it?

Shuvinai Ashoona, Baleen, 2020, lithograph (diptych), edition of 30, 28 1/8 x 87 in.

What is baleen?

Baleen is a material that comes from a variety of whales including bowhead, blue, and humpback, to name a few. The material functions as a filter-feeding system inside the mouths of baleen whales as its keratin composition (also found in our hair, skin, and fingernails) gives baleen a bristle-like texture, ideal for catching small crustaceans and fish. Imagine this: the whale opens its mouth underwater, taking in water and small sea creatures like krill and shrimp. The whale then pushes the water out and the bristles trap the nutritious goods in. The sheer size of a whale’s mouth allows much small sea life to be trapped for consumption. Therefore, the baleen must be just as large and can sometimes be up to twelve feet in length.

For a sense of scale, here’s Emily next to an 8 ft. baleen at the gallery (Emily is 5’4”).

Baleen that comes from the Canadian arctic is primarily from the bowhead whale; often those that are legally hunted for community subsistence purposes. Other times it simply washes up onto the shore. Inuit have hunted bowhead whales for thousands of years as a crucial food source necessary for the survival of their communities. When European whaling ships arrived in the 1700s, commercial whale hunting practices inevitably drove bowheads to near extinction in the late 1800s. This prompted a government mandated ban on whale hunting which negatively impacted Inuit communities, despite their subsistence hunting intentions.[1]

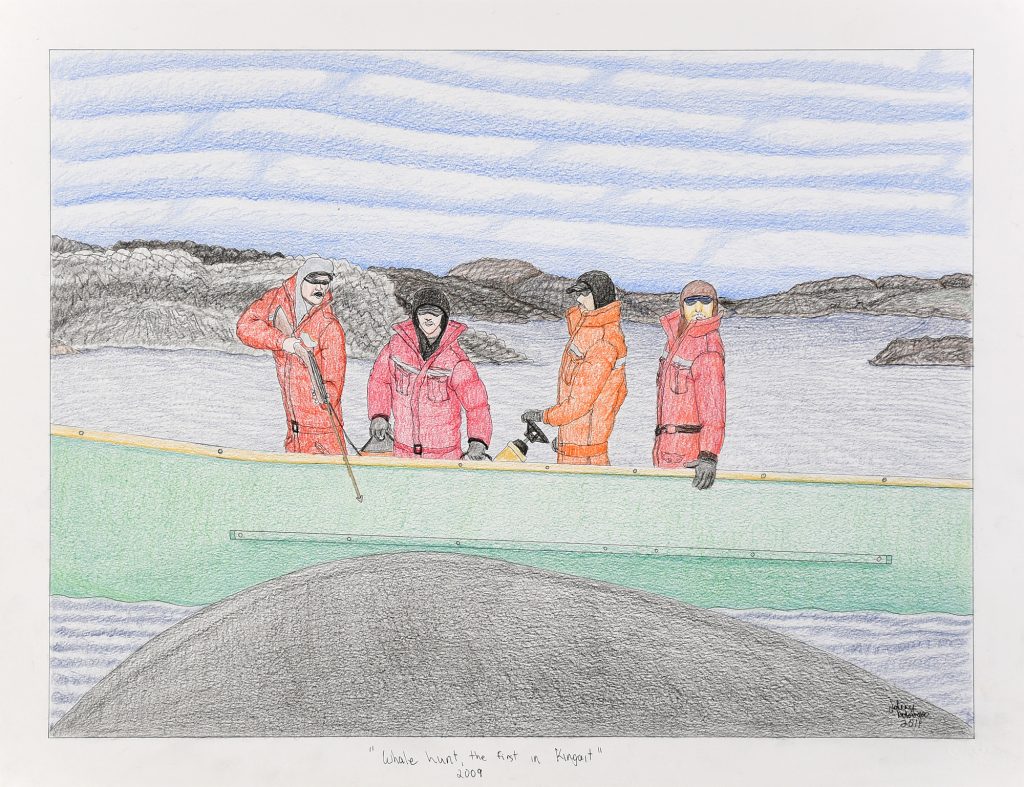

In 2015, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans set a quota of five whales to be hunted each year to safely revive the Inuit tradition of the whale hunt. Hunting opportunities were distributed across each of the Regions of Nunavut: two to the Kivalliq region (home to Arviat, Qamani’tuaq, Rankin Inlet, and more), two to the Qikiqtani region (Baffin Island), and one for Kitikmeot (home to Gjoa Haven, Taloyoak and several more communities).[2] Kinngait received the bowhead whale hunt in 2009, which was the first time artist Johnny Pootoogook remembered in his lifetime. Pootoogook was born in 1970.

Johnny Pootoogook, Whale Hunt, The First in Kingait, 2009, 2011, coloured pencil and ink

Baleen in Inuit culture and art

Stiff and sturdy yet also flexible and stringy once peeled, baleen was traditionally used for a variety of purposes. Baleen strings, for example, were used to tie a harpoon and its point together. The strings also functioned well as fishing lines, snares, and could be woven into fish weirs. [3] Iñupiaq in Alaska began the practice of weaving beautiful intricate baskets (aguummaq) out of baleen strings in the early 1900s, a practice that continues on today.

In Inuit art, baleen is used as both medium and subject. Some sculptural works include small pieces for inlaid detailing, such as for eyes, and sometimes small implements like knives or harpoons would be crafted out of the material. Solid pieces of baleen can be polished and carved into pendants, brooches, or other ornaments. Contemporary artists have found unique and creative new uses for the material in their work, such as Uriash Piuqiqnak’s use of baleen string as hair in his electrifying sculpture Frightened by Lightning.

Uriash Puqiqnak, FRIGHTENED BY LIGHTNING, 2019, stone, baleen, antler, 13 x 9 x 7 1/2 in. In this sculpture, baleen was used in both the inlaid eyes and for the hair.

The use of baleen as an artistic subject brings us back to Shuvinai Ashoona, who is among the first to depict baleen as an entity in and of itself, separate from the mouth of the whale. Ashoona was inspired to tackle the subject by a piece of baleen housed in the Kinngait Studios where she works, and in 2018 created a series of drawings based on the material. Drawings included depictions of fantastical rainbow baleen, people holding pieces of baleen that towered over their heads, and the single piece of baleen that went on to be used for her phenomenal lithograph for the 2020 print collection.

While ambiguous and perplexing to those who may be unfamiliar, baleen is in fact an important part of Inuit material culture and history. It’s the depictions of these lesser-known aspects that allow these significant histories to be told, which is what makes works like Baleen so very important.

To learn more about the Inuit bowhead whale hunt, see a variety of videos on the subject produced by Isuma TV here.

Shuvinai Ashoona, COMPOSITION (CREATURE PRESENTING DRAWING), 2018, coloured pencil and ink, 23 x 29 7/8 in.

Sources

[1] Hellen Fu, “When Whaling is Your Tradition,” Royal Ontario Museum, https://www.rom.on.ca/en/blog/when-whaling-is-your-tradition.[2] Sarah Rogers, “Four of Nunavut’s five bowhead tags approved for 2019,” Nunatsiaq News, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/four-of-nunavuts-five-bowhead-tags-approved-for-2019/.

[3] Julie A. Lauffenburger, “Baleen in museum collections: its sources, uses, and identification,”Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, https://cool.culturalheritage.org/jaic/articles/jaic32-03-001_3.html.