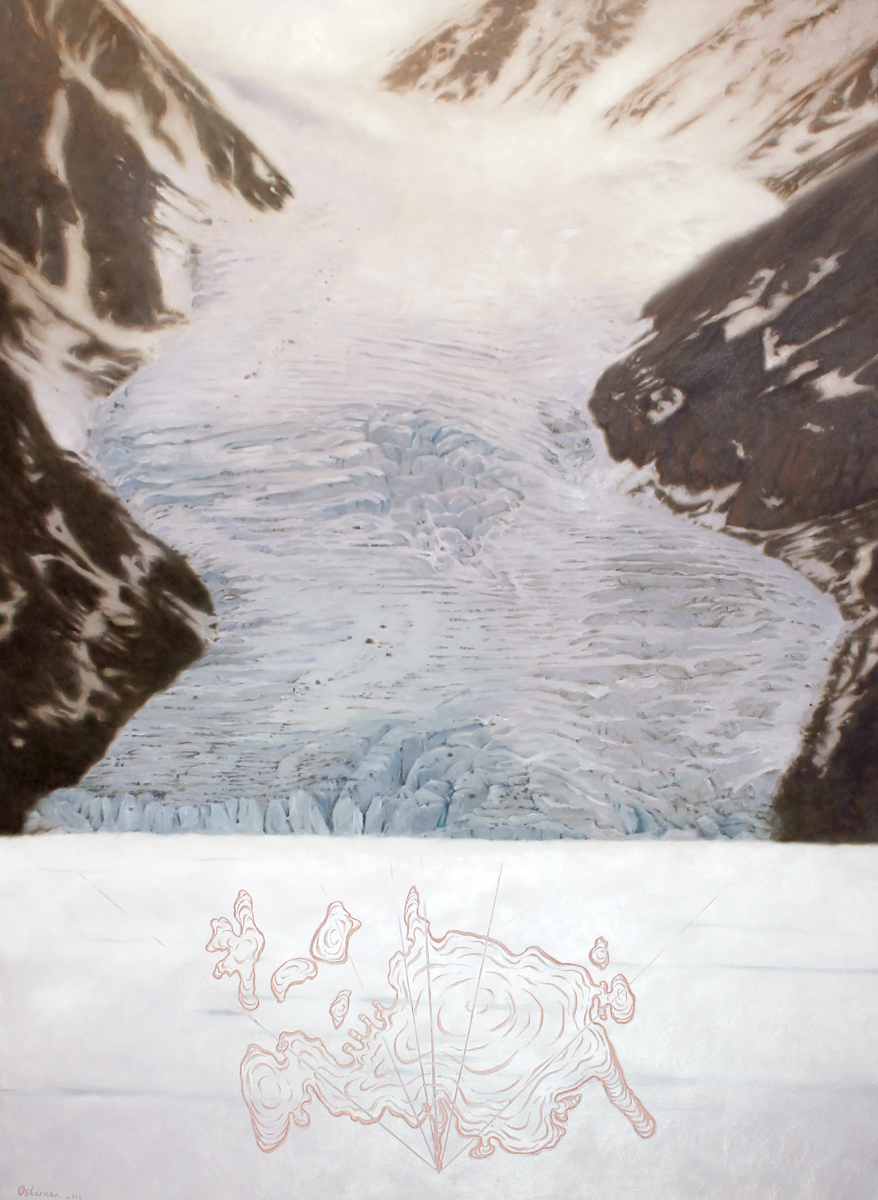

Danny Osborne, DANNY’S GLACIER. N76031W82014’, Oil on canvas, 48 x 36 in.

I didn’t meet Danny Osborne until January of this year. I was on a research trip to Iqaluit and it was my first time in Nunavut. The deep impact that the land has on Osborne’s practice was clear from the moment I set foot in his studio. With a panoramic view out to the frozen sea, the studio’s high walls were filled with paintings. Together a theme started to emerge, that of the Arctic, and how the region is represented, historicized, and mapped now and in the past. Moreover, Osborne’s paintings are about how the Arctic is experienced, and how he situates his place within it.

Osborne moved with his wife and children to Grise Fjord, the northernmost settlement in the Western Hemisphere in the late 1980s. The family spent their first few months in complete darkness, getting by with a dog team, the generosity of their neighbors and sheer tenacity. They have lived in the north ever since gaining first-hand knowledge of a place that the rest of the world only encounters through books, in photographs and in film, and through the masterful drawings, prints and sculptures of Inuit artists.

Unlike conventional representations of the Arctic, what makes Osborne’s paintings different is his intimate knowledge of this place. These paintings mark the artist’s return to Ellesmere Island near Grise Fiord and Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island. The works are made in a traditional manner; much like the plein air painters of decades past, they are based on first hand observation. He first paints the icebergs and glaciers in the field by trekking out to the base of the frozen monuments by snowmachine and on foot. In this environment his chosen medium, oil paint, is a practical choice; acrylics would freeze almost instantly here. Through this familiarity with his subject, Osborne’s images capture what the usual representations of the Arctic leave out—they arrest something of the beauty and mystique of these towering forms and they do so in a way that lends them a kind of luminosity or inner light. I take this illumination as a metaphor, something that philosopher Walter Benjamin equates with historical knowledge.

Osborne locates the icebergs and glaciers by the inclusion of topographical maps. As a means of underscoring this locative gesture, coordinates are also cited in their titles. This act links these places to the history of exploration that characterized the region. (Osborne has stated that he likes the idea that the works themselves could potentially function as maps—“that someone would be able to find their way around by using one of the paintings”). Some of his landscapes collapse nearly 100 miles of coastline into a single image, in doing so they trace a journey. For Osborne, this body of work reconciles how the first Europeans encountered this region; explorers like Martin Frobisher who searched in vain for a route through the Northwest Passage. In 1577, Frobisher claimed this part of the world on behalf of Queen Elizabeth I. It was named Meta Incognita (of limits unknown). Osborne’s paintings point to Frobisher’s limited comprehension of this place. These are not non-sites, but places that have names, places that are known. Danny Osborne might just be the best undiscovered artist working in Canada.

Candice Hopkins. May 2013

About the artist:

Danny Osborne was born in England but moved to Ireland in 1971 after finishing art school. Later, he lived with his young family in Grise Fiord, and then moved to Iqaluit in 2001. For the past 35 years much of his work has been done in Nunavut but mainly exhibited in Europe.

Danny loves working in a wide range of materials and has had fourteen solo shows.

He is included in many major public collections such as the Irish Museum of Modern Art. One of his better known works is the Oscar Wilde Memorial situated across from the National Gallery in Dublin, and he has painted four official ‘Speakers of the House’ portraits in the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut.

The critic, Aidan Dunne writes that “Osborne has a meticulous technique that is very much in the service of equally meticulous observation. He has an undiminished wonder at the way things are.”