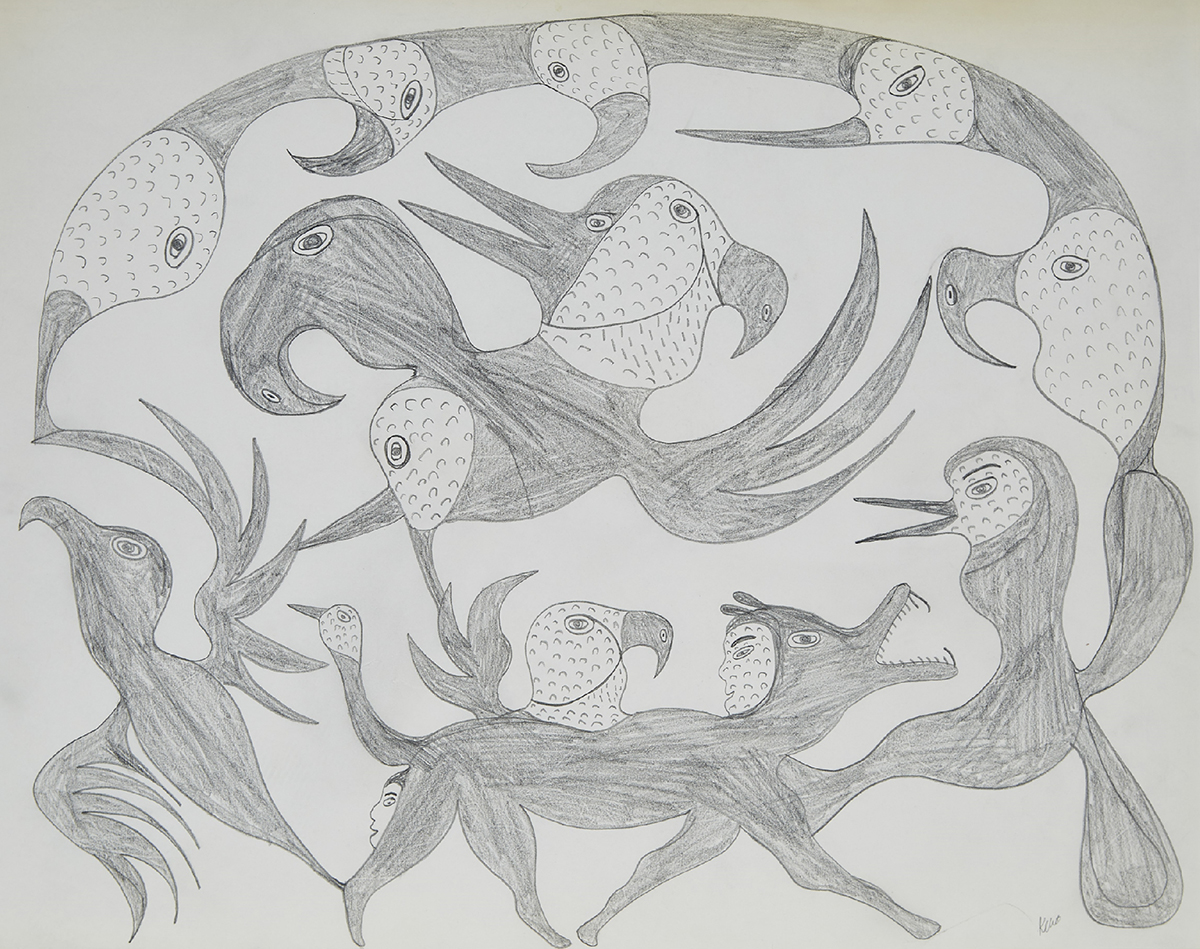

Kenojuak Ashevak, SPIRITS COMPOSITION, 1959, graphite, 18 3/4 x 24 in.

Exhibition opened October 12, 2019

In celebration of the Kinngait Studios’ 60th anniversary, this exhibition features an unbelievable collection of Cape Dorset prints—one from each year since the studios’ inception. The graphics chosen acknowledge the many artists who passed through the studios over six decades, highlighting their innovations in style, technique, scale, printmaking type, and subject matter.

Formally established in 1959, the studios have welcomed experimentation and innovation in printmaking for six decades. But the story started long before. Eight years earlier, Southern artist James Houston and his wife Alma were sent North by the Canadian government to establish an arts and crafts program in Kinngait. From there, the first printmaking experiments were initiated in 1957, followed by the first print shop in 1958, and finally, the inaugural print release in 1959.

The first print shop was small but mighty. At 512 square feet, the studio was referred to as sanaunguabik—a place to make small things. Today in 2019, things have changed: the print studios are now housed in the Kenojuak Cultural Centre, a 10,000 square foot space where community meetings and exhibitions are held. Along with larger facilities have come larger prints. For example, Ooloosie Saila’s Silaksiaq (Beautiful Day), 2019. The lithograph stands at nearly three times the size of Kenojuak Ashevak’s Rabbit Eating Seaweed, 1959, the legendary artist’s first-ever print. Technique and subject matter has similarly evolved over time. Ooloosie’s print is a lithograph, a technique introduced to the printshop in the 1970s. Rabbit Eating Seaweed was made with stencil, a printmaking method that was implemented by Houston in the early days still used today. While the two prints differ in many ways, they are linked by the thread of continued creativity from the Kinngait artists. From one generation to the next, artistic ambition remains consistent over six decades.

1950’s

The 1950’s marked the experimental days of the fledgling studios. First generation artists like Kenojuak Ashevak were making fantastically imaginative drawings that would later become the basis for stonecut prints. The first prints were linocuts and eventually evolved into the stonecut, a Kinngait adaptation of Japanese woodblock printing. The use of stone made sense: it was a sustainable and local natural resource which many artists were already familiar with carving. Artist Kananginak Pootoogook, who was central to the printshop’s foundation years and the Co-op’s inaugural president, described the process of making the first prints:

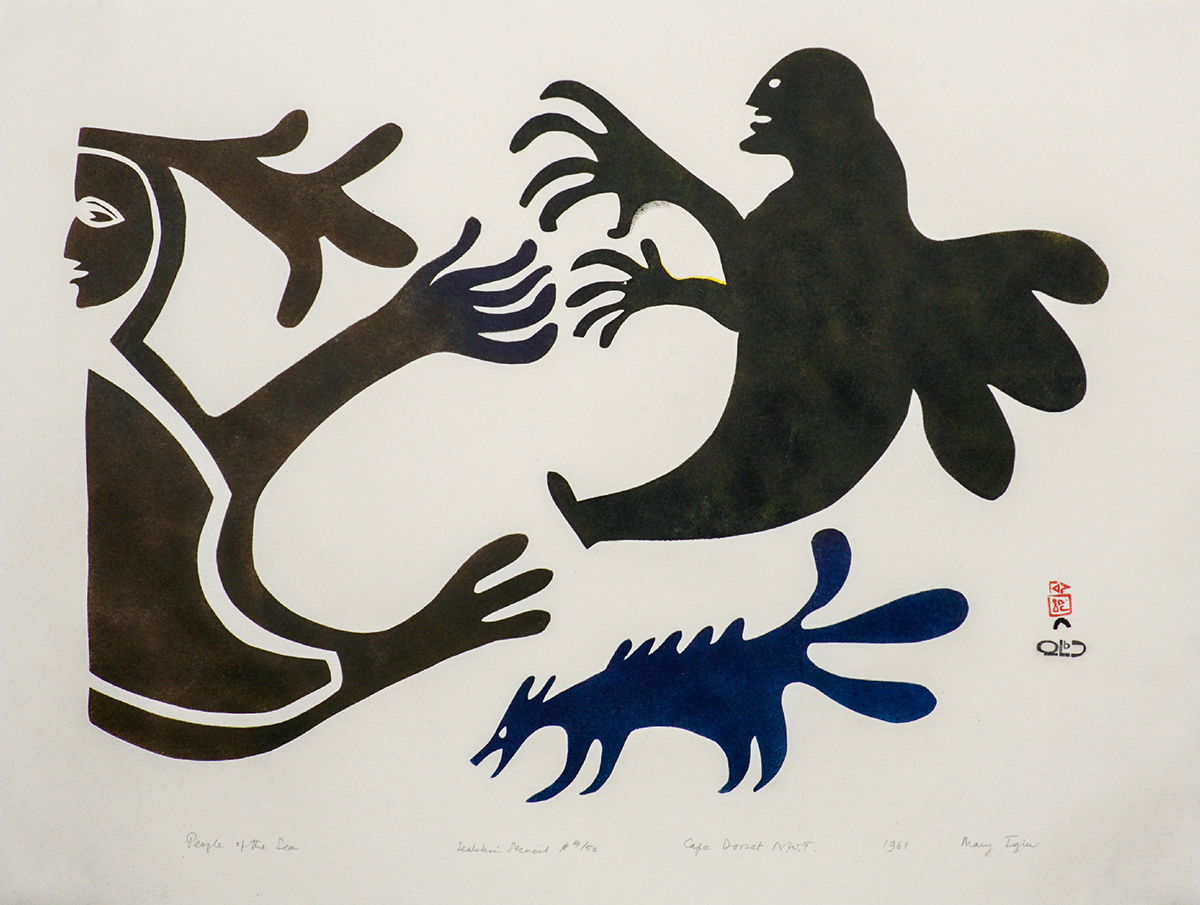

Mary Igiu, PEOPLE OF THE SEA, 1961, stencil, 18 1/2 x 24 in.

“We first tried printmaking by using linoleum which was stuck to a piece of thin wood and when the glue was dry we would copy the design onto the linoleum with tools. When the design was finished it was inked and then paper was laid on top. This was rubbed well with a small spoon, and when it was well impressed the paper was removed. If it was satisfactory we made twelve copies. […] We also tried using small pieces of soapstone to see if it was better than linoleum, and so we made our first prints on stone.” —Kananginak Pootoogook (Cape Dorset Print Catalogue, 1973)

1960’s

Terry Ryan joined the printshop in the summer of 1960 as Houston’s temporary assistant and was soon after hired as the studio’s first general manager. He introduced engraving and etching in “… an attempt to get them to omit the middle man,” as artists would be able to draw or etch directly on a plate rather than have original drawings pass through several hands during the stonecut process. In 1961, the first engraving was made by artist Kiakshuk. Stencil was also used frequently, as seen in Kiakshuk’s Ancient Meeting, 1960 and Mary Igiu’s People of the Sea, 1961. However, the claim that stencils were made from sealskin was later revealed as simply a marketing strategy to appeal to a Southern audience. In reality, the stencils were much more makeshift—made from Bristol board covered in melted wax.

1970’s–80’s

The 1970’s marked the introduction of lithography to the Kinngait Studios. Ryan acquired both lithography and Vandercook proofing presses from the South which made the heavy journey North to Kinngait’s new litho-shop. Several lithographers from the South made the trip to Kinngait to train a specialized team of printers. The studio also had a brief stint with typography and produced the superb publication The Inuit World, before closing-up the type shop for good. Lithography, however, remained and continued attract Southern artists. Names like Michael Snow, Joyce Wieland, Les Levine, Toni Onley, and William Kurelek travelled North for collaborations at the Kinngait studios. Toronto-based artist K.M. Graham facilitated experiments in acrylic painting which involved artists Lucy Qinnuayuaq, Pudlo Pudlat, and Kingmeata Etidlooie. These artists later incorporated the new technique of painting with a brush into their own prints. In the early 1980’s, Kimmirut-born Jimmy Manning joined the Kinngait Studios in as printshop manager and stayed for nearly three decades.

1990’s

The 1990’s started off with a bang: Pudlo Pudlat became the first Inuit artist to have a solo-exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada. In the North, printmaking innovation continued. Ryan invited Montreal printer Paul Machnik to the Kinngait Studios in 1994 to re-introduce etching to the artists. This time aquatint was involved incorporating vibrant washes of colour. Artist Mewa Armata facilitated oil stick drawing workshops during these years, a medium that combined the aesthetic of oil paint with the familiarity of a drawing stick. These new techniques of the 1990’s resonated particularly well with artist Sheojuk Etidloie whose etching and aquatints were featured prominently in the annual print collections between 1994–1999. The year 1999 also marked the formation of Nunavut as its own territory (formerly the Northwest Territories), and the establishment of an Inuit-led government. Kenojuak Ashevak’s monumental diptych Siilavut, Nunavut (Our Environment, Our Land), 1999 celebrates this important moment in Canadian history.

Ooloosie Saila, SILAKSIAQ (BEAUTIFUL DAY), 2019, lithograph, 30 x 43 3/4 in.

2000’s–2010’s

The millennium marked the rise of a new generation of artists: Shuvinai Ashoona, Annie Pootoogook, Itee Pootoogook, Tim Pitsiulak, and more. They began to see work that they started in the 1990’s come to fruition in the form of prints. Some Kinngait artists also began to travel internationally: Annie Pootoogook and Padloo Samayualie completed residencies at the Glenfiddich Distillery in Scotland and Brooklyn, New York, respectively. Tim Pitsiulak went South to learn silkscreen printing at Open Studio in Toronto. During this time he produced Swimming Bear, 2016, a rare and stunning silkscreen on black paper.

Eventually, drawing caught on, and for the first time since the mid-1950’s resurfaced as a popular medium at the Kinngait Studios. Annie Pootoogook won the Sobey Art Award in 2006, and her success encouraged more drawing experimentation at the studios. This reinvigorated elder artists. Ohotaq Mikkigak for example returned to the studios after an almost 40-year hiatus. He found inspiration in younger generation artists like Shuvinai Ashoona, who were working with coloured pencil on large scale paper. Other first generation artists, like Kenojuak Ashevak and Kananginak Pootoogook, continued to produce work until the very end of their lives. In accordance with the success of drawing, printmaking of all varieties has continued on into 2019 with Ningiukulu Teevee and Saimaiyu Akesuk noted as some of the studio’s most sought-after graphic artists to date.

Feheley Fine Arts is delighted to present this unique exhibition in celebration of 60 years of Kinngait printmaking.

Sources and further reading:

Feheley, Patricia. “Terry Ryan: A Visionary with a Pragmatic Edge Part One: Sketching a Future.” Inuit Art Quarterly 24.1 (Spring 2009): 10-19.

Feheley, Patricia. “Terry Ryan: A Visionary with a Pragmatic Edge Part Two: Hugging the Curving Shore.” Inuit Art Quarterly 24.2 (Summer 2009): 14-23.

The Cape Dorset Annual Print Catalogue (1973).

Ryan, Leslie Boyd. Cape Dorset Prints, A Retrospective: Fifty Years of Printmaking at the Kinngait Studios. San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2007.

To view available prints from Cape Dorset, click here.