Osuitok Ipeelee, OWL, 1964, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), stone & ivory, 7 1/4 x 7 x 3 in.

Foreword

The world is by now familiar with the art of Cape Dorset, but few know the man behind the scenes who has facilitated and furthered this international success.

Forty years have passed since Terry Ryan’s first visit to Cape Dorset in 1958. His arrival in the north coincided with a period of dramatic change in the Arctic. The traditional Inuit lifestyle was rapidly changing through increased exposure to the south, and men and women with strong ties to the old ways found new voices as artists in this evolving environment. Terry is one of very few individuals to have experienced first-hand the remarkable flowering of Inuit contemporary art during the past four decades.

In 1960, Terry became the first non-native employed by the Inuit, and he has been an advisor and friend to generations of Inuit artists. To have lived and worked with the artists during this important period of change was a unique opportunity. The circumstances have never and will never be duplicated. An artist himself, Terry brought with him to Cape Dorset a discerning sensitivity which complemented this remarkable opportunity. Terry has received many honours for his work in encouraging Inuit art. These include an Honourary Fellowship from the Ontario College of Art and the Order of Canada.

Cape Dorset is located on the southern coast of Baffin Island in the North West Territories of Canada. The Inuit call the place Kinngait, a name which describes the undulating hills surrounding the protected harbour of the site. In 1956, James and Alma Houston, under the initiative of the Department of Northern Affairs, established a craft centre in the growing settlement. Three years later the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative was formed to encourage the growing artistic community by providing an economic base focused on the arts. Soon after, when the Houstons decided to leave Cape Dorset, Terry Ryan assumed the role of art advisor and ultimately manager of the growing co-operative. Under his guidance the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative has nurtured and promoted the talents of the Cape Dorset artists over the last four decades. The graphic arts have become an exciting component of artistic activity at the Dorset Co-op, complementing the activities of the sculptors. The unfailing excellence and explosive success of contemporary Cape Dorset art are a result, in part, of the supportive continuity provided by Terry over the years.

Cape Dorset Sculptors are recognized for their intricate compositions, creating stunning and powerful works of art from local materials. Acquiring enough stone for the sculptors and for the early print blocks presented recurring problems. As sites were depleted, Terry and the artist members of the Co-op spent summers searching out new local deposits to fill the ever-increasing requirements of the burgeoning art community.

The artists who were first involved with the Dorset Co-op are among the most famous in Inuit art, and Terry, a fellow artist, was their advisor, friend and co-worker. His reserve, constancy and sense of humour allowed him to weave seamlessly into the Dorset community. Today, he serves not only as the General Manager of the Co-op, but also as a Justice-of-the Peace for the community and Coroner for the region. He has shared joyful and sorrowful times over the years with the people of Cape Dorset.

Abraham Etungat, OWL AND YOUNG, 1972, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), stone, 9 1/2 x 8 x 3 1/2 in.

The Ryan Collection: Early Cape Dorset Sculpture is a selection of Inuit art from Terry Ryan’s private collection. The sculptures in this exhibition were acquired selectively during his years of residence in the north, and reflect his knowledge, interest, and support. These treasures range from works by individuals who rarely sculpted to classic compositions by great masters of Inuit art, such as Tudlik, Kenojuak Ashevak, Latcholassie Akesuk, Osuitok Ipeelee, and Pauta Saila.

In the late 1960’s, during the first of many trips to Cape Dorset, I was privileged to meet many of these artists, and to witness firsthand the bond between Terry and the thriving Dorset art community. Over the ensuing years I have watched this bond strengthen, and, with the rest of the world, have admired the wonderful results. While each sculpture is for us a beautiful work of art, for Terry it is a crystalized memory, an evocation of places and events far removed from the gallery settings.

These works, and the men and women who made them, are documented on the following pages. They form a unique testimony to this remarkable and historic period in Canadian Art and to the dedication and sensitivity of one man. It is with great pride that Feheley Fine Arts presents this exhibition of early Cape Dorset sculpture from the Ryan Collection.

Patricia Feheley

May, 1998

Rememberances: Dorset in the Early 60’s

July of 1960 began a lifetime association with the then small settlement of Cape Dorset. Although my first visit to Cape Dorset was in 1958, it was limited and somewhat one-dimensional. I was a visitor, and my memories, though clear and visual in one sense, were largely restricted to people engaged with distractions of ship-time – the annual ‘sealift’.

Having spent time in the Arctic prior to taking up residence at Cape Dorset, I found some things familiar and not unexpected. I had lived since 1956 in North Baffin, as well as Greenland. On returning from Greenland in late 1959, I found my access to the Arctic once again difficult to obtain. So I sought another diversion and travelled to Vancouver Island to take up what I thought would be the beginnings of a career in Museum administration at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. It was not to be.

Shortly after moving to Vancouver, I was notified by a past professor from the Ontario College of Art – the late George Pepper – that a position was being developed at Cape Dorset for the summer of 1960. This contract position was sponsored by the Department of Norther Affairs and would be under the direction of the resident government administrator, Mr. James Houston. It fulfilled my desire to return to the north.

After several false starts due to the government bureaucracy, I returned east to board the ice-breaker C.D. Howe at the port of Montreal and to sail north to an unexpected lifetime vocation. Dorset in the 60’s was a small trading post, as were most Arctic communities, consisting of the ubiquitous Hudson’s Bay Post and a small Catholic Mission occupied by a lone Oblate priest. There was as yet no RCMP detachment. The harbinger of the government presence we know today was the recently established position of Northern Service Officer, occupied by James Houston. He and his late wife Alma Bardon greeted my arrival.

Sheokjuk Oqutaq, SITTING DOG, ca. 1965, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 6 x 3 1/2 x 7 1/4 in.

The welcome was warm and casual, as all things north of 60 were at the time. My accommodation was a small, single-room building known in government parlance as a ‘rigid frame’ – the forerunner of a number of government-inspired housing designs. It was the winter home of a man I would come to know well, Kananginak Pootoogook. He had made it available to me as he and his family had moved back on the land for the summer months.

I recall it was painted entirely in silver paint – walls, floor and ceiling! I felt I had awakened in a large foil liner. The truth be known it was the only paint available at the time, and Kananginak had wanted to ensure that his small home was neat and clean for his visitor from the south.

As it transpired I was seldom in the house during those summer months, as I too was attracted to the great outdoors and the invitations from both Inuit and the few non-Inuit that made up this tiny community.

Adjacent to the Houstons’ home was a small rectangular building – not much bigger than an elongated walk-in closet. This room served as the government office and occasional storage room for stone sculptures. While I marvelled at the limited collection of small stone sculptures that lined the shelves of this little building, it was while visiting the many outlying camps that summer of 1960 that I was so forcibly struck by the talent of these northern artists.

I continued to aspire to create my own works on paper. This endeavour attracted some comment on what I was doing in my hesitant water-colours and, more importantly, provided an introduction to what my new-found companions were doing in their creative efforts. Having the singular opportunity to observe these men and women take up their pieces of stone and create such small marvels, when the spirit moved them and time from the more pressing need to find sustenance allowed them, truly impressed me.

Many times, an unfinished sculpture was left on the beach to be revisited hours, days and even weeks later. I can recall visiting camps vacated by their inhabitants – gone off to hunt, gather berries or travel to the Trading Post – where examples of unfinished sculpture lay awaiting the return of their creators among the flotsam and jetsam of rifles, harpoons, nets and animal carcasses.

Throughout the 1960’s and into the 70’s, while people were as yet not fully caught up in the transition to the new community life, most sculptors found the peace of mind and the tranquility of space there on the land to complete these small stone wonders.

In the ensuing months (indeed years) after my arrival at Cape Dorset, I became increasingly aware of the relationship between carver and carving. There were works that could not possibly have been done by a personality other than the author of the piece being proffered.

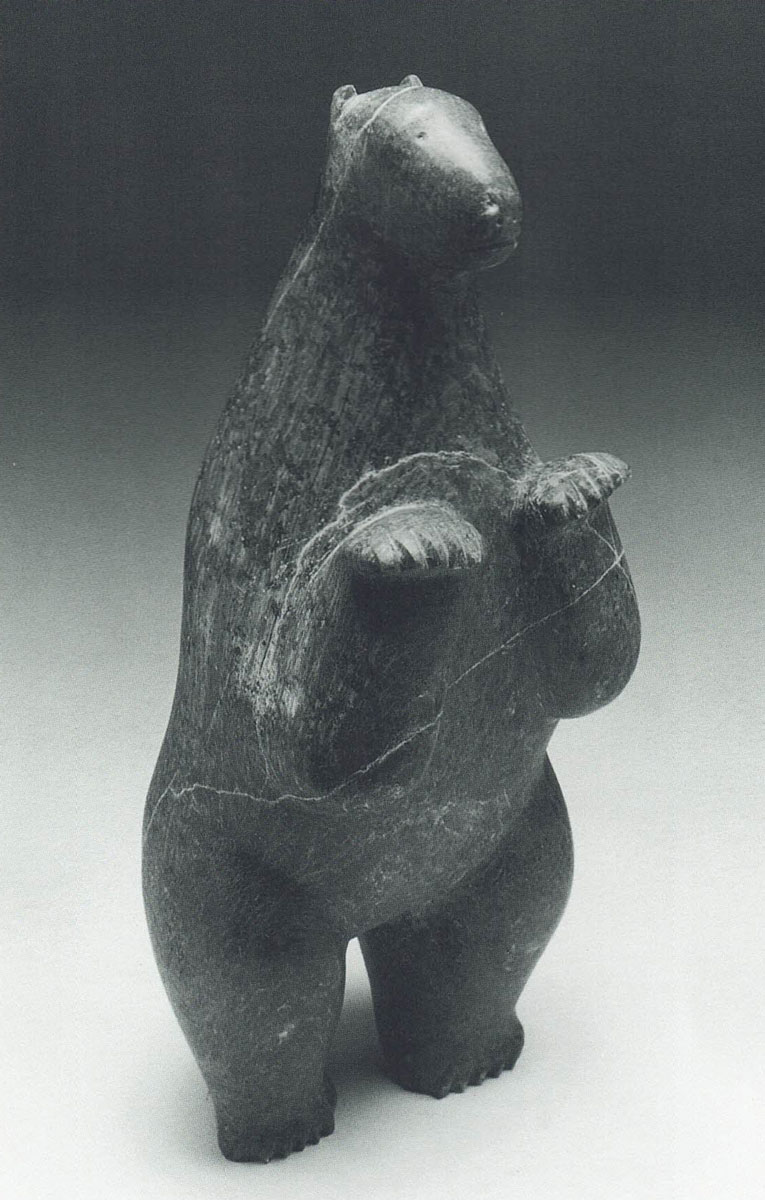

Pauta Saila, STANDING BEAR, 1962, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), stone, 16 1/2 x 7 x 5 in.

Latcholassie, then a man in his early middle age, would accompany his father, the late Tudlik, when the latter brought his small personal pieces for comment and sale. Tudlik was losing his sight at that time but his small works in stone expressed a much greater image than was apparent in this man’s physical circumstance or demeanour.

Latcholassie too, then and in the ensuing years, would reflect this contained imaginary and very personal approach to his work. Not unlike Parr, who never carved but whose drawings reflected that rare ability to call forward another time and place, his work was guileless and sincere. This newfound expression allowed them an unexpected opportunity to communicate with an audience they never anticipated.

Kiakshuk commanded a more respectful presence, as he was a man known in the past to be an influential camp leader and rumoured Shaman. Kiakshuk usually appeared in the company of younger members of his family, often with his son Lukta, then engaged in the early print project. Unlike others whose social standing was less noted, Kiakshuk by his very presence would dictate a certain expectation in his presentation of a finished work. One was expected to take note, listen to the explanation of what was being offered and to appreciate that offering with due respect. To do otherwise was disrespectful and insensitive. This was also true with men like Peter Pitseolak, Kingwatsiak, and others of that older generation.

Among the women who carved, Mary Qayuaryuk had this particular presence as well. In the ensuing years Kenojuak Ashevak would build her own formative international reputation on that same very personal inner strength.

Needless to say, there were many other individuals of truly great talent like Osuitok Ipeelee whose ability to express himself in stone is legendary. The late Sharky Nuna, Koomwartok Ashoona, his recently departed brother Qaqaq and the ever exuberant Kiawak are other examples of artists who reflect an ability that remains to this day an enigma in its scope and concentration.

My late friend, and consummate craftsman, Sheokjuk Oqutaq is of particular significance to me. He was a man I admired enormously not only for his talent but for his dedication to his many responsibilities, his reserved demeanour, yet capricious deeds.

There are many anecdotes, of course, most amusing and some less so; occasions where the personality of the carver expressed itself most compellingly. But anecdotes aside, the milieu of the time was conducive to such free self-expression. The lack of pressure and limited distractions (radio, TV, material attractions) allowed the past and the passing generations both the time and the concentration necessary to so ably express themselves in stone and on paper. This is regretfully less apparent today.

As one can appreciate, the respectful and receptive reaction of the buyers of this early work created a growing desire on the part of the sculptors to communicate with this distant audience., The monetary return was of course an incentive, but less than today. As with many efforts in the ensuing years to collect drawings in North Baffin, what was so evident in this period was a strong desire to communicate an awareness of a passing era.

Camp life was disappearing with the introduction into the Arctic of so many new, puzzling and disruptive forces. This new milieu was viewed with concern and apprehension. It is, in retrospect, regrettable that many of those thoughtful and studied explanations by the authors of the works presented were sometimes misunderstood or not fully appreciated. In large part this was due to the limitations imposed by a new language and the distractions of the moment, crowded as it was with so many events.

Certainly the majority of carvings in this small collection make their own strong visual statement. In their directness and tactile appeal one can feel the force of a declaration made with true honesty and price – pride of craft and pride of culture.

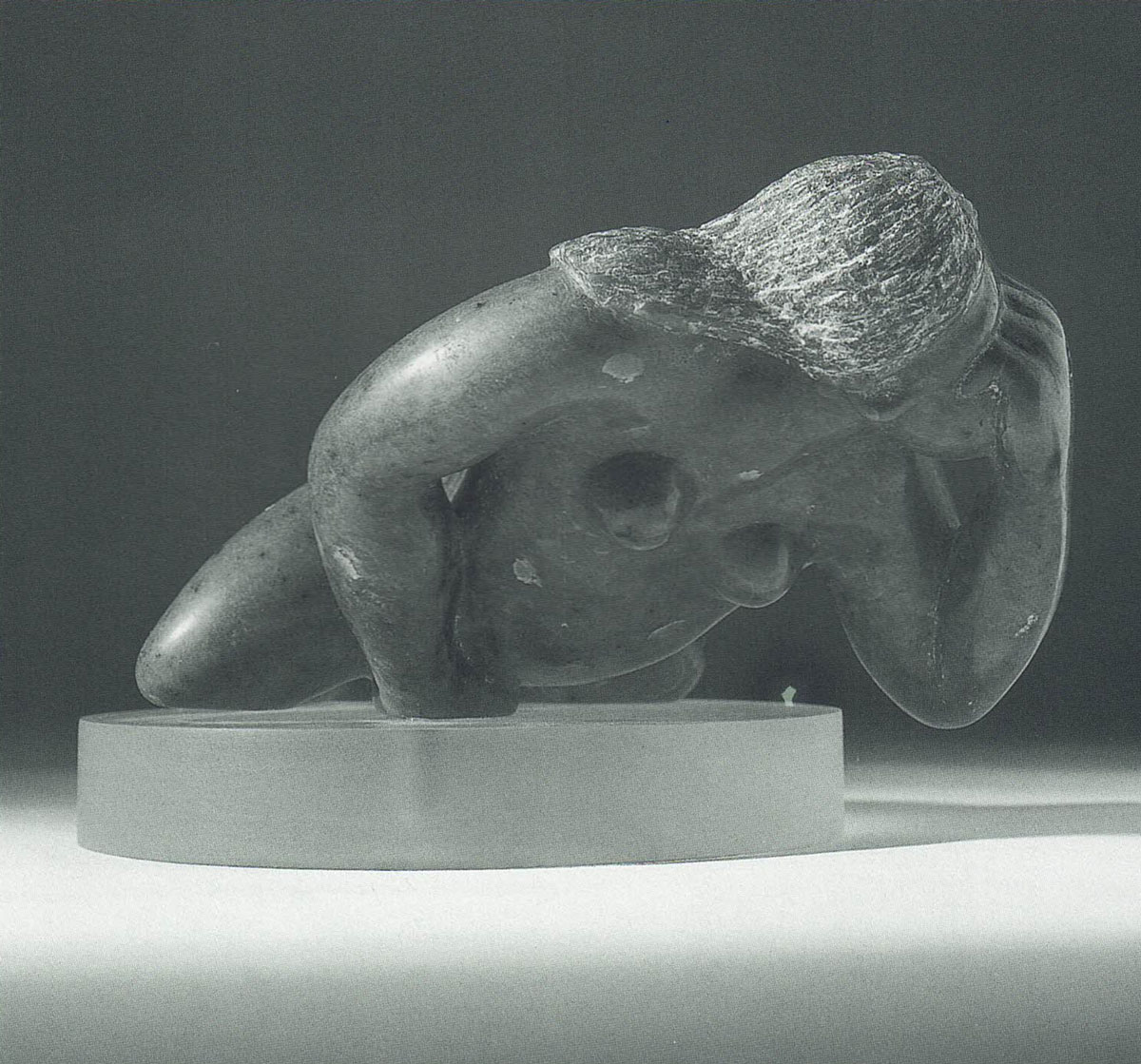

Qaqaq Ashoona, HEAD OF A WOMAN, 1967, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Stone, 10 x 11 x 5 in.

Terry Ryan

Cape Dorset, March, 1998

Notes on the Artists

Latcholassie Akesuk

The work of Latcholassie Akesuk is immediately recognizable because of his distinctive bird and human forms. Born in 1919, his work was first exhibited in 1953, as part of an exhibition held in London at Gimpel Fils, and later in the Masterworks. His biography is extensive and his work is represented in many major public and corporate collections. Latcholassie’s expressive animal/human creatures are rendered with reserved surface markings and a stark minimal form strongly reminiscent of the sculpture of his father, Tudlik.

Adamie Alariaq

Gorn in 1930, Adamie lived in both Kimmirut and Iqaluit before his death in Cape Dorset in 1990. He was the half-brother of Kenojuak Ashevak and the father of the well-known sculptor Novoalia. Adamie would often select exotic subjects for his sculpture, which were no doubt suggested by subject matter seen in books or films.

Kenojuak Ashevak

Kenojuak is undoubtedly the most famous of all the Cape Dorset artists. Known primarily for her distinctive graphics, she has always maintained a concurrent interest in sculpture. Kenojuak was born in 1927 in a camp near Cape Dorset and still lives in the settlement. She is the recipient of many awards, including two honourary doctorates, and she is a Companion of the Order of Canada. She is the subject of several books and a film. Her work has been exhibited extensively, both nationally and internationally.

Qaqaq Ashoona

Qaqaq and his brothers, Koomwartok, Kiawak and Namoonai are songs of the famous graphic artist, Pitseolak Ashoona. An early member of the Dorset Co-operative, Qaqaq was a great supporter of the organization throughout his life. He was born in 1928 and died in 1996. He is survived by his wife, Mayureak, who is also well-known for her distinctive graphics and sculptures. Together with his brothers, Qaqaq is numbered among the finest of the Dorset sculptors. His powerful figures convey quiet spirit and dignity.

Koomwartok Ashoona

Koomwartok was another son of Pitseolak Ashoona, the famous graphic artist. As a result of his early death, Koomwartok’s work is not as well-known as that of his brothers, Qaqaq and Kiawak. He was born in 1930 and died in 1984. His wife Mary is a talented graphic artist and sculptor, as is their son Salomonie. Koomwartok’s flamboyant and lyrical abstractions of birds and animals are the most recognizable compositions of his varied subject matter.

Davidee Mannumi, WOman with BUckets, ca. 1967, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Stone, 7 x 5 x 2 in.

Abraham Etungat

One of the oldest active artists in Cape Dorset today, Etungat was born in 1911. Although he is best-known for his delicate depictions of birds with raised wings, the subject matter of his sculptures is quite varied. His depictions of figures and animals, often in family groups, are both imaginative and finely sculpted. He is a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and his classic ‘Bird of Spring’ has been cast in bronze. These monumental sculptures are on public display in Vancouver, Calgary, Halifax and Toronto.

Osuitok Ipeelee

When the Houstons travelled to Cape Dorset in the 1950’s, they were told by the Inuit themselves that Osuitok Ipeelee was the finest artist in the south Baffin Coast. This local opinion is shared universally as Osuitok has become one of the best known and most admired of the contemporary Inuit sculptors. He as born in 1923. His sculpted portrait of Queen Elizbeth was presented to her in 1959 and his work adorns the mace of the Northwest Territories. He is an honoured member of the Royal Canadian Academy and his work was included in the Masterworks exhibition. His subject matter is as remarkably broad as his style, ranging from naturalistic depictions of animals and narrative scenes to wonderful abstract compositions. His sculpture is characterized by a careful balancing of mass, fine surface finish and delicate detailing.

Joe Jaw

Joe was born in 1930 on Nottingham Island near Coral Harbour. He died in Cape Dorset in 1987. His brothers, Pudlo and Oshutsiak Pudlat, were both well-known graphic artists and his wife, Melia, is also an artist. Joe’s sons, Mathew Saviadjuk, Pootoogook Jaw and Salomonie Jaw are all active and well-respected sculptors. The use of fine detail and finish in this sculpture is surprising and delightful.

Salomonie Jaw

Salomonie Jaw was born in 1954 into a family of artists. Both of his parents, Joe and Melia Jaw, and his brothers, Mathew Saviadjuk and Pootoogook Jaw, are established artists. The detailed and finely carved composition by Salomonie included in this exhibition was created when he was very young.

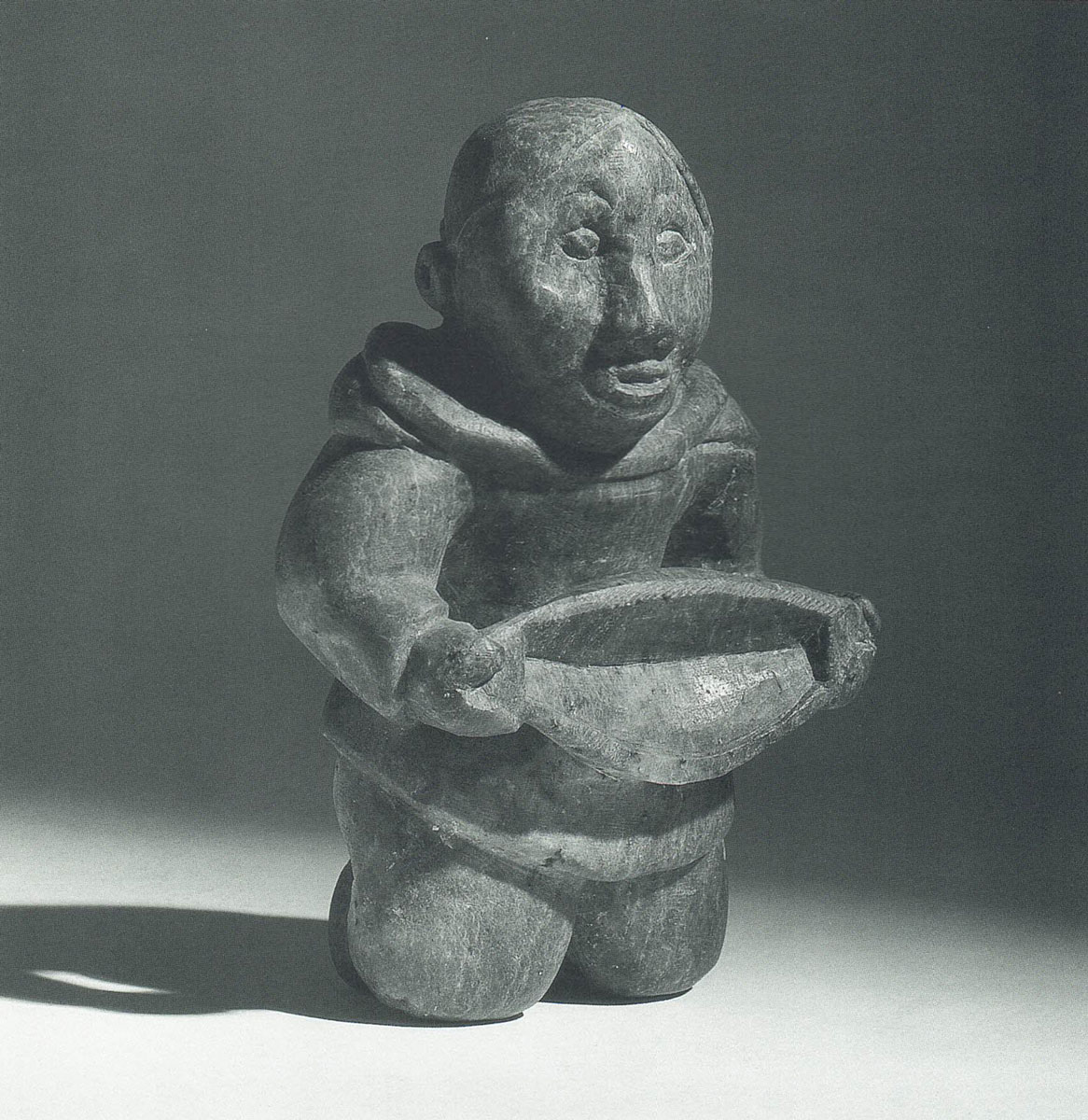

Kiakshuk

Known primarily as a graphic artist, Kiakshuk was also an accomplished sculptor. His children, Paunichea, Ishuhungitok Pootoogook and Lukta Qiatsuk have followed in his footsteps. Born in 1886, Kiakkshuk lived in nomadic camps until he settled in Cape Dorset where he was one of the founding members of the Co-operative. He died in 1966. His interest in recording the old ways was echoed in his additional role as a storyteller. Kiakshuk’s print ‘Summer Tent’ was reproduced on a Canadian stamp.

Davidee Mannumi

Born in 1919, Davidee Mannumi is the father of Aqjangajuk Shaa and Tukiki Manomie. His wife is the well-known artist Paunichea. This work by Davidee, not a prolific artist, is a classic example of traditional Inuit subject matter and sculptural style.

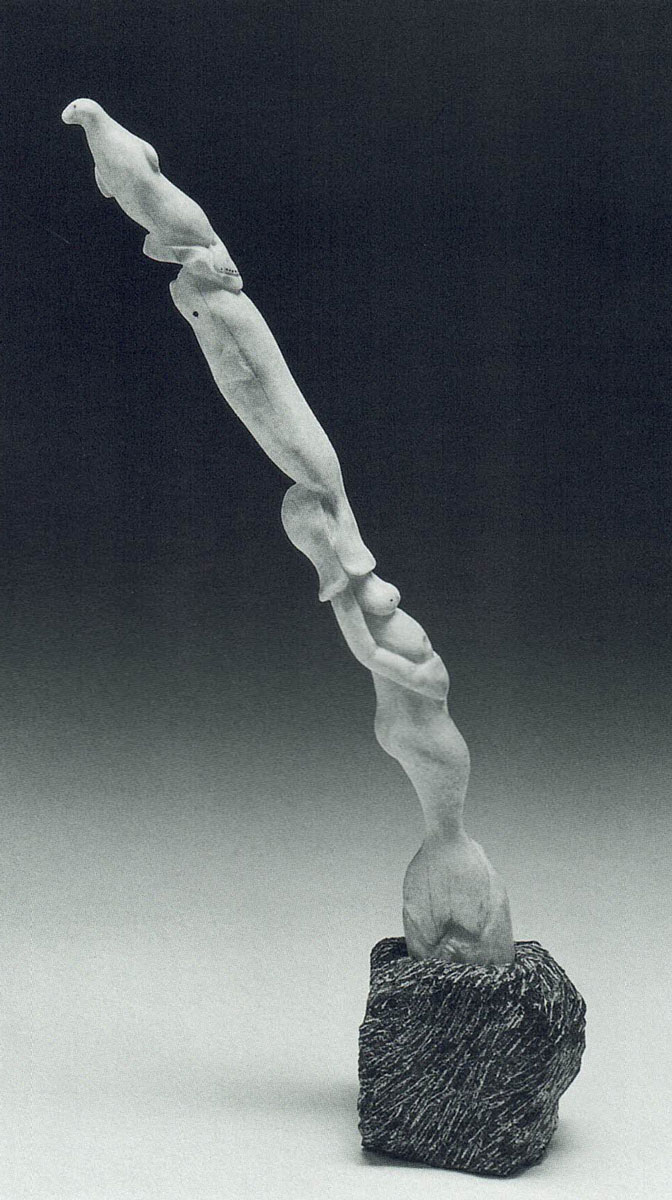

Kellypalik Qimirpik, Senda Totem, ca. 1974, Stone & ivory, 11 1/2 x 5 x 2 1/4 in.

Tukiki Manomie

Tukiki is the grandson of Kiakshuk and the son of Paunichea. His brothers are Aqjangajuk Shaa and Qavavau Mannumi. Tukiki has already had many solo exhibitions, including several in the United States and Europe. Born in 1952, he bridges the period of transition in the Arctic from traditional to more modern ways. His work is noted for remarkable technical skill combined with imaginative subject matter in flowing, complex compositions.

Ohotaq Mikkigak

The husband of Qaunaq, Ohotaq was born in 1936. In the early years of printmaking he was active as a graphic artist before turning to sculpture. Throughout much of his life, Ohotaq has worked full time at the Cape Dorset school and so produced works of art only when truly inspired. His brother is well-known printmaker Pee Mikkigak.

Qaunaq Mikkigak

Qaunaq was born in 1932 and lived the traditional life on the land until moving to Cape Dorset in the late 1950’s. Her mother was Mary Qayuaryuk who was both a sculptor and an accomplished graphic artist. Qaunaq has also made jewellery, and she claims to be one of the first women in Cape Dorset to work in stone. Her work was featured in the exhibition Inuit Women Artists and is extensively reproduced in the catalogue. Birds, women and shamanic transformations fill her sculptures.

Sharky Nuna

Another of the older generation of artists whose work is instantly recognizable, Sharky Nuna was renowned for his simple and direct sculptures of animals and humans. A quiet, shy and diminutive man, he was respected as a hunter as well as an artist. Sharky was born in November, 1918 and died tragically in a boating accident with his son, Josephee, in November, 1979. He is the grandfather of Toonoo Sharky.

Elisapee Nungusuituq

Although her work is not widely known, Elisapee Nungusuituq worked as both a sculptor and a graphic artist. The sculpture by Elisapee included in this exhibition is typical of her lyrical depictions that make full use of negative space and inter-carving. She was born in 1927 and died, after a lengthy illness, in 1985.

Sheokjuk Oqutaq

Sheokjuk, who was born in 1920 in a camp near Cape Dorset, was the half brother of Osuitok Ipeelee and Innuki Oqutaq. He lived part of his life in Lake Harbour before moving to Cape Dorset where he became the carpenter for the Dorset Co-op and where his friendship with Terry Ryan blossomed. Sheokjuk died in 1982. Best known for his delicate and almost translucent depictions of loons and fish, he also carved amazingly inventive transformation compositions. His remarkably skilled handling of the stone was precursor to the characteristic Dorset sculptural style of today.

Kiakshuk, Kneeling Woman with Kudlik, 1963, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 7 x 4 1/2 x 3 in.

Peesee Oshuitoq

Peesee Oshuitoq was born in 1913 and died in Cape Dorset in 1979. In the early 1950’s he began to create sculptures which were characteristically small and involved an amazing degree of detail. These are well-known through extensive reproduction in publications about Inuit art. Although he was not a prolific artist, Peesee Oshuitoq’s sculptures are admired for their monumental, expressive power despite their small scale.

Omalluq Oshutsiaq

Omalluq was born in 1948, and raised with her brothers, Etulu and Kellypalik, by the notable artist Etidlooie Etidolooie and Kingmeata Etidlooie. Omalluq has served on the board of the Inuit Art Foundation. She particularly enjoys carving ‘mother and child’ groupings, although the range of her subject matter is quite broad. The sculpture by Omalluq included in this exhibition refers to the ever-present religious influence which has increasingly become a part of northern life over the last century.

Aoudla Pee

Born in 1920, Aoudla still lives in Cape Dorset. His sculptural style, even in current works, is reminiscent of the simplicity and direct power of Inuit art from the 1950’s and 1960’s. Aoudla is particularly known for his depictions of the sea goddess, Senda. His late wife Nuluapik was also a sculptor.

Mark Pitseolak

Mark was born in Cape Dorset in 1945. He is the natural son of Etidlooie Etidlooie and the adopted son of Peter Pitseolak, the celebrated Inuit author, photographer and artist. Mark was married to Oopik Pitsiulak. The sculpture of Mark in this exhibition depicts the legent of Tiktaliktuk, the hero who was stranded on a spring ice flow and carried off to an island beyond Dorset. After some time, he was certain that he could not survive and built a cairn of stones in which he lay down to die. Just in time, he spotted some seals and was able to capture them. From their bladders he made a float and, with a paddle fashioned from scapular bones, was able to make his way home again.

Oopik Pitsiulak

Daughter of Tommie Manning and daughter-in-law of Peter Pitseolak, Oopik combines traditional women’s skill in beadwork with sculptural finesse. Born in Kimmirut in 1946, she has lived in Cape Dorset since 1960. She attended art courses at Nunavut Arctic College and has become an expert jewellery maker. Her work is included in several prominent public art collections. Oopik was featured in Inuit Women Artists and her work and motivation is explored in the accompanying exhibition catalogue. In her sculpture, she focuses primarily on images of women.

Paulassie Pootoogook

Paulassie was born in 1927 and is one of the acknowledged masters of contemporary Cape Dorset sculpture. He is the son of Pootoogook, the important camp leader, and his brothers, Salomonie, Pudlat, Kananginak and Eegyvudluk, are also well-known artists. His wife Ishuhungitok was a graphic artist.

May Qayuaryuk

Oviloo Tunnillie, Reclining Woman, ca. 1975, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Stone, 5 x 6 1/4 x 8 in.

Better Known by her alternate name, Kudjuakjuk, Mary was born in 1908 and died in 1982. She was married to Kopapik and is the mother of Qaunaq Mikkigak, Sheojuke Toonoo and Laisa Qayuaryuk. Mary was the first woman elected to the Cape Dorset Community Council, and she was involved in the drawing and printmaking programme at the Co-op from the very beginning. Her sculpture is recognizable for its simplified outlines and compact forms.

Kellypalik Oimirpik

Born in 1948, Kellypalik Qimirpik is a powerful sculptor of the middle generation of artists from Cape Dorset. He is a prolific sculptor, particularly known for his eccentric transformation subjects. His mos recent solo exhibition was held in Germany.

Saggiak

Saggiak was born in 1897 and died in 1980. His wife was Lizzie, the well-known graphic artist and tiehr son is Kumakuluk. Like Kiakshuk and Tudlik, Saggiak lived the traditional life for most of his adult years. His sculptures reflect traditional themes and, despite their simplified form, radiate a powerful presence. His work was featured in the Masterworks exhibition.

Kumakuluk Saggiak

Born in 1944, the son of Saggiak, Kumakuluk has lived both in the north and in southern Canada. He was one of the first Inuit artists to attend art school in the south, first in Maine and then in Toronto. Kumakuluk’s work is noted for technical excellence and imaginative realism. His favourite subjects are birds and fish. Kumakuluk was commissioned to create murals for the Canadian pavilion at Expo ’67 and bas-relief panels for the parliament buildings.

Sagiatuk Sagiatuk

Sagiatuk was born in 1932. He is married to Kakulu, the graphic artist. He was a Board Member of the Dorset Co-op in the 1990’s. In addition to producing his own artwork, Sagiatuk worked as a printer and cut the images into the stone blocks for the early printmaking programme. His precision and skill lends itself to the images of animals and birds for which he is known.

Pauta Saila

Pauta Saila was born in 1916 and is married to Pitaloosie Saila, the talented graphic artist. While he lived most of his life on the land in the traditional manner, he is also one of the first Inuit artists to gain widespread recognition in the south. Pauta has been active as a graphic artist since the early years of the Co-op, but is best known as a sculptor. He has attained international fame for his powerful depictions of bears. His work was featured in the Masterworks exhibition, in addition to numerous national and international shows.

Tudlik, Bear, 1967, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Stone, 4 x 4 1/4 x 2 in.

Eelee Simigak

Eelee was born in 1931 near Kimmirut and died in Cape Dorset. The sculpture by Eelee in this exhibition is made of stone from an unusual local deposit at a site on Baffin Island north of Kangia known as the ‘place where the thunder is’.

Tudlik

The father of Latcholassie Akesuk, Tudlik was born in 1890 and died in 1966. He was known both as a printmaker and a sculptor. His distinctive, simplified style resulted in sculptural creations which, despite their small size, are both powerful and monumental. Tudlik’s sculpture, highly sought-after by collectors, has been featured in numerous Inuit art publications, and was included in the Masterworks exhibition.

Oviloo Tunnillie

Oviloo was born in 1949 in Cape Dorset. She is the daughter of artists Toonoo and Sheojuke. She was inspired to carve by her father, whose death greatly affected her. Oviloo is famous for her compelling images of the female form, and frequently returns to the theme of the grieving woman. She has gained an international reputation for her powerful and innovative subject matter and form. Oviloo’s sculpture has been included in several catalogued exhibitions, including Inuit Women Artists.

Bibliographic References

Inuit Women Artists – Inuit Women Artists, Edited by Odette Leroux, Marion E. Jackson and Minnie Aodla Freeman, Exhibition catalogue. Ottawa: Canada. Museum of Civilization, 1994.

Masterworks – Canadian Eskimo Arts Council. Sculpture / Inuit: Sculpture of the Inuit: Masterworks of the Canadian Arctic. Exhibition catalogue. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971.