Kenojuak Ashevak, OWL WITH TWO BIRDS, 2004, coloured pencil & ink, 20 x 26 in.

Exhibition opened November 6, 2004

Generations Series

The very existence of our recurring ‘Generations’ series suggests a profound trend toward the artistic within Inuit families. Questions are tantalizing: Does artistic talent run in the blood, or is it culturally or socially determined? Why are there so many artists in a relatively small community such as Cape Dorset? Are there connecting threads between related artists of different generations, or does each branch of the family tree strain toward a new patch of sky? These issues and more are explored in this series.

Kenojuak & Onward

There is no more famous Inuit artist than Kenojuak Ashevak, the grande dame of Inuit graphics since the first Cape Dorset print release over forty years ago. Kenojuak has devoted more than half her life to art-making, and her fame now extends around the globe. She is a prolific and dedicated contemporary Canadian artist and an international ambassador for Inuit art.

Not surprisingly, there is an artistic ‘next generation’ on the rise in the Ashevak family. Two of Kenojuak’s sons, Adamie and Arnaqu, make their living as artists – each with a unique style and distinctive personality. Kenojuak, Adamie and Arnaqu are all aware of the others’ work, but each follows a separate vision. “I have watched my mother and my brother,” says Adamie. “Our arts are quite different – the way we work. My brother’s carvings are quite different from mine, and my mother’s work is so different.”

Kenojuak is glad to see the next generation making a living as artists as she has. “I think it is important for them to be able to create with their hands,” she says. “It is very important that they find what they can do in terms of art.” The traditional and the modern intersect in the works of these two generations of artists from the Ashevak family. Together, they embody the iconic and the innovative in Inuit art today and point onward to the future of the art form.

Kenojuak Ashevak

Kenojuak is undoubtedly the most acclaimed Inuit artist living today. Instantly recognizable, her artistic images have become emblems of Inuit art. Her career spans a half century, during which time she has made thousands of drawings, prints and sculptures, although she carves infrequently these days.

BIRD, ca. 1978, stone, 9.5 x 11 x 6 in.

Born in 1927 in an Inuit camp on southern Baffin Island, Kenojuak lived a traditional nomadic existence before settling in Cape Dorset with her family. She began participating in the graphics program in the early 1960s, quickly establishing herself as one of the most prolific and innovative artists of the time. “My work has changed quite a bit since I started,” she notes. “At first, it was just in pencil; there was no colour.” Perhaps discerning the suitability of fluidly outlined forms for use in stonecut printing in the carly years, Kenojuak developed a drawing style that emphasized the contrast between positive and negative space. Her symmetrically arranged birds with patterned plumage are still revered as superb examples of the classic Cape Dorset image.

Kenojuak is the recipient of two honorary doctorates and is the subject of several books and a film about her art and life. She is a Companion of the Order of Canada, member of the Royal Canadian Academy of artists, recipient of a Lifetime Aboriginal Achievement Award, and has a star on the Canadian Walk of Fame. She holds the distinction of being the artist of the highest priced Canadian print sold at auction to date, and in November 2004 she will become the first Inuit artist ever to have designed a stained glass window. We are thrilled to announce the completion of Kenojuaks first original stained glass window, a vibrant vision created for the Chapel of Appleby College in Ontario. Feheley Fine Arts was privileged to coordinate this project – the first commission of its kind for an Inuit artist.

For this spiritual setting, Kenojuak created an image of bounty, praising the munificence of nature. As a traditional Inuit woman who lived on the land for much of her early life, Kenojuaks spirituality is infused with thoughts of nature and survival: “I came up with the owl; the owl is always around – in summer, spring and in winter – and fish is a main source of food everywhere and in all seasons. Above is a star, and the purple flowers are a kind of flower that come out here in Cape Dorset in the spring time – the later part of June. Flowers of all kinds are very important in the environment.”

Initially uncertain about working in the medium of stained glass, Kenojuak visited the Dakville site in the spring of 2004 and became absorbed by the possibilities. “It Was really important for me to sce the building – the chapel – first, before I knew what to do for the window,” she recalls. “After that, I started to work on ideas: “I did many drawings as a sort of ‘homework’ before I worked on a large drawing at the actual size of the window.” Kenojuak explains. Several preliminary drawings of fish are included in this exhibition. “I was trying to get an idea of how fish would work best in a stained glass window. They are the kind of fish that people call lake trout – the char that doesn’t go down to the river, it stays in the lake.” These images are crisp and luminous, heralding new and fertile ground in Kenojuak’s imagery as she endeavours to capture the ethereal glow of lit glass in her new drawings.

Kenojuak is very aware of the honour of this first commission in stained glass, and is extremely proud of the final product. “It was challenging, but in my heart I wanted to do it,” she says. She is pleased to know that her work will reside in good company among the other stained glass windows of the chapel. “Now people who will go into the church will also see what I made – that it is coming from an Inuit person.” As a result of this collaboration, Kenojuak has become intrigued by the artistic potential of the medium of stained glass. A whole new stage in Kenojuak’s development as a multi-media artist will be marked by the forthcoming release, in a very limited edition, of a brilliant new silkscreen image of birds on etched and hand-blown glass.

Adamie Ashevak, PREACHER, 1999, stone, 13.5 x 8 x 7.5 in.

Kenojuak rarely sculpts these days, but has worked periodically with traditional hand tools to create compact, iconic images that recall the economical line of her drawings. “I have seen the changes happen from when people just carved with axes and files,” she points out. “The tools and the ideas are very different today,” Nevertheless, when she sculpts, Kenojuak chooses the traditional. “When I do my carvings, I don’t want to use power tools,” she has explained.” It’s very dusty when you do use them; they’re very dangerous and may cause some physical damage. Plus, I like taking my time. Patience pays off and the form is the outcome.

Kenojuak’s graphics are filled with birds as well as human images and some mythological subjects such as Sedna. Her recent works on paper are increasingly dynamic and luminous compositions, featuring fish or rhythmic groupings of animals arranged on a white ground or amid vibrant Arctic landscapes. “Today, I am working with whatever colour I want, and it is magnificent,” she asserts. Her graphics are seldom narrative, rather they are formal explorations of colour, structure and detail brought to life under Kenojuak’s confident hand.

Adamie Ashevak

Adamie Ashevak acknowledges the influence of his mother Kenojuak, and father, artist Johnniebo Ashevak (now deceased) in his early development as an artist. Adamie was born in 1959 and began carving when he was only ten years old. “I guess I was watching my parents all the time,” he recalls,” so I probably learned from them.”

Today Adamie has carved a niche for himself among Cape Dorset artists, creating commanding sculptures of animals. Whereas Kenojuak’s signature subject has always been the bird, her son Adamie chooses the bear as the conduit for his creative energy. “I like polar bears so much. I like to watch them; he explains. “Every time when we are boating and we see a bear, I try to get closer to them.” In addition to this type of nature study, Adamie credits Nuna Parr with providing practical tips on the sculpting of bears during his formative years.

Like his mother before him, Adamie’s art eschews narrative or social commentary in favour of more formal artistic concerns. He conjures massive, fluid figures from hard stone by working with modern power tools that have greatly expanded his technical possibilities. Adamie works faster and on a larger scale than his mother could ever manage with hand tools, achieving daring compositional feats that add to the powerful realism of his subjects.

Arnaqu Ashevak

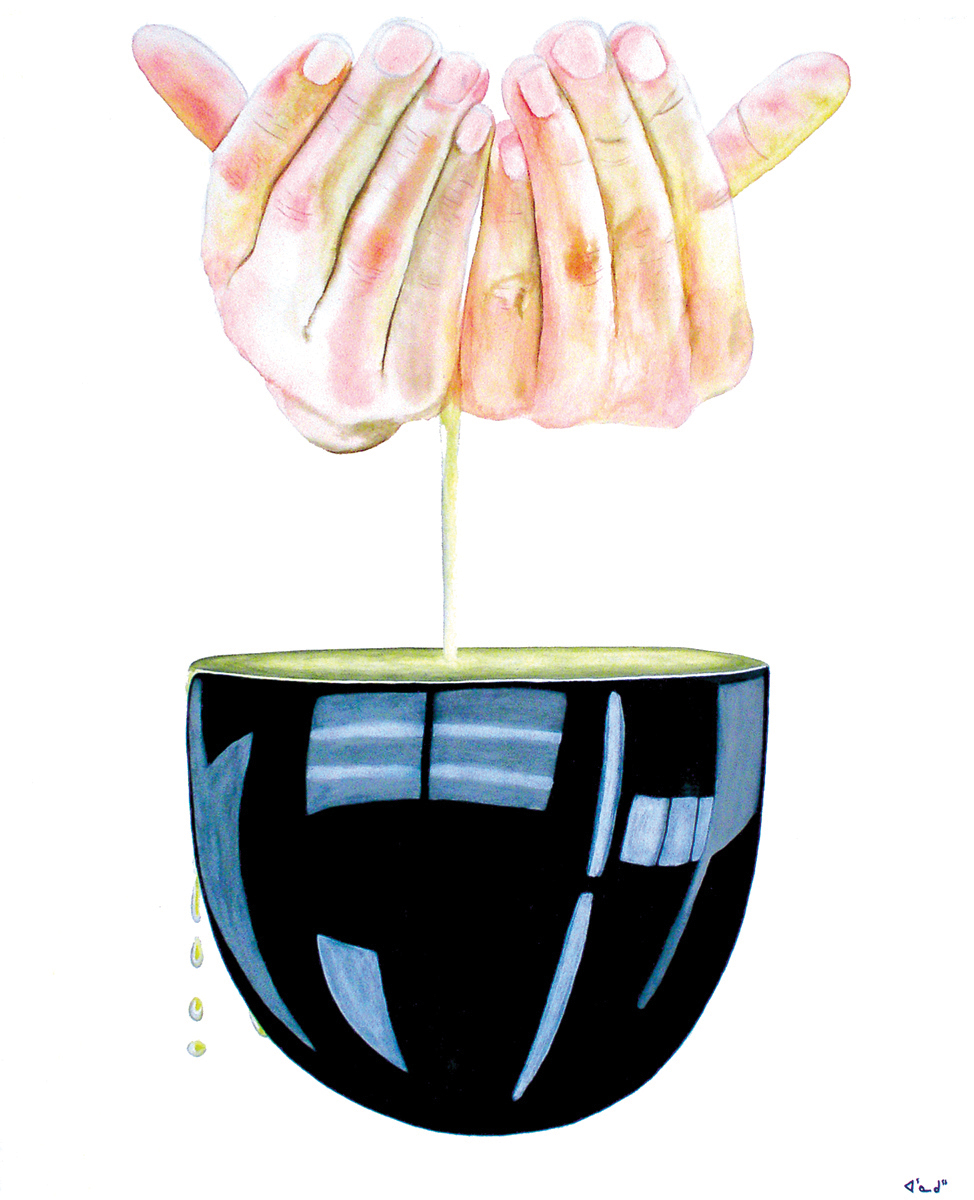

Arnaqu Ashevak, MISIGARQ (RENDERED OIL), 2002, watercolour, 44.5 x 36.25 in.

Arnaqu Ashevak belongs to a select group of younger generation Inuit artists who are successfully crossing over into the broader contemporary Canadian art market. He is a gifted and eloquent man creating fully modern artworks that challenge long-standing preconceptions about Inuit art while opening new doors for the future of the art form

Born in 1956 in an outpost camp on the land, Arnaqu Ashevak is the adopted son of Kenojuak and Johnniebo Ashevak. He has made his living as a sculptor in Cape Dorset since the early 1980s, although his first carvings were created earlier under the direction of Iqaluit high school art instructor Henry Evaluardjuk. “I was not influenced to be an artist by my family,” Arnaqu insists. “I didn’t know exactly what my mother was doing; she was making a living. That’s all I knew.” These days, Arnaqu creates sculptures and drawings, as well as prints that have been included in the annual Cape Dorset release since 1994. He has rapidly gained respect and renown for his arresting and distinctive works of art in various media.

Arnaqu’s sculpture is delicate and whimsical – two adjectives not generally associated with Inuit carving. His images of fragile flowers are extraordinary sculptural creations, meticulously assembled from small segments of stone and antler with metal pegging. These still life constructions are realistic in subject matter but symbolist in essence, and entirely unique among the work of his contemporaries. Like his brother, Arnaqu benefits from the technical advantages of modern power tools, yet their works in stone are fundamentally different in theme and conception.

Arnaqu’s original drawings and paintings on paper are often surprising and spontaneous creations, reminiscent of diary entries or mental snapshots that reflect the varied experience of any given day. In a thoroughly modern manner, the artist deftly switches media to better articulate his individual messages in colour or monotone, edgy line or inky silhouette.

Television is an eye that has opened new worlds for Arnaqu, resulting in varied imagery that can only be loosely defined as humanist in tone. A documentary program about the holocaust prompts a waking nightmare image. A video about Nuliajuk, the Inuit goddess also known as Sedna, spawns incarnations of the ‘birdman’ who takes human form to be her partner. Imagery plucked from art history books blends with ancient Inuit references as the artist overlays form and meaning. Arnaqu’s concern with the world beyond his Arctic settlement suffuses his work, distinguishing him as an emerging cultural and political observer with a sensitive and significant perspective.