OWL’S BOUQUET, 2007, Stonecut & stencil, 24 1/2 x 30 in.

Exhibition opened October 17, 2023

“For my subject matter I don’t start off and pick a subject as such; that’s not my way of addressing a drawing. My way of doing it is to start without a preconceived plan of exactly what I am going to execute in full, and so I come up with a small part of it which is pleasing to me and I use that as a starting point to wander into, through the drawing. I try to make things that satisfy my eye, that satisfy my sense of form and colour.”

—Kenojuak Ashevak [1]

Foreword from Patricia Feheley

This exhibition features works by Kenojuak Ashevak from the esteemed Inuit Art Collection of John and Joyce Price. Over the years, it has been my honour and privilege to form a lasting friendship with John and Joyce, forged initially through our mutual passion for Inuit art. This was further honed by our shared close relationship with Kenojuak and celebrated through our personal adventures with her, both in her northern world and in our southern world. Coming from the largest private collection of Kenojuak’s works in the world, I am proud to present them in this exhibition. Masterfully created by the incomparable artist, and assembled with love by her good friends, John and Joyce.

Kenojuak Ashevak—how can one possibly describe this woman who gave so much to us all. She was incredibly accomplished: a Companion of the Order of Canada, holder of two honorary degrees, the subject of several books and films. None of this however can capture the true magic and the sparkle that was Kenojuak Ashevak.

Remarkably, she was among the first generation of Inuit to pursue drawing in the early 1960s. At this time the concept of an artist was foreign in the Arctic and no one knew exactly what that entailed. Kenojuak in fact defined this role, both for herself and others, by way of her hard work and incredible success as an Inuk artist.

Kenojuak’s first drawings were strong graphic images of her personal Arctic world. Her bold colour, strong silhouettes, and intertwined bird forms were revolutionary for her time—something that is difficult to remember now that these same forms have become emblems of Canadian art. Kenojuak’s constant willingness to experiment, to add printmaking to her skillset, to vary drawing media and scale, and finally: design a full-scale chapel window created in stained glass while in her late 70s.

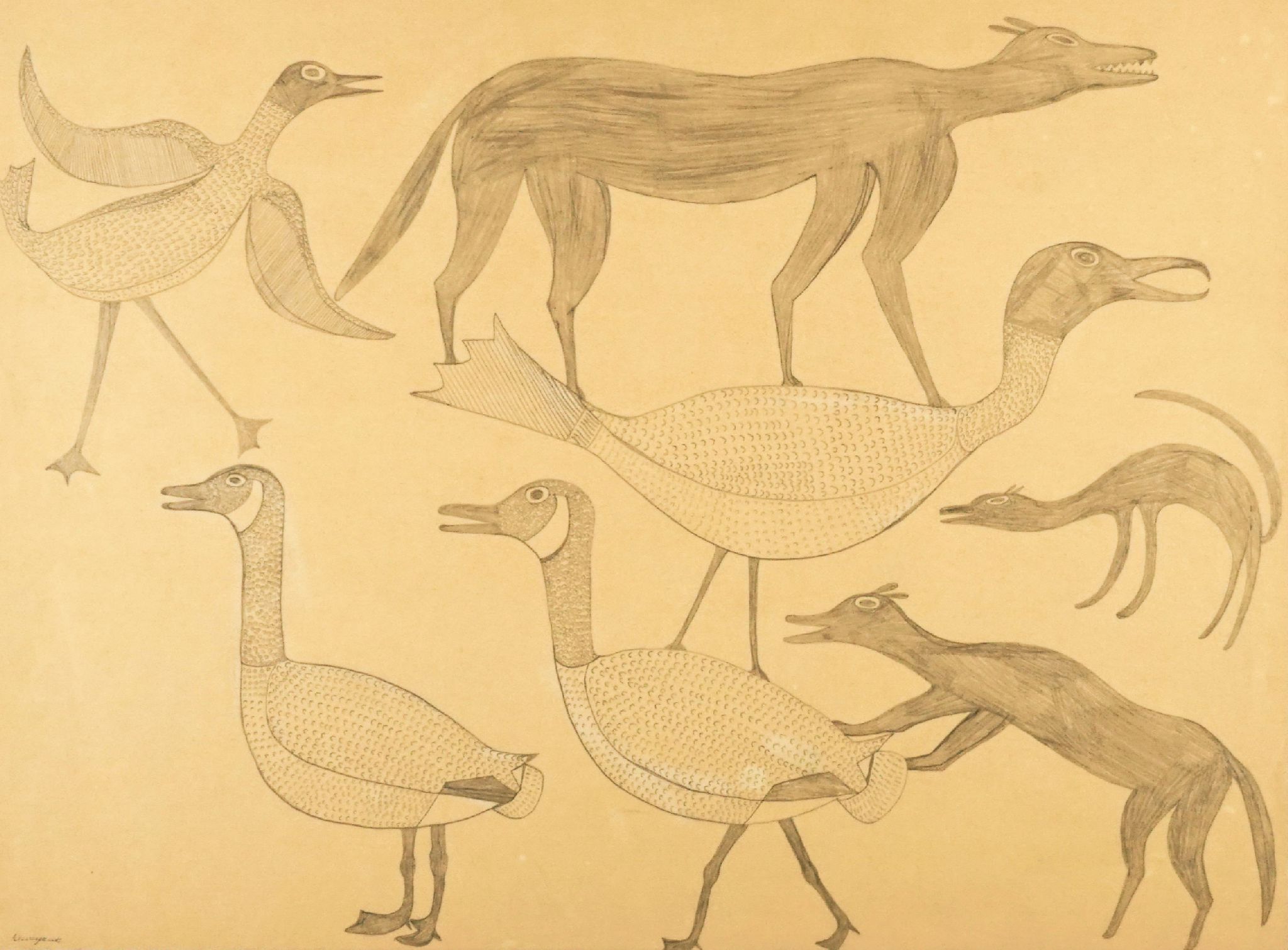

BIRDS AND WOLVES, 1960, Graphite, 18 x 24 in.

In her later years Kenojuak served as a mentor, reminding young aspiring artists in Kinngait that working on paper is hard. Her success inspired many of them to keep trying, and although the forms are different and time has passed, her influence lives on in the work of many contemporary Inuit artists producing today.

Those who were fortunate enough to know Kenojuak know the meaning of the sparkle. The sparkle was in her eyes and would light up her face, as well as the world around her. It is the same sparkle that leaps out from her work—that which encapsulated a great artist and talented and wonderful human being.

The Beginning: Drawing

Kenojuak Ashevak’s earliest ventures into graphic art were with sealskin applique designs made for garments. When given paper and asked to draw with a pencil in the late-1950s, Ashevak was told to draw what was in her mind, and she was initially reticent. Finding inspiration from visual storytelling, her early graphite drawings recalled the ethereal “shadow puppets” elders would create telling stories with their hands on the sides of igloos or tents, illuminated by the seal oil lamp. [2] Components of many of these early drawings went on to become prints.

As she continued, Ashevak began to use coloured wax crayon which emphasized the sure lines and intricate compositions of her graphite drawings. Then, with the advent of coloured pencils, in the mid-1960s her drawings transformed into symphonies of colour. Interestingly, Ashevak would choose her colours before deciding what to draw, as she stated, “I put out the colours that I want to use… But when I do go on and come up with the inspiration of something to put down, it’s still going to be set in the colours that I had set out for that drawing.” [3] Her emphasis on colour informed every drawing—a key element to the harmonious compositions that define her artistic legacy.

TWO BIRDS, 1975, Stone, 7 x 13 x 3 1/2 in.

Different Media: Sculpture, Metal, Glass

“Sculpture is so much easier than drawing, when you look at the stone and consider it, you can find what is there and then reveal it, while in drawing you have a blank paper and have to think up the image.” —Kenojuak Ashevak [4]

According to Jean Blodgett, Ashevak began making carvings in the late 1950s, many of which were likely attributed to her sculptor husband, Johnniebo Ashevak. [5] Through the 1960s and 1970s she developed a unique style of carving: self-contained, form-focused compositions. The sculpture Two Birds (c. 1968) [6] captures this personal style perfectly—the hugging birds exist within a triangular formation softened by the contours of their individual bodies. Her sculptures did not always feature birds, as transformations and works with multiple images also appeared.

Ashevak was enthusiastic about experimentation. During a brief period in the 1970s, the studios held jewelry workshops during which Ashevak created designs that resulted in exquisite broaches, pendants, and sculptures executed in different metals. With the encouragement of John and Joyce Price, she also created a three-dimensional glass sculpture of a bird at the Pilchuk Glass School in Washington State. Only two were made; Ashevak proudly displayed hers in her home in Kinngait, and the other remains in the Price Collection.

In 2004, Ashevak was commissioned to design a full-scale stained-glass window for the John Bell Chapel at Appleby College in Oakville, Ontario. Inspired by the chapel commission, Feheley Fine Arts commissioned an edition of six leaded stained-glass windows on a smaller scale. This glowing image is dominated by her signature owl surrounded by flowers and flanked by equally beautiful Arctic Char which she also captured in drawings.

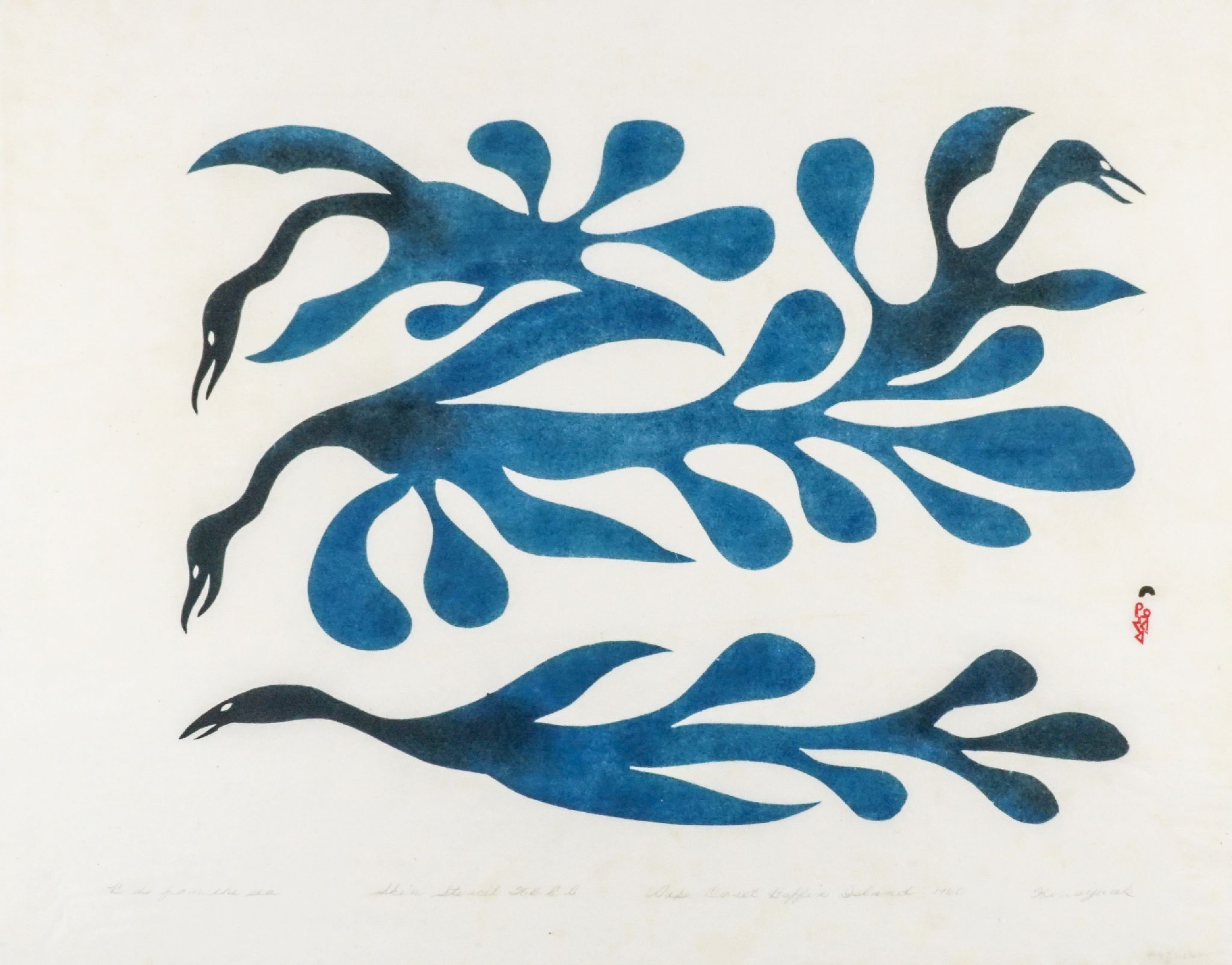

BIRDS FROM THE SEA, 1960, Stencil, 18 1/2 x 23 1/2 in.

Over a Lifetime: The Prints

The inaugural Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection included Ashevak’s first-ever print, Rabbit Eating Seaweed (1959), based on one of the artist’s early skin applique designs. The following year featured eleven of Ashevak’s prints in the collection, many evocative of her ethereal graphite drawings. One of these was the famous Enchanted Owl (1960), printed in both green and red iterations. [7] That same year, her print Birds from the Sea was released, reminscent of Rabbit Eating Seaweed and equally striking. With the exception of one year, printed images by Ashevak dominated the annual print collections until her death in 2013.

Initially, Ashevak’s images were translated by the studio printers using either the stonecut technique (relief printing), or stencil. Early on, Terry Ryan introduced etching and engraving. This process was more intensive as it involved using a printing press, but it prompted the artist to work directly on the printing plate, finally allowing the hand of the artist, not the printer, to create the lines. Ashevak flourished at this medium, creating intricate lines and surface textures which dismayed the printers—her images were the hardest to print!

Ashevak was at first suspicious of lithography, the new printing technique introduced in the mid-1970s. Similar to etching and engraving, the method allowed artists to draw directly onto the printing stone. She overcame her skepticism while creating the images for two print portfolios commissioned by UK-based Theo Waddington Galleries. These lithographs, created in 1979 and 1980, boasted bright colours and explosive compositions, resplendent with Ashevak’s love of colour.

Terry Ryan continued to introduce new techniques to challenge ambitious artists like Ashevak. In the early 1990s, a workshop by Paul Machnik of Studio PM introduced etching and aquatint, in which plates were etched in Kinngait then shipped south to Montreal where they editioned and embellished with aquatint, a technique likened to watercolour. Said John Western (Dorset Fine Arts) of the new method, “Studio PM has achieved a quality seen in very few other Inuit prints—a sense of the sublime.” [8] These were indeed sublime and brought out the best in Ashevak’s images.

SERPENTINE WOLF, 2013, Lithograph, 22 x 30 in.

The 1990s marked an increased interest in original drawings, which spurred several artists to develop their own unique styles. Ashevak’s drawings became increasingly bold with colour and intricate designs. While some recalled earlier images, others became progressively complex. The drawings of this decade signal a departure from the dominance of images by Ashevak produced by the print studios, to stunning original works of art.

A Burgeoning Artist

The new millennium found Ashevak as not only the most famous contemporary Inuk artist, but a Canadian icon and an international star. She was now travelling to the United States, Japan, and Europe for events and exhibitions, and was ready for her next challenge. Her collaboration with Paul Machnik led to one of her most exciting endeavors involving the technique of sugar lift printing. An exhausting undertaking, she created the matrices for two monumental prints: Tikiniq (2007), which encompassed six panels stretching a span of fifteen feet; and Angakuit Qaijut (Emerging Spirits) (2010), a nine-panelled masterpiece. To complete the works, Ashevak would wield squeeze bottles filled with an ink and sugar solution onto large plates. Paul Machnik recalls, “… in her eighties she was on her hands and knees doing a piece that was 26-feet in length without any complaints, and truly engaged.” [9]

Her other images completed in more traditional printing techniques took on a new sense of experimentation. Spotted Loon (2006) indicated a new approach to colour for the artist as vibrant blues and whites enlivened her signature red and black compositions. Her last signed print, Serpentine Wolf (2013), exemplifies this. It demonstrates a new take on an animal that had so often appeared in her drawings and prints. This wolf is bold and cheeky, sporting a brightly coloured body suit.

In her last years, Ashevak also created a series of rare, large-scale drawings. This was made possible by the availability of rolls of large paper which allowed artists to expand the size of their drawings. Filled with joyous colour, these simply provided a greater opportunity for Ashevak to celebrate the subjects that she loved to draw.

“I am grateful to those people who are interested in and admire my work. When I am dead, I am sure there will still be people discussing my art.”

—Kenojuak Ashevak [10]

Endnotes

[1] Blodgett, Jean, Grasp Tight the Old Ways, Art Gallery of Ontario, 1983 (Exhibition Catalogue), 92[2] See the opening credits for the film Eskimo Artist: Kenojuak (1964, National Film Board) directed by John Feeney. The third image to appear is in fact taken from the artist’s 1960 print Birds From the Sea.

[3] Jean Blodgett, Kenojuak (Toronto: Firefly, 1985), 41.

[4] From the artist in conversation with Pat Feheley while showing an unfinished sculpture and her carving tools, 1996.

[5] Jean Blodgett, Kenojuak (Toronto: Firefly, 1985), 67.

[6] Ibid, 70. Two Birds is reproduced with a later date.

[7] The Enchanted Owl edition was split; 25 were printed in black and red and 25 in green and red.

[8] John Westren, The Inuit Print, ed. Leslie Boyd (USA: Pomegranate, 2007), 242.

[9] Paul Machnik, “Remembering Kenojuak” Inuit Art Quarterly 27.1 (Winter 2014), 45.

[10] Jean Blodgett, Kenojuak (Toronto: Firefly, 1985), 24.

John and Joyce Price with Kenojuak Ashevak.

Note from John and Joyce Price

Over fifty years ago, we discovered Inuit art. While we did not realize it at the time, it would be the artists themselves that became of great importance to us. I (John) considered Kenojuak Ashevak to be like “my mother in the North,” and she thought of me like “her son in the South.” She visited our home in Seattle over four times, and our favourite moments with her were the family moments. We still recall our grandson Jay in her arms, then later as a toddler sitting next to her on the couch. We also loved picking apples with her in Eastern Washington and picking berries on Bainbridge Island. While we didn’t speak the same language, we always understood what the other was thinking through big smiles—we will never forget the look of amazement on Kenojuak’s face when hundreds of snowbirds flew over us at Skagit Valley.

We give thanks to former Studio Manager Jimmy Manning for his friendship and for being there with the artists and making sure that we could always communicate, despite living far away. Our love and appreciation will be with the Inuit and their art, forever.

— John and Joyce Price

To view available artworks by Kenojuak Ashevak, click here.