Pudlo Pudlat, Senda, 1962, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Stone 6 x 9 x 9 1/2 in.

Foreword by Terry Ryan

My recollections of Cape Dorset during the notable decade of the 1960s unlike the frenetic sixties here in the Southern Hemisphere, was of a place only slowly awakening from a long period of relative tranquility.

Our Federal Government of that time had only recently shown an expressed interest in things north of 60 degrees, and the recommendations of their few field officers had started to slowly take hold. Transportation was still for the most part by summer icebreakers; airfields were few and far apart, and small aircraft, particularly in the eastern Arctic, a novelty. Commerce was, with the exception of a failing fur trade, non-existent.

Teachers, nurses, police officers and assorted government bureaucrats were slowly making their presence felt. The Inuit of the day (“Eskimos”) were for the most part still living ‘on the land’ and the communities (Trading Posts) were small and isolated. The Hudson’s Bay Company was reluctantly showing signs of giving up their place at the top of the totem. The new government bureaucracy, flexing their financial muscle, introduced programs, building and budgets, meagre as they were. And from these budgets arose a unique interest in the arts of the Inuit.

Dorset in particular was singled out for experimentation in arts and crafts development. This was a result of the support for and enthusiasm of, the local Government Field Officer, Jim Houston, and a group of kindred souls in the Ottawa bureaucracy. Stone carving was encouraged; printmaking was still in its infancy, as were other attempts at craft-related endeavours. From all this support came a truly wonderful response. Men and women responded enthusiastically to this opportunity, prompted only in part by the financial reward. Patriarchs such as Kiakshuk, Pudlo, Parr, Tudlik and Sheokjuk, along with many others, took up this newfound means of expression, proud of their culture and keen to show we kablunas their world.

Aqjangajuk Shaa, STANDING WALRUS, ca. 1965, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Stone, antler, 16 x 14 1/2 x 5 in.

For the most part, throughout the sixties, sculpture was small in scale and passionate in expression. There had not yet arisen the need to rush any aspect of life. Time was taken to complete, with the simplest of tools, truly eloquent and tactile images of those animals that occupied their dreams and provided their sustenance. Women and children were depicted with loving care, as were all manner of other daily activities. Hunting scenes were executed with a desire to communicate pride and prowess.

These subjects were also depicted in graphic form, either in drawing, an activity taken up by many, or in prints produced in the new co-op print shop. While some individuals preferred to work only in stone, others chose graphite on paper. Some found success in all and any materials; several drifted away from the program over time.

Life went on in many respects as it had for generations past. Hunting remained a daily constant in spite of a changing lifestyle of diminishing camp life being rapidly replaced by the new ‘settlement life’. The arts continued to expand. Printmaking was refined; experimentation with weaving, fabric printing, pottery and jewellery grew.

A new generation of men and women were offered an opportunity to be as creative as their elders. From this group emerged artists now internationally acclaimed for their talent. Men and women related by family or adoption effortlessly shared creative impulses and enthusiasm. Notable among these is the Ashoona family of artists: the matriarch Pitseolak, her daughter Napatchie and her sons Qaqaq, Koomwartok and Kiawak.

It is unlikely that we shall ever see a return to such a tranquil time in the Arctic. Forty years have passed ; a new and engaging group of talented artists has captured our eye, and new challenges face both them and our new Nunavut government.

The sixties were a time for initiation, reflective of a period filled with change and hope. As ensuing events have challenged and strengthen the Inuit in ways they could not have imagined then, the arts have sustained them.

The content that was so evident in those early small sculptures, drawings and prints has evolved into a new perception. It is perhaps with nostalgia that we regret the pasing of an era reflected in those little gems – a decade that started with the awakening of our responsibilities and their expectations. That decade ended with the death of the remarkable elder and artist, Parr, in 1969.

In that same year we watched a man on the moon – a truly outstanding undertaking from our southern point of view. For the Inuit, however, who believed the Shaman had undertaken the same journey many times before, it was less of an accomplishment. Discovering a means of artistic expression to enable communication with those people living beyond their borders was the true wonder.

May, 2001

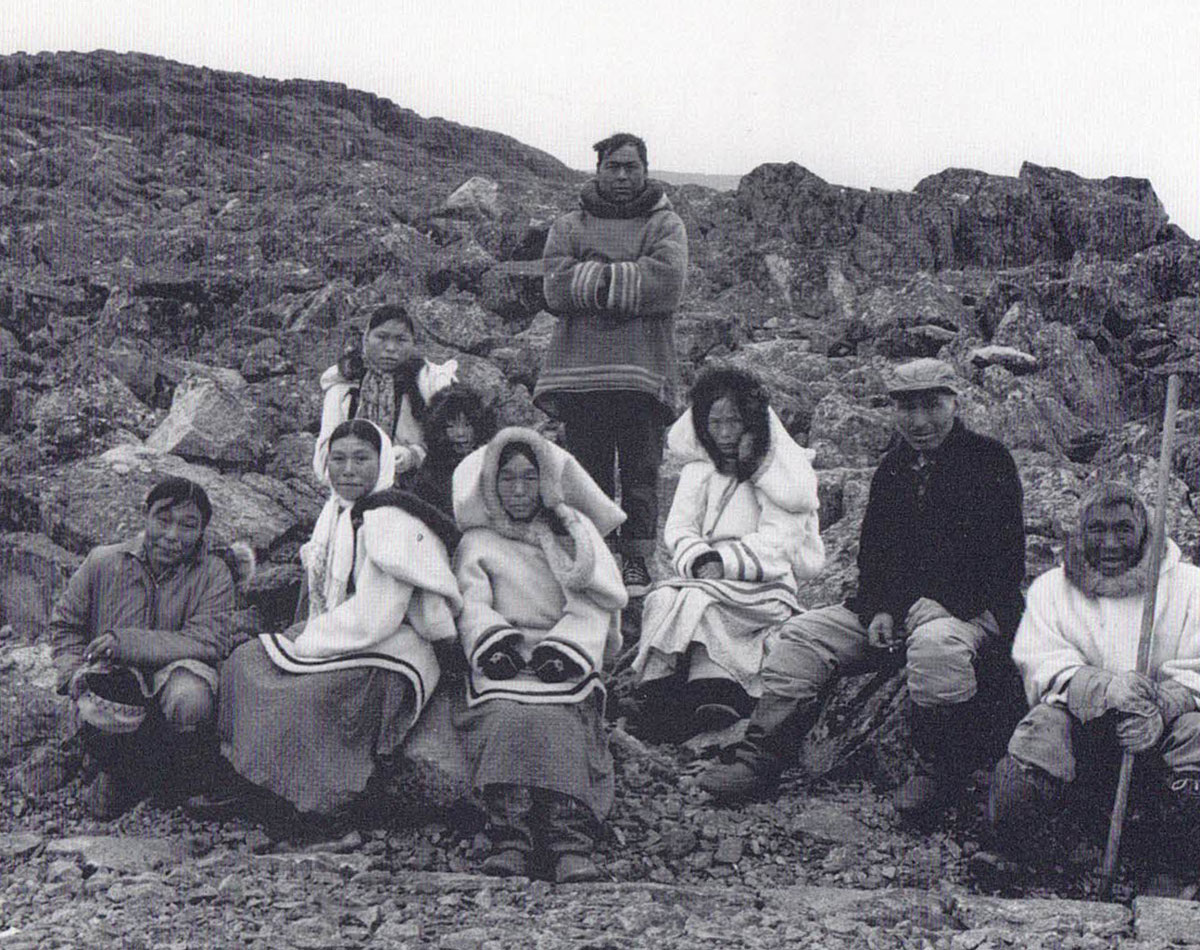

From left: Eegyvudluk Ragee, Kenojuak Ashevak, Napatchie Pootoogook with her son, Goo, Lucy Qinnuayuak, Pudlo Pudlat, Pitseolak Ashoona, Kiakshuk, Parr. Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 1961

Cape Dorset in the 1960s

The world is already familiar with the fame of the Cape Dorset artists from the 1960s. Still, questions surface: Why were these artists so successful? Why then? How were so many great talents uncovered in such a short time, from such a small population?

The seeds of all the subsequent success of Cape Dorset art were sewn during the formative years of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative. Everything created in this settlement over the last half-century, which has been so universally admired, is the product of the unique environment of Cape Dorset in the 1960s. At once entirely Inuit, these sculptures and graphics often seem to transcend time, place and culture. Perhaps they speak to us this clearly because they hover so close to the ideal of art as pure concept, unencumbered by formal teaching and traditional western art theory. The first experimental prints were made in 1957-58, following a legendary discussion between James Huston and Osuitok Ipeelee which proved the spark. Translating ancient graphic impulses and techniques of scrimshaw on ivory, the earliest printmakers transferred their thoughts to paper for the first time.

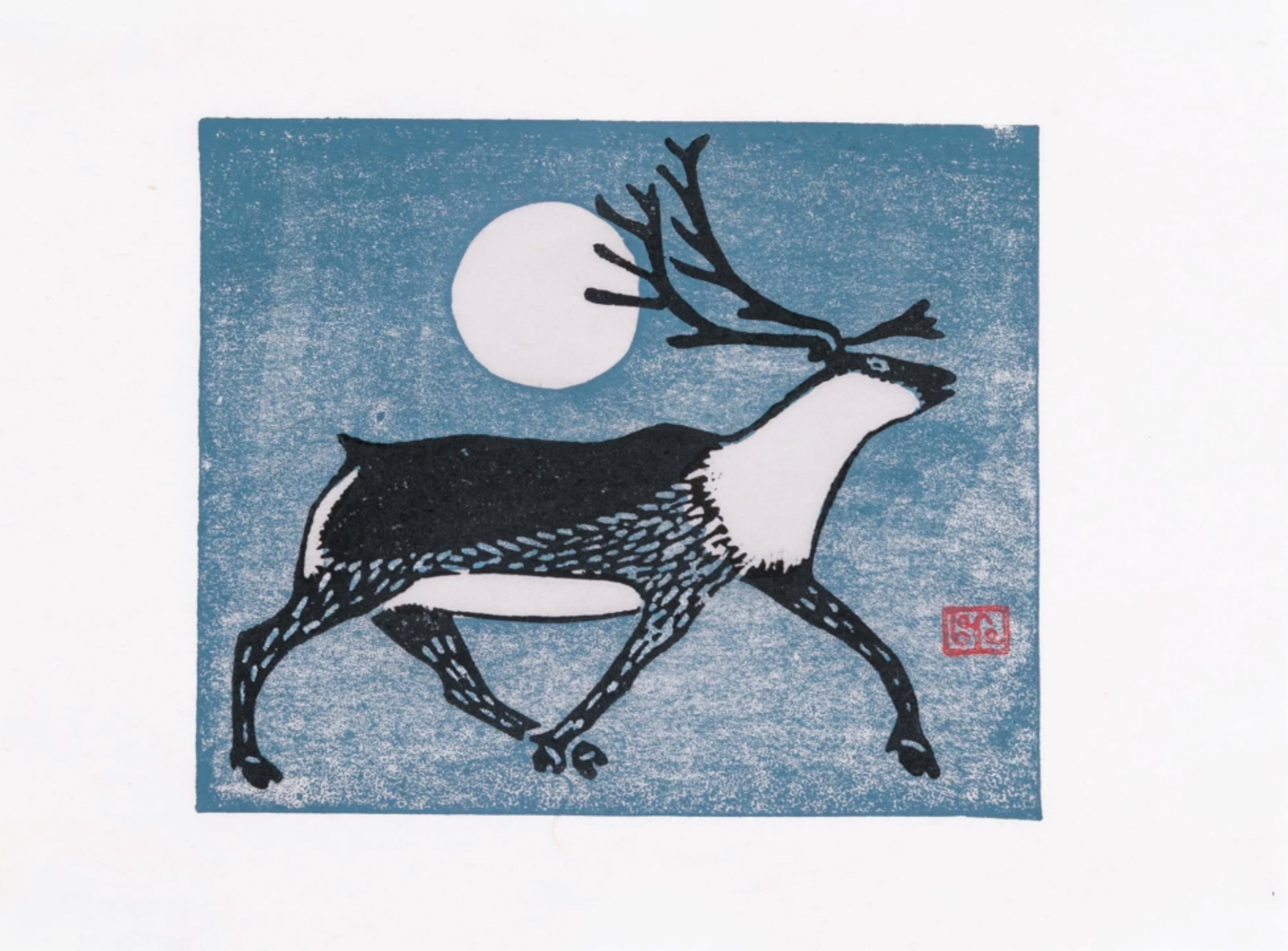

Kananginak Pootoogook, RUNNING CARIBOU, 1958, Stonect, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 6 x 8 in.

“At first we used just black ink but later we progressed to using different colours, using waxed paper. Whenever the prints were good e were happy and Shaumirk (James Houston) would actually dance for joy. …We also tried using small pieces of soapstone to see if it was better than linoleum, and so we made our first prints on stone. First of all we would colour the background and then use black ink on top of this. We did a stone picture of a caribou.”

–Kananginak Pootoogook, from the Foreword to the 1973 Dorset print catalogue

Two revered elders, Kiakshuk and Pootoogook, threw their support behind the early Cape Dorset print project. Four young men quickly stepped forward to learn and carry out the technical processes of printmaking: Iyola Kingwatsiak, Lukta Qiatsuk, Kananginak and his brother, Eegyvudluk Pootoogook. These men were all artists as well as technicians, creating their own carvings and drawings as well as printing the images of others.

Kiakshuk, KIKQAVIK AND THE HUNTER, 1960/69, Stonecut, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 24 x 28 in.

Lukta carefully cut the stone and printed his father’s image.

Tudlik, EXCITED MAN FORGETS HIS WEAPON, 1959, stonecut, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 12 x 18 in.

The 1959 print collection featured images by now-legendary figures like Niviaksiak, Tudlik and Kenojuak.

Kananginak Pootoogook, THREE SHOREBIRDS, 1969, Stonecut, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 18 x 22 in.

Following the success of the first Cape Dorset print collection of 1959, a co-operative was formed to facilitate the onroing arts projects. The original documents of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative were signed by the founding members: Kananginak Pootoogook, Iyola Kingwatsiak, Joanassie Salomonie, Lukta Qiatsuk and Kiakshuk. Osuitok Ipeelee was added as a signing member shortly thereafter. Kananginak was elected President of the Board of Directors, and the new arts advisor, Terry Ryan, was named Secretary of the Board.

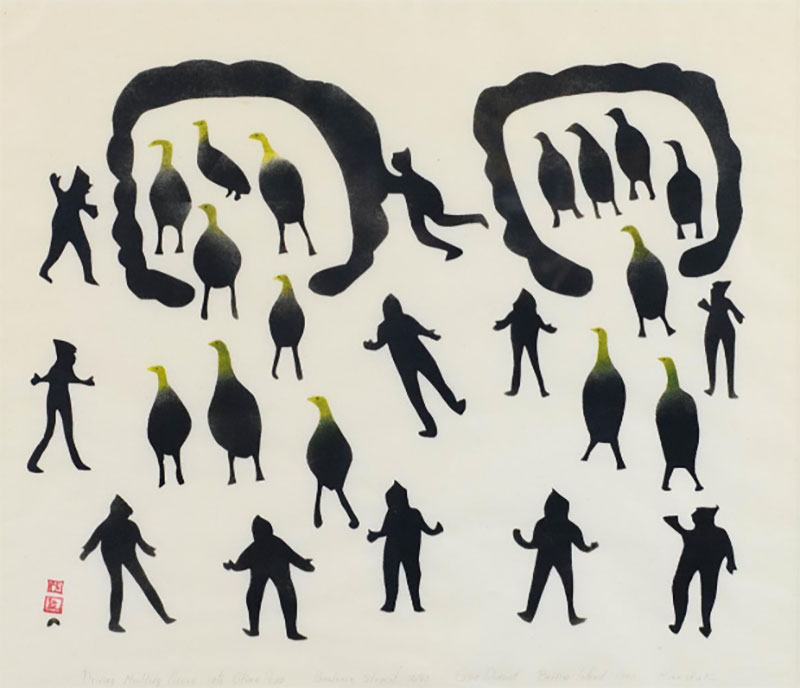

Kiakshuk, DRIVING MOULTING GEESE INTO THE STONE PENS, 1960, Stencil, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 19 1/2 x 23 3/4 in.

In 1960, many more names joined the roster in the print collection catalogue, including Sheouak, Kiakshuk and Pitseolak. From 1961 onward, new stars were introduced, such as Pudlo, Lucy and Parr.

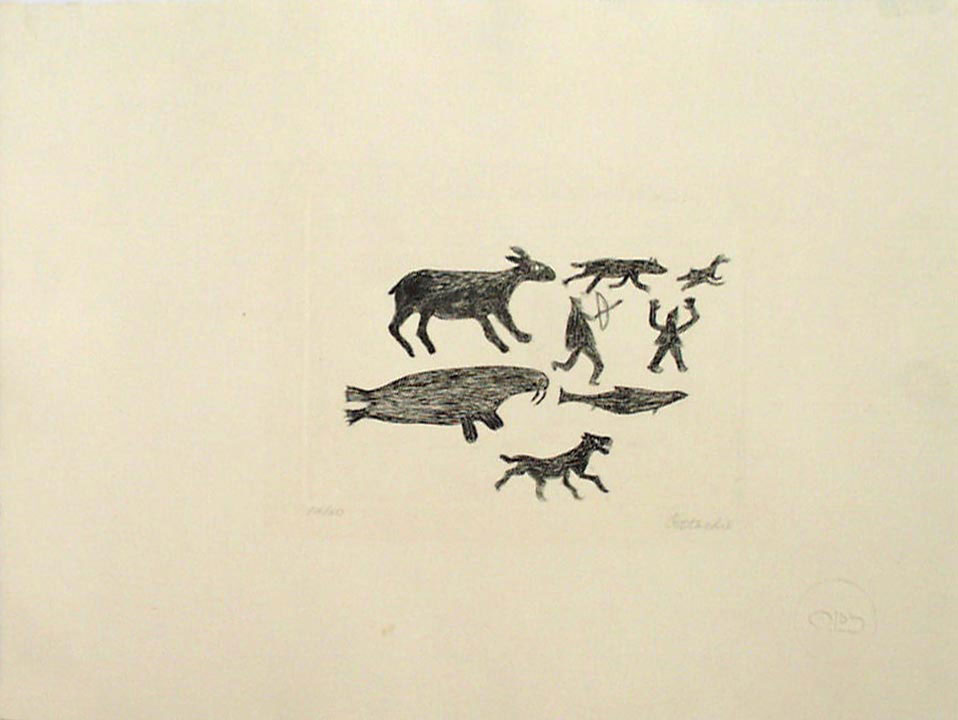

TImothy Ottochie, UNTITLED (HUNTING ANIMALS), 1962, Engraving, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 9 1/2 x 13 in.

The printmakers were among the first individuals to experiment with the technique of engraving images on copper plates. The results were unveiled in the 1962 collection. Timothy Ottochie joined the print makers in 1961, and worked on more than 300 prints over the next twenty years, in addition to printing his own engravings. The early engravings are among the freshest and most immediate expressions of creativity captured in print form.

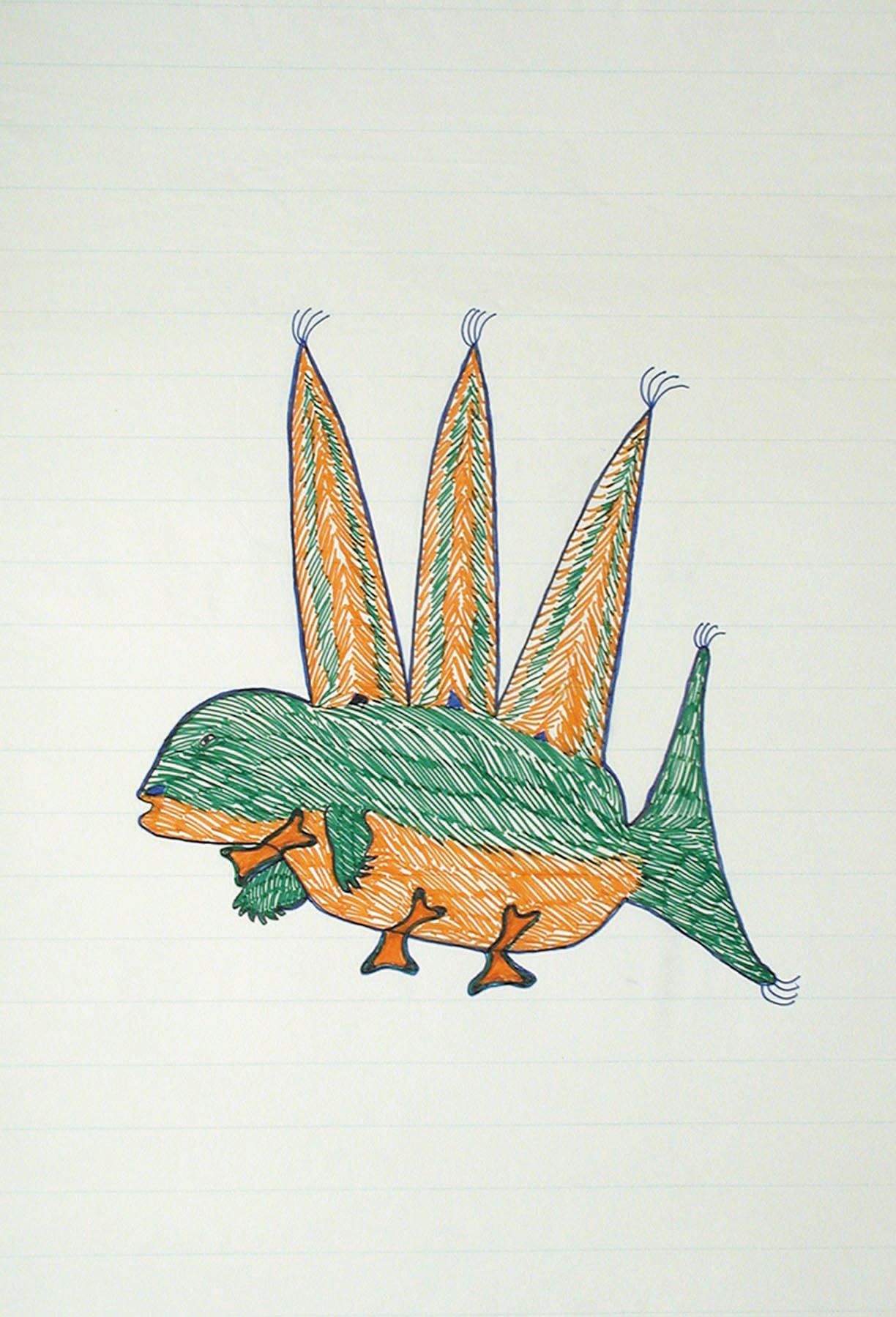

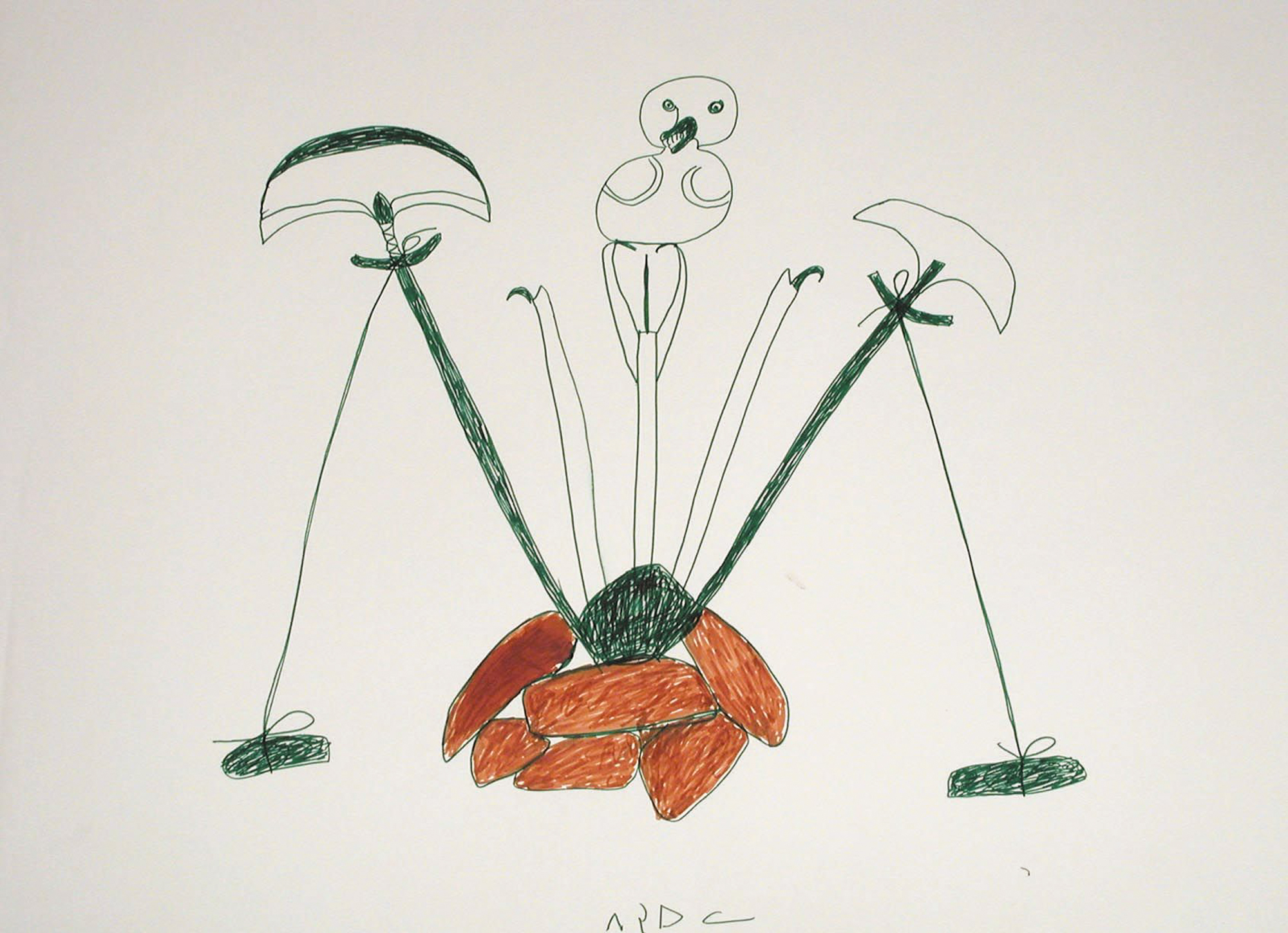

Pitseolak Ashoona, COMPOSITION (FISH CREATURE), 1966, Pentel, 24 x 18 in.

Everyone was encouraged to make drawings on paper to provide images for the early prints. Although almost no one had tried before, most of the men and women, when approached by Terry Ryan, were willing to try. The results were immediate. The Inuit embraced these foreign flat white sheets of paper and poured onto them images, fully-formed and spectacular, of spirits, animals, and the minutiae of daily life. When drawing paper was in short-supply, Terry Ryan recalls that artists would bring in drawings on any available substitutes. In this case, Pitseolak used a large sheet of ruled school paper.

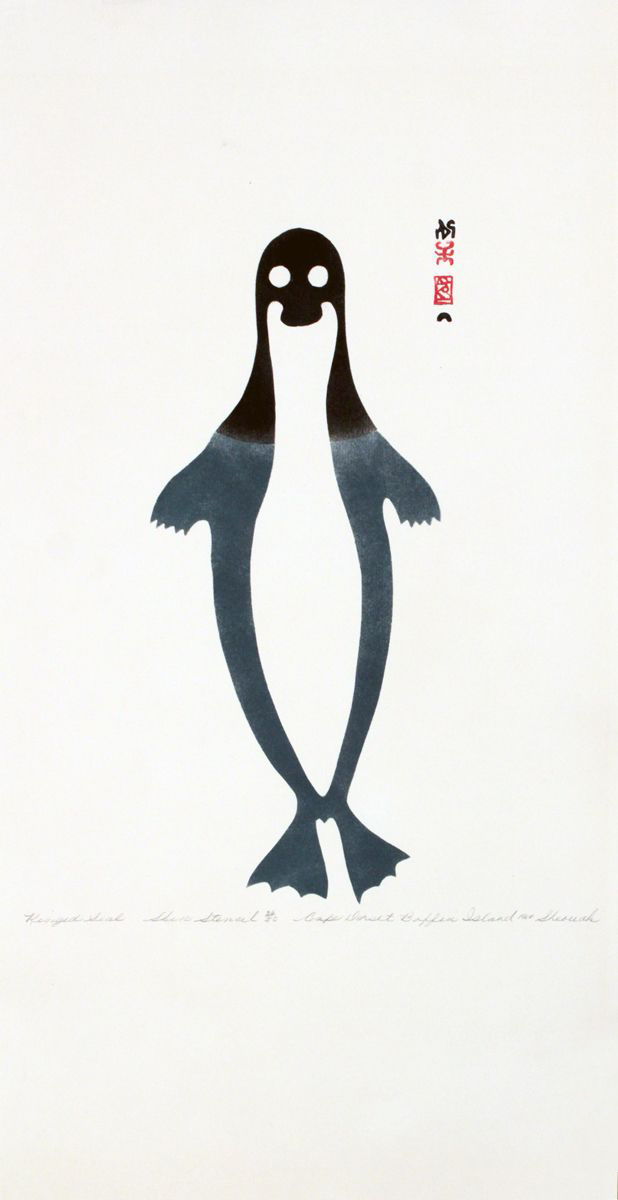

Sheouak, RINGED SEAL, 1960, Stencil, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 25 x 12 in.

Artists such as Paunichea and Sheouak are well represented in the Cape Dorset graphic collections. Despite their early success, these individuals are not as well known today. Some passed away before the end of the 1960s and others drifted away from the art programs over the years. Sheouak’s most famous graphic is the double figure symbol used by the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative to this day.

Qaunak Mikkigak, COMPOSITION (BIRD TRANSFORMATION), 1959, Pencil, 20 x 26 in.

Quanak Mikkigak, daughter of Mary Qayuaryuk, was originally a prolific graphic artist. Today, she is better known for her sculptures, like those of her niece, Oviloo Tunnillie. Qaunak’s graphics are filled with imaginative flights of fancy, fresh and immediate. Cape Dorset art from the 1960s includes rare examples of exploratory work in one medium by artists who went on to later fame for work in a completely different medium. Jamasie and Kiakshuk are artists best known for their graphics, who nevertheless carried the distinctiveness of their individual styles into the very few carvings they created.

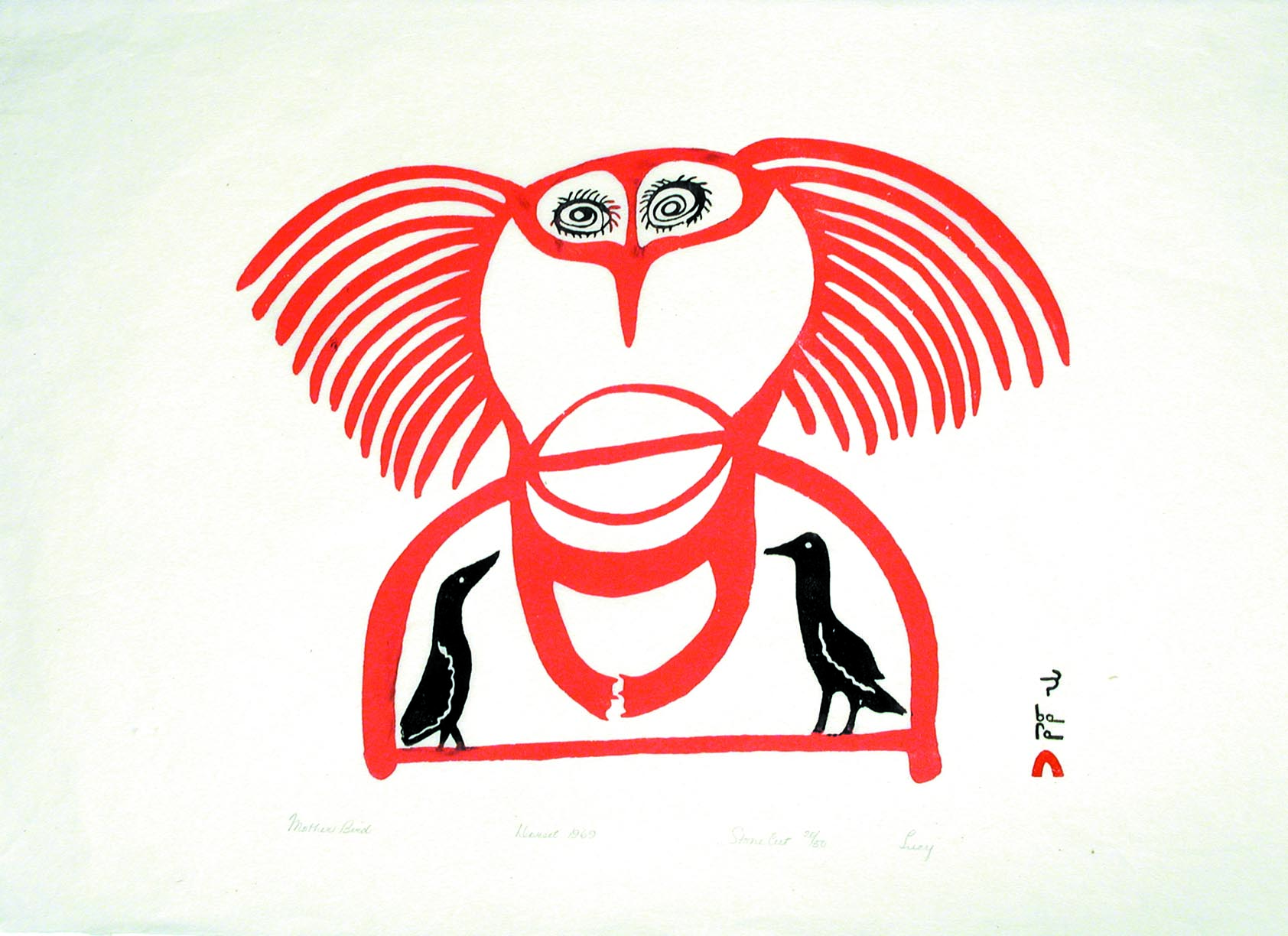

Lucy Qinnuayuak, MOTHER BIRD, 1970, Stonecut, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 18 x 24 in.

Some thoughts seem better suited to drawing, others to the three-dimensions of stone. Certain images seem to haunt the artist, emerging again an again, regardless of the medium chosen.

Pudlo Pudlat, BIRD, late 1960s, stone, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 9 1/2 x 14 x 4 1/2 in.

Pudlo is remembered for his imaginative graphics depicting flying forms hovering over northern landscapes. His carvings from the 1960s show his early fascination with flying birds and transforming spirits.

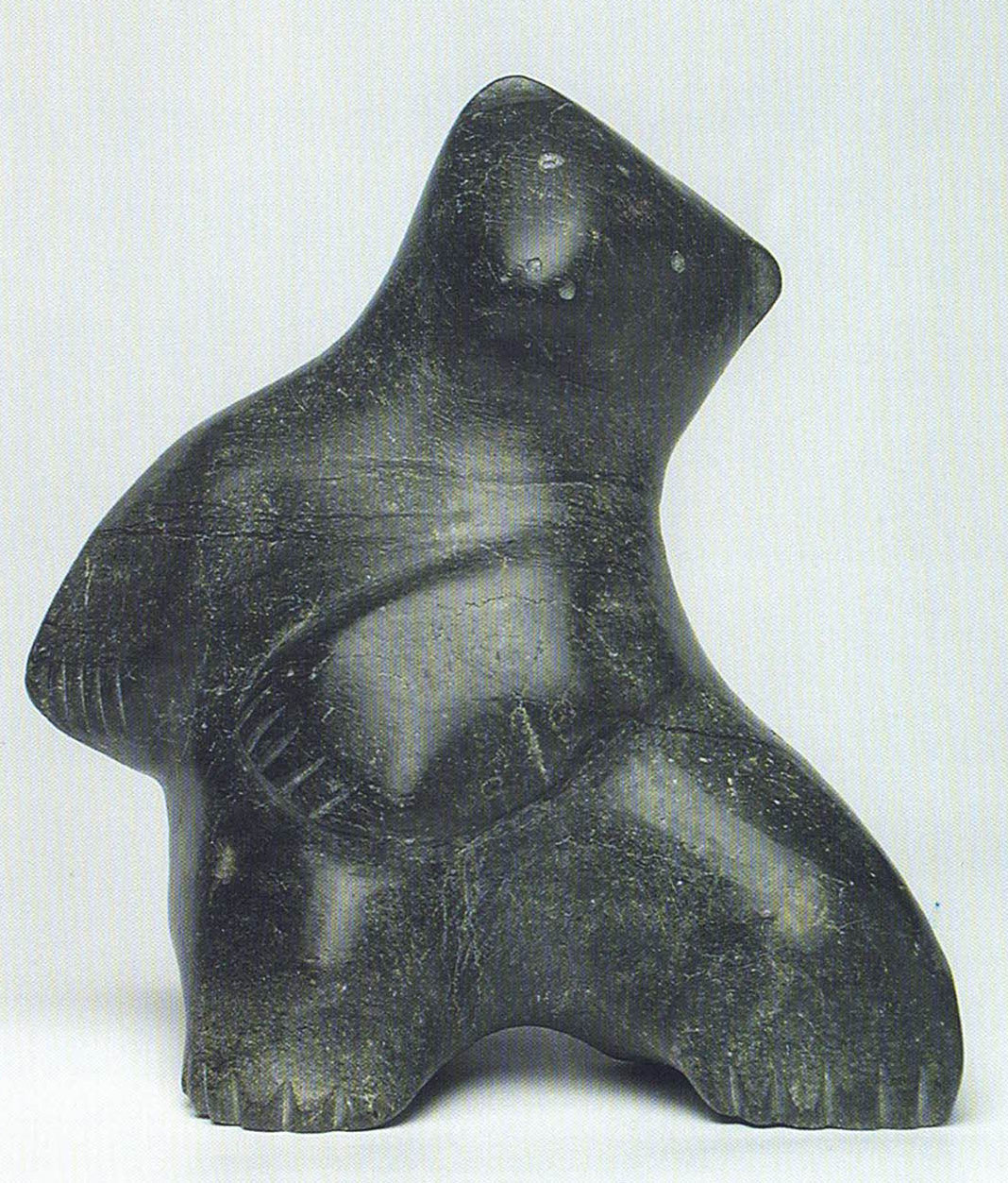

Pauta Saila, DANCING BEAR, ca. 1969, Stone, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 5 1/2 x 5 1/2 x 3 in.

Pauta Saila experimented liberally during the 1960s before settling on sculpture as his preferred medium. His distinctive images of bears have become hallmarks of contemporary Inuit art.

Kenojuak Ashevak, OWL SPIRIT, 1969, Stonecut, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 24 /12 x 34 in.

It is not overstatement to say that Kenojuak’s birds have become the international icons of Inuit art. Her mercurial rise to fame is a result of her confident, economical line and the comfort with which her imagery flows from drawing to engraving, to stonecut and even to stone.

Abraham Etungat, BIRD, 1969, Stone, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 3 x 2 1/2 x 1 in.

The carvers of the 1960s worked with rounded forms or sharp details, each developing an individual visual language. Works by many artists are instantly-recognizable and stand today as ‘signatures’ for all of Cape Dorset sculpture.

Sheokjuk Oqutaq, LOON, 1965, Stone, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 4 x 3 x 9 in.

Sheokjuk Oqutaq first worked at the Cape Dorset co-op as a carpenter. He had tried carving in ivory when he lived in Kimmirut during the 1950s, but he blossomed as a sculptor in Cape Dorset under the encouragement of Terry Ryan. Although he is now remembered for his break-taking, fragile carvings of loons, Sheokjuk explored other naturalistic subjects during the 1960s, including dogs and human figures.

Johnniebo Ashevak, MOONSPIRIT, 1963, Engraving, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 8 3/4 x 11 3/4 in.

Cross-influence is often evident between artists who worked closely together, such as husband and wife, or parent and child. Eleeshushe’s drawing reflects the appearance of her husband’s famous graphics. Anarnik had already been drawing for five years when her daughter, Ningeeuga, returned to Dorset after tuberculosis treatment in the south. Kenojuak and her husband, Johnniebo, play between them with form.

Pitseolak Ashoona, COMPOSITION (BIRD AND HUNTING IMPLEMENTS), ca.1968 Pentel, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 18 x 24 in.

As in so many of their drawings, interesting connections can be seen between the work of Pitseolak and her daughter, Napatchie.

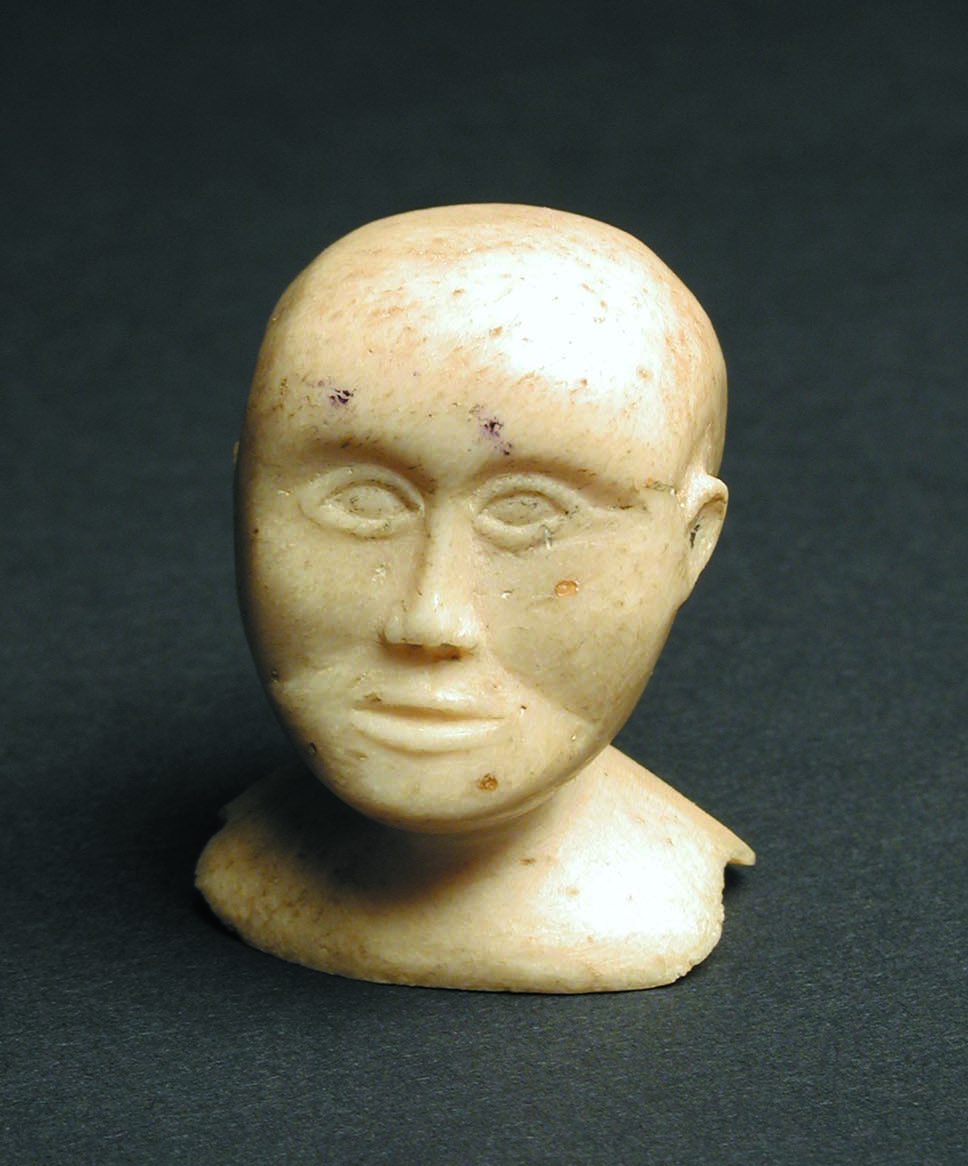

Saggiak, HEAD OF A DOLL, 1960s, Bone, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 2 x 2 x 1 1/2 in.

This father and son represent the dramatic changes that occurred in one generation during the 1960s. Saggiak lived most of his life on the land, while Kumakuluk lived from a young age in the settlement. Saggiak’s meticulous miniature work is reminiscent of the small portable traditions of Inuit carving. Kumakuluk’s larger sculpture still expresses something about the older way of life, but is couched in a modern, confident style.

Artist Unknown, FANTSTICAL ANIMAL, ca. 1964, Stone, Kinngait (Cape Dorset), 5 x 20 1/4 x 2 1/4 in.

Sculpture was often unsigned during the 1950s and 1960s. Some works can be identified by living artists; some may be attributed by comparison of stylistic details; others remain unknown at this time.