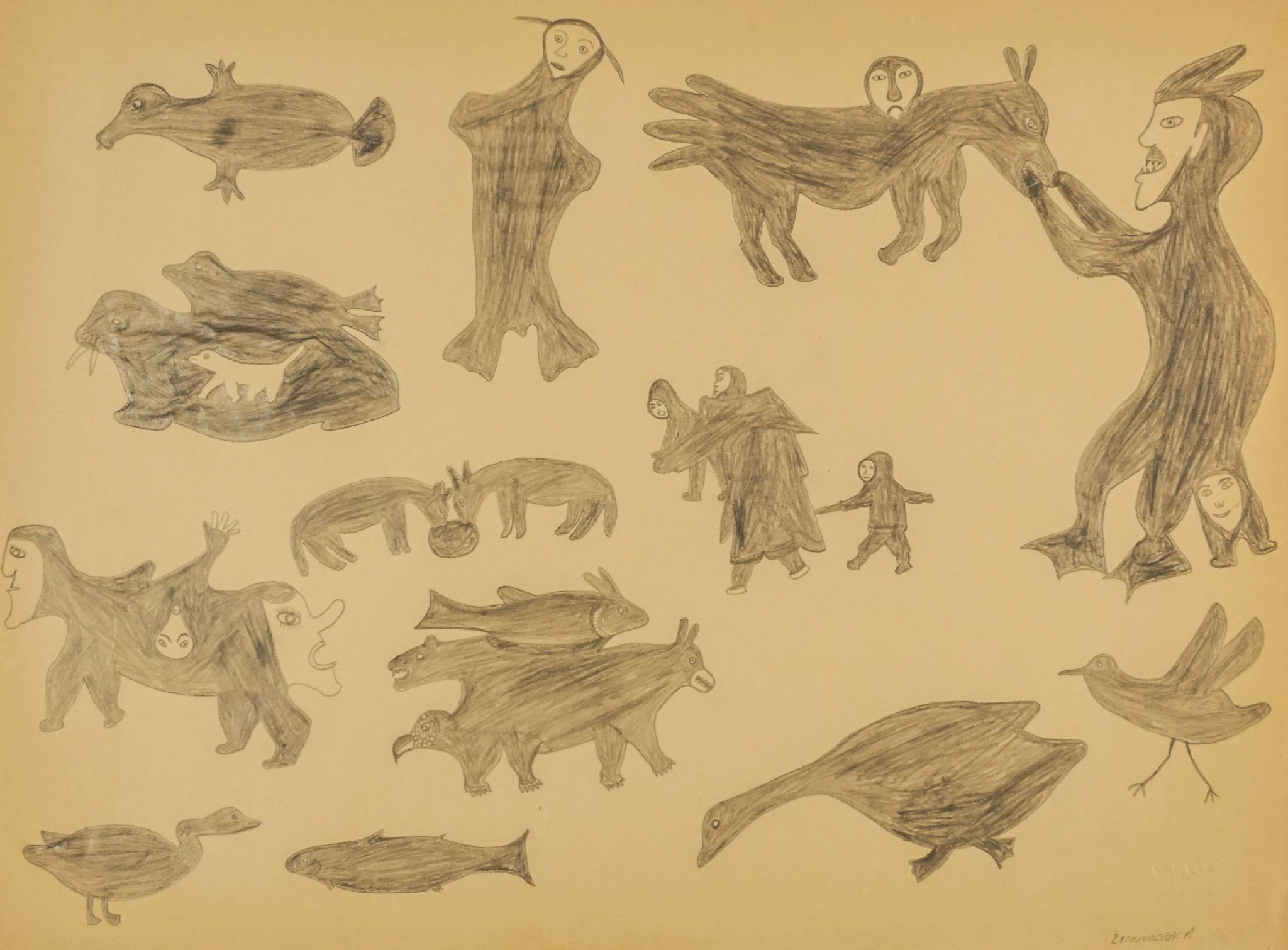

Eegyvudluk Ragee, COMPOSITION (TRANSFORMATIONS), c. 1960, Graphite, 18 x 24 1/8 in.

Exhibition opened March 16, 2023

Thirty years ago, almost to the day, the seminal exhibition Strange Scenes: Early Cape Dorset Drawings opened at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario. Curated by Susan Gustavison and Jean Blodgett, the show marked the first public exhibition that placed a focus on the early graphite drawings of the late-1950s and early-1960s. Blodgett explained that the “strange scenes” depicted were abundantly prevalent in not only in early Kinngait drawings, but also sculpture. [1] These scenes were considered strange because they evaded any imagery familiar in the Western tradition of artmaking—transformative figures, animals, and unidentifiable beings were, and continue to be, shockingly compelling to a Southern audience. Most of the artists were trying their hand at drawing for the very first time and though now over 60 years old, the drawings remain strikingly contemporary today.

Graphite features a curated selection of 23 early drawings from Kinngait that celebrate the incredible images created by the community’s very first artists—some of whom who remain unidentified and others who went on to pursue illustrious careers. It also pays homage the 30th anniversary of Strange Scenes which first spotlighted the early drawings and their charm, wit, and imagination, and paved the way for an appreciation of these foundational works.

Notably, the drawings in Graphite were completed during a time of transition. Inuit from around the Kinngait area were moving into the settlement from outpost camps, and the Kinngait Studios had been recently established at the community co-op. The studio encouraged locals to try art-making to make an income in a young community where few jobs existed. While drawings were largely produced to hopefully become prints in the early decades, this was not always the case during the formative years. Rather, most were experimental, as the graphite pencil operated as a vehicle through which images from the mind were transferred to paper. The logistics of the early drawings was incredible. Most were made outside the studio at home or out at camp, in the iglu (snow house) or qaumaq (sod house/tent). Women were known draw when the children were sleeping, then transport the drawings back to the studio rolled up in their amautiq (mother’s parka). Sometimes drawings would travel back by qamutik (sled) and artists were provided with tubes to protect them. Drawings would arrive in all sorts of conditions; coffee and cigarette smoke stains were common, as were roll marks.

Stories of shaman transformation and legendary creatures that were passed down across generations are thought to have had profound influence on the “strange scenes” of the early drawings. But as former Studio Manager Terry Ryan explained in 1992 (which reigns true to this day), interpretations are not so straightforward. Many works, rather in part, can be attributed to the experimental exercise of drawing, which then resulted in extraordinary works of art: “There are things depicted that we still don’t understand; in fact, I’m not sure that anyone understands them anymore. Certainly some of the drawings must depict these traditional beliefs. However […] many of the images are just an extension of the pencil.” [2]

Sources

[1] Jean Blodgett and Susan Gustavison, Strange Scenes: Early Cape Dorset Drawings (Kleinburg: McMichael Canadian Art Collection, 1993), 7. Strange Scenes was also the title of a print by Kiakshuk from 1964. [2] Ibid, 14.