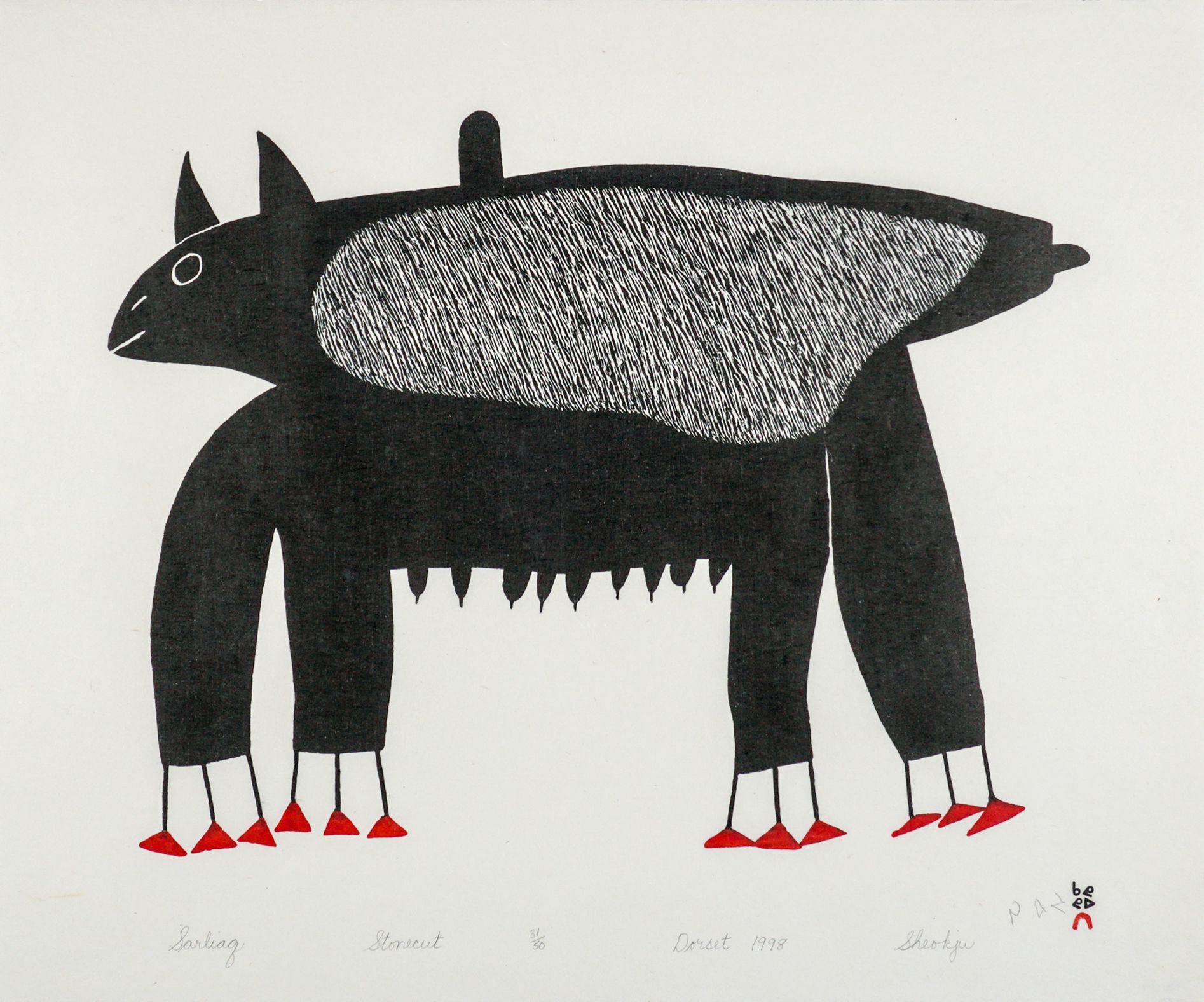

Sheojuk Etidlooie, Sarliaq (Female Dog), 1998, stonecut, edition of 50, 19 x 23 in.

“I started out drawing by accident at the Church Christmas games. That’s when I learned that I could draw, and ever since then I have gained confidence. I have to think about a drawing for a while before I start to make it. My drawings are from me, they are my own but it is not easy to make them. I am proud of the Dorset people who draw well.”

—Sheojuk Etidlooie [1]

Our perception of an artist is that technique can be learned but talent is latent, lying dormant until stirred by opportunity. Etidlooie’s opportunity came later in life. She did not begin to draw until she was in her mid-60s, in the early 1990s, as the result of a chance occurrence. Merely six months later, the first of her distinctive images appeared on the cover of the 1994 Cape Dorset annual graphics collection catalogue. Her career was short but prolific, lasting a few years until her sudden passing in 1999. Today, Etidlooie’s legacy lives on as one of the Kinngait Studios’ most distinctive graphic artists.

Who was Sheojuk Etidlooie?

Etidlooie was born in 1929 in Akkuatuloulavik, an outpost camp near Kinngait (Cape Dorset) on southern Baffin Island. Growing up in this environment gave her not only a knowledge of traditional life, but also a familiarity with the land, animals, and birds. She settled in Ikpiarjuk (Arctic Bay) with her husband and lived there for many years, eventually moving to Iqaluit. In the early 1990s, Etidlooie returned to Kinngait. She had always admired the artists there, especially those who could draw.

During the church Christmas games in 1993, Etidlooie drew a picture of a qulliq (seal oil lamp). This drawing won first prize, awarded by respected artists Kananginak and Paulassie Pootoogook. Encouraged by this success, and under the direction and support of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, Etidlooie began drawing regularly, gaining more confidence as the time passed. Her drawings were first made into prints in 1994 and were included in each spring and fall release until 1999. In 1998, almost half of the prints in the Cape Dorset annual graphics collection were hers, a remarkable success for an emerging artist.

Sheojuk Etidlooie, Uummiakuta (Long Boat), 1997, stonecut, edition of 50, 25 x 28 in.

A Distinctive Style

Etidlooie would explore themes by creating a series of drawings and finding various ways of presenting the same fundamental image. Perhaps an echo of her lifelong experience with sewing during which cut-outs would often be used, she worked frequently with tracings to transfer the outlines of her earlier drawings or prints onto paper. Each work was then given an entirely new character through colour variation, surface embellishment, and subtle modification of the original design.

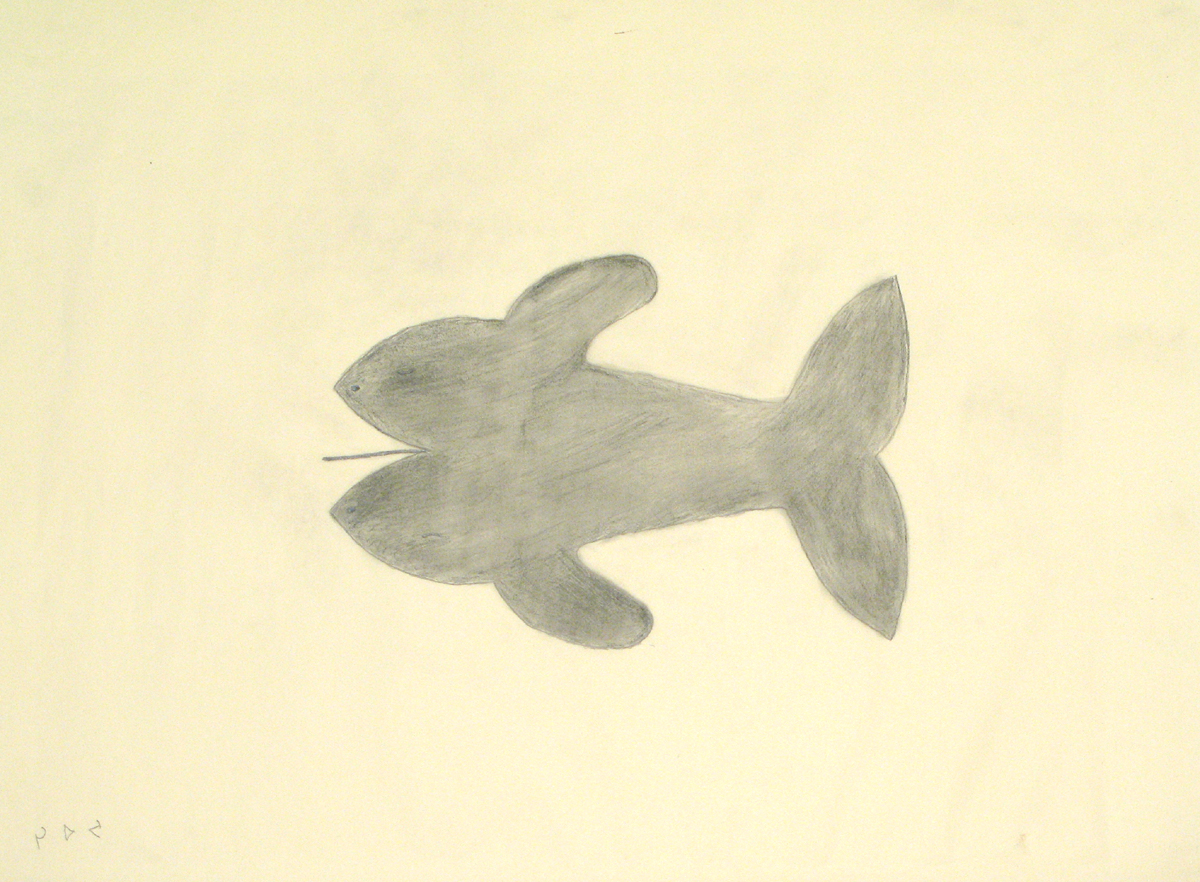

Studies of birds, through their translation into prints, became the most recognizable of Etidlooie’s recurring subjects. Her signature owl, presented single or in more complex compositions, was given individual personality through variations in colour and detail. Her birds with raised wings became wonderfully intriguing and contemporary images. For Etidlooie, form was flexible: a bird could be as ambiguous as a blob, as recognizable as a two-winged raven in flight, or somewhere precariously in-between.

Etidlooie’s unapologetic style indicated her confidence as an emerging artist and this allowed her to experiment with new media beyond drawing. Printer Paul Machnik introduced etching and aquatint to the Kinngait Studios in 1993, a medium through which Etidlooie’s images were propelled to a new dimension through colour luminosity and visual depth. But it wasn’t always easy. During etching workshops, Etidlooie’s abstracted images would attract whispers and giggles from others, which upset the artist but ultimately encouraged her to work harder. She migrated to a private room to work alone and there would produce several images per day, many of which would go on to become extraordinary prints. [2]

Sheojuk Etidlooie, Narwhal (Grey), 1995-96, graphite & coloured pencil, 20 x 26 in.

Etidlooie and Feheley

Etidlooie became known primarily for her prints, but nowhere was her genius more apparent than in her original drawings. In the summer of 1998 during a trip to Kinngait, Pat Feheley saw her original drawings for the first time. She and Etidlooie met and had several interviews about the artist’s work. During their conversations, Etidlooie shed light on the many near-abstract forms that defined her bold drawings, identifying them as birds, bears, boats, and even giants. These works culminated in Etidlooie’s first solo-exhibition held at Feheley Fine Arts in 1998, Sheojuk Etidlooie: Original Drawings. The titles and descriptions resulting from these conversations foregrounded Etidlooie’s voice and vision and brought her imagery to life.

The following spring, Pat travelled again to Kinngait to witness the dawn of Nunavut, which became an official territory on April 1, 1999. She met with Etidlooie to discuss a new selection of drawings for her next exhibition. Sadly, soon after, Etidlooie passed away. In the fall of 1999, Feheley Fine Arts held the posthumous exhibition Transformed: The Last Works of Sheojuk Etidlooie. Originally conceived as a second exhibition of new drawings by the artist, the show was presented as a memorial exhibition. It featured both early and recent works while also presenting, for the first time, a series of oil stick painting defined by colour and Etidlooie’s signature gestural strokes. These works, along with her later coloured pencil drawings and magnificent prints, ensured her standing not only as Kinngait’s break-out artist of the 1990s, but as one of the most brilliant of Inuit artists of her generation.

Parts of this blog post were adapted from the Feheley Fine Arts catalogues Sheojuk Etidlooie: Original Drawings(1998) [click here to view catalogue] and Transformed: The Last Works of Sheojuk Etidlooie (1999) [click here to view catalogue].

Sources:

[1] Sheojuk Etidlooie, interview with Pat Feheley, Kinngait, July 1998.

[2] Interview with Paul Machnik, 12 September 2020.